Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

Arno Breker 19 July 1900 – 13 February 1991

Arno Breker studied at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts and later went on to study and live in Paris, where he met artists such as Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso, and established a fine reputation for himself. The French classicist sculptor Aristide Maillot called Breker the German Michelangelo. He returned to live in Germany in 1932, having won a prize from the Prussian Ministry of Culture. Unfortunately, his work was not sufficiently Völkisch for Alfred Rosenberg, who railed against him in pages of the Völkischer Beobachter for his close association with the modernist Paul Klee, but Hitler approved of his work and so Rosenberg was obliged to mute his criticism. It was soon clear to Breker, however, that there were two distinct and opposite artistic movements vying for supremacy in Germany and with the rise to power of the Nazis he would, at some point, have to make a choice over which one he aligned with.

He had already been impressed with the politics of fascist Italy and had even been commissioned to restore Michelangelo’s marble sculpture Rondanini Pietà, which introduced him to the monumental imperial style.1 It was no surprise then that he now began to be drawn to Hitler’s style of leadership and began to align his aesthetic along the lines adopted by the Nazis. In George Kolbe’s opinion, there had been a noticeable change in Breker’s artistic viewpoint, causing him to discard earlier French influences and fall under the influence of the Nazis.

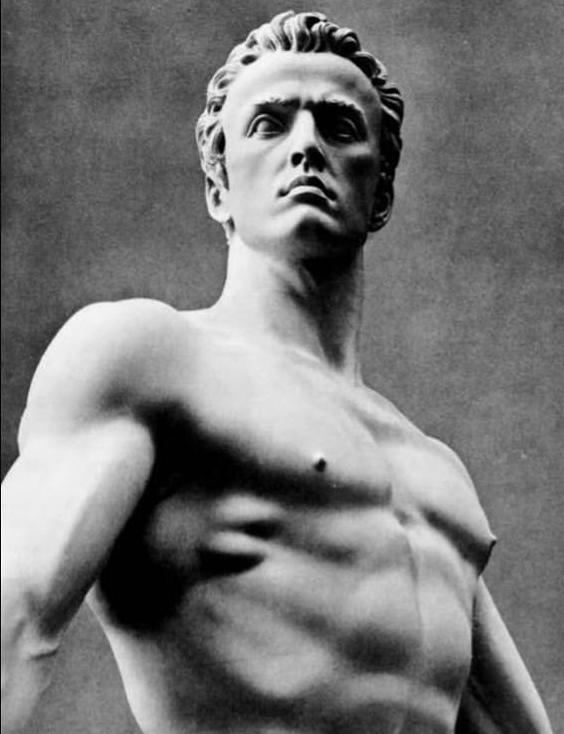

He became what the art expert Victor Dirksen called ‘a state sculptor’ but it was hard to know if it was expediency or political sympathy that caused his change of heart.2 What is clear is that he abandoned any modernist influences and from here on focused entirely on Classicism. He spoke of ‘massive figures built upon timeless Hellenic precedents [that] would define the aesthetic idiom both domestically and abroad’,3 but he was not averse to incorporating into his work ‘frequent political allegory to suit the taste of the regime’.4 His work belonged to a nineteenth-century tradition of ‘decent and respectable’ male nudity as a symbol of a young healthy nation imbued with moral strength and purity.5 It portrayed not sexual passion but a sublimated chaste virility showing male bonding in activities such as sport. The power of Aryan masculinity is channelled into a sense of dominant guardianship of the state. Sculptures by Breker and his fellow German sculptor Josef Thorak depict ‘musclemen of iron with grim expressions’ as examples of the new style of monumentalism which characterised the Nazi cultural programme. This programme, in turn, was an essential component of the Nazi political message which Alfred Rosenberg, reflecting the ideological framework in which such art works were interpreted, described as ‘the force and willpower’ of the age.6 Breker’s works came to occupy a position of particular propagandistic importance in the cultural programme of the Nazis.

When Breker won second prize in the sculpture competition held for the 1936 Olympics, Speer took note and commissioned him to create works for the Zeppelinfield in Nuremberg and the Arch of Triumph in Berlin. The first Führer commissions were at the end of 1937 for two monumental bronze sculptures, which Breker called Torch Bearer and Sword Bearer. Breker himself discussed his motivations in the design of such sculptures:

I have chosen the two pillars upon which each state is built, the man of the spirit represented by the torch, and the defender of the Reich by the man with the sword.7

Hitler called these images cast in stone with profiles, torsos and legs of the race’s greatest specimens ‘amongst the most beautiful ever created in Germany’ and had them moved to take up permanent residence on the front I of the New Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery) where he took it upon himself to rename the figures ‘The Party’ and ‘Wehrmacht’.

An essential feature of Breker’s Torch Bearer was the torch itself calling on the myth of Prometheus, the Titan god of fire. For the Nazis this symbolised the light they were bringing to lead the people out of darkness. It had been Goethe who, in his poem about Prometheus, had celebrated the courage of a man who had become the master of his own destiny after rebelling against the gods. It is hardly a coincidence that such an emphasis had been placed on the Olympic torch when its long journey from Olympia had been made such a feature of the 1936 games. The Nazi penchant for torchlit parades fits neatly into the symbolism of Prometheus also. The people were left to make the obvious connection.

Breker had modified his style to produce stilted and brutish caricatures of virility: steel-like bodies that owed everything to size and exaggeration and were simply perversions of the classical ideal.9 No other artist in the Third Reich would go on to play such an important role in the politico-cultural life of Nazi Germany, or receive so many prestigious commissions, and Breker would become a wealthy man as a result. Many of his later wartime sculptures were a celebration of warfare itself, as in Readiness, a 1939-sculpture with a clearly military propagandistic message of a man, with his sword half-drawn, ready for battle, a symbolic call to arms for the German people. In the famous photographs of Hitler in Paris in 1940, with the Eiffel Tower in the background, it is Speer and Breker who stand on either side of him.

Order your copy here.