Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

Fraser Barton ‘Barry’ Sutton D.F.C.

As deeper plunges the diver the less he sees

so the pilot climbing in the sky

becomes more enclosed in a dome of unreflecting light

the blue above becomes purple

then black, as sunlight fades

So wrote Fraser Barton ‘Barry’ Sutton some forty years after the end of the Second World War in which he flew, fought and was thrice posted ‘missing in action’. Having had strong Jersey connections all his life, he returned here in retirement and spent his last years living in The Boathouse on Rozel Harbour. He lies buried in Holy Trinity Churchyard.

The quotation above is from an extensive soliloquy in which he recalls those moments he experienced as a young man of 21, first in the chaos of the German attack on France in May 1940 and some few weeks later in the skies over England as Göring’s ‘Adlerangrif’ (Eagle Attack) was unleashed. None of it smacks of ego, of triumphalism or of heroism, all of which were anathema to him. It is a record of feelings seared into memory during moments of intense experiences where life hung by a thread.

Barry Sutton spent a peripatetic childhood. Born in Oxfordshire, he spent time with his grandfather in the pristine grandeur of the Canadian Rockies and then in Argentina where his father tried and failed to establish a ranching enterprise. At some point, his parents separated and his father must have settled in Jersey because he was living at Roslyn at La Rocque just prior to the occupation. Barry would have known the island well as a child although he was schooled in England and lived there with his grandmother.

As a young man he was fascinated by speed and owned an Ariel motorcycle which served him well after he left school and took employment as a reporter on the Nottingham Journal. That life, however, was never going to satisfy this man and when his journalistic enquiries revealed government plans to form a part-time volunteer reserve for the Air Force, he was immediately interested and, in 1937, applied for admission. He was accepted, much to his surprise, and learned to fly, at weekends, in a Tiger Moth bi-plane. After the Munich Crisis of September 1938, Barry decided that he would wait no more for a call-up and applied for a short service commission in the regular RAF, which at that time very much had an air of privilege and exclusiveness, somewhat akin to gentlemen’s clubs for well-connected young men of comfortable means. That all started to change the following year when the Auxiliary Air Force was formed which, by force of sheer necessity, prized ability and aptitude above social standing. Over half of all Battle of Britain pilots entered service through the AAF, all of whom were non-commissioned officers and carried the rank of Sergeant rather than Pilot Officer, the starting rank for officers.

Upon completion of training, Barry was posted to 56 Squadron, a Hurricane squadron at North Weald in Essex. The Hurricane was seen as the poor relation of the much-admired Spitfire but in fact it comprised two-thirds of Fighter Command strength and proved to be a more effective defence against Luftwaffe bombers while the Spitfires greater speed and manoeuvrability were employed against the fighter escorts. Barry was engaged to Sylvia on Christmas day 1939 and they married in February 1940.

When the Germans broke through the Meuse defences on the 10th of May 1940, throwing the French, Belgian and British forces into a desperate defensive frenzy, 56 Squadron was sent to Vitry-en-Artois to support ground troops, by now contemplating full retreat. As the lightning ‘Blitzkrieg’ German advance over-ran airfield after airfield, the squadron was forced, almost daily, to move its operations base. In the mayhem Pilot Officer Sutton, taking off to accompany bombers over Douai had his first brush with death. Out of nowhere, a German aircraft which he never saw put 100 shells through his airframe and one through his foot. He managed to land and immediately commandeered another Hurricane to re-join the fray. Taking of his shoe to examine his wound he found it was impossible to put it back on so he took off in his stocking feet. Upon landing a second time he realised that he needed medical attention and spent the next few days being shunted all over northern France prior to evacuation. He narrowly failed to get space on a hospital ship The Maid of Kent in Dieppe harbour and later, as he was being taken by train to Brest, heard that it had been blown to pieces by German bombs before it had even left the harbour.

Barry and Sylvia, who worked in a government department in Westminster, spent a few weeks together during his convalescence and Barry was fit for duty again by the end of July by which time the Luftwaffe offensive over Britain has started to intensify. He returned to North Weald where, during a frenzied four weeks the squadron lost a staggering eighteen aircraft with, thankfully, most pilots surviving by baling out before crashing. On the 12th of August, taking a German shell through his cooling system, Barry was forced to land at Manston with his windshield plastered with glycol coolant. He failed to see warning flags all over the airfield warning of craters (Manston had just experienced a devastating bombing attack) but somehow managed, inadvertently, to land on the only un-bombed strip of grass on the whole field. Barry claimed three enemy ‘kills’ during this time but on the 26th of August just before the squadron was withdrawn to Boscombe Down to recover, he became one of the above statistics when he fell victim to ‘friendly fire’ over the Thames Estuary. In the confusion of battle, a Spitfire, either by accident (there were a lot of shells flying about all over the place) or in a mistaken identity event, blew a hole in his fuel tank and set his Hurricane on fire. Barry baled out but suffered horrendous burns which kept him in hospital for a whole year.

Later in 1941, Barry was fit for action again. He was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and was posted to Burma where he took command of 135 Squadron in February 1942. Further postings took him to India where he gained further promotion to Squadron Leader in command of a Spitfire Wing. After the war he was awarded the D.F.C. (awarded to officer ranks for “an act or acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying in active operations against the enemy” and promoted again to Group Captain.

In his retirement years at Rozel with its tranquil setting and slow regular tidal rhythms, who can say what the memories of war must have meant to him with so many of his friends gone and so much endured. He loved to hear the sounds of the sea and listen his daughters read to him. One daughter described him as ‘a dreamy, diffident, funny man, floating rather than striding through life.’. Forty years of separation, however, had not dulled his memory of the time when he had, with others, remained resolute in the face of danger strapped into his aircraft taking off yet again and again to deal with fate described in his own words.

Behind this thundering blur of blades

Join living tissue, and all senses

To this puissant miracle;

Harness mind, hand and eye to its raging power.

Breathe its heady mist of hot oil, hot glycol,

The musty tang of those snarling pipes

Ranging the blunted snout.

Feel it trembling in gathering power

Through my feet and seat and spine,

Merging me into its deadliness.

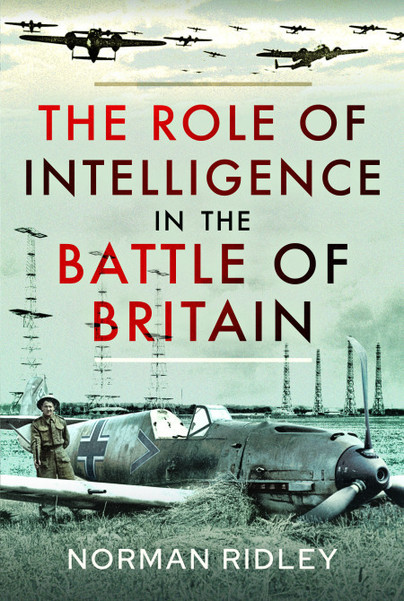

Order your copy here.