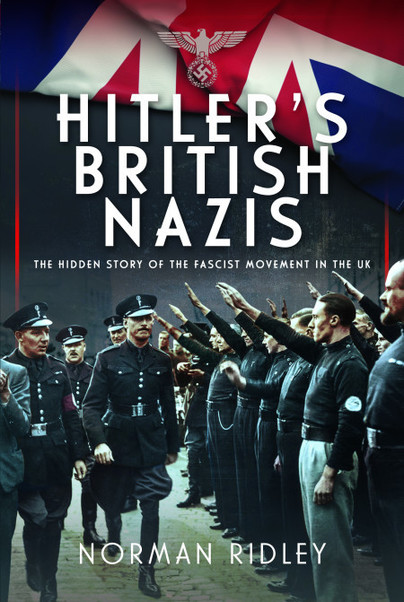

Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

The British Union of Fascists Rally at Olympia on 7 June 1934

The BUF rally held at Olympia in June 1934 was planned along the lines of Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies and Mosley set out to make it the largest, most spectacular public gathering in the history of British politics. Fifteen thousand gathered to hear Mosley speak including young men and women in evening dress, middle-class family parties with small children, and a large gathering of workers in their working clothes and, by some accounts, about 150 Members of Parliament. 2 The proceedings were carefully stage-managed on an impressively theatrical level but instead of swastikas there was a profusion of Blackshirt banners bearing the ‘bolt of lightning’ symbol and Union Jacks fluttered everywhere. It is clear that the communists made well-organized plans to assault fascists and break up the meeting while the fascists used excessive force in resisting this attack on one of their set-piece events.

Proceedings were delayed for about half an hour by violent protests outside the building but when Mosley eventually arrived the lights of the hall flickered, and a spotlight swung round from the platform to illuminate him arriving to a fanfare. Some people raised their arms in a fascist salute but above the cheers could be heard the unmistakable sound of booing. Flanked by his bodyguards and preceded by a procession of uniformed BUF members bearing fascist banners, Mosley walked down the central aisle of Olympia towards a raised platform at the end of the hall. Collin Brooks, the former editor of Rothermere’s Sunday Despatch reported that ‘searchlights were directed to the far end, the Blackshirts lined the centre corridor – and trumpets brayed as a great mass of Union Jacks surmounted by Roman plates passed towards the platform.’ Mosley gave the fascist salute and began to speak but the sound amplification system malfunctioned and his words were unintelligible. Immediately, a well-organised campaign of disruption began. Agitators shouted slogans leading to chaos in the hall. The Blackshirt stewards swiftly and brutally attacked the first hecklers. Despite the presence of a thousand police officers fights broke out all over the arena. For close to two hours the meeting dragged on like that, interruption following interruption and ejection. Outside the auditorium, 200 Blackshirts patrolled the corridors, beating up those already ejected from the main hall. Of the hundreds who suffered injuries, some fifty needed hospital treatment and five were detained there as a result of the beatings they received.

Mosley continued to speak even though nobody could make out what he was saying as the venue continue to empty. Outside, communists such as Phil Piratin were waiting to attack BUF supporters. ‘some of them paid for what they had done that night.’ 3 Then, inside the arena a voice sounded high up in the rafters saying `Down with Fascism!’ Balanced one hundred and fifty feet above the crowd, in a scene that would have graced any adventure cinema screening, a man was seen clambering across the girders pursued from each side by Blackshirts. All the men then were lost in the darkness and there came the sound of breaking glass. Chaos ensued.

Mosley was delighted with the reaction to Olympia. A Commons debate immediately after Olympia on 14 June saw eight of the fifteen government supporters who spoke defend the BUF’s actions and heaped blame for the riot on the communists who were acting against the interests of free speech and in any case, reports of violence had been greatly exaggerated. There was a widespread sympathy for Mosley in the ruling Conservative Party and a feeling that, on the economic front, he was offering to do what the government had promised but failed to deliver. He was in fact a convenient stick with which to beat Prime Minister Baldwin. When Sir Thomas Moore called for concord and agreement between the old historic Conservative Party and this ‘new virile offshoot’ he spoke for many and the events of Olympia did nothing to dampen their enthusiasm.

For the BUF, Olympia proved to be a catalyst for recruitment. There were queues outside its Chelsea headquarters as people of all classes waited to sign up as members but, in a worrying sign in terms of public safety, the communists saw a sudden rise in their membership also. Fortunately, there was no escalation in violence as BUF meetings continued to be held without disruption but that was not because the left retreated. Significantly, anti-fascist demonstrations deterred outdoor gatherings of the BUF and in some cases caused cancellation of rallies and indoor meetings were controlled by allocation of tickets and strict police controls.

Order your copy here.