Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

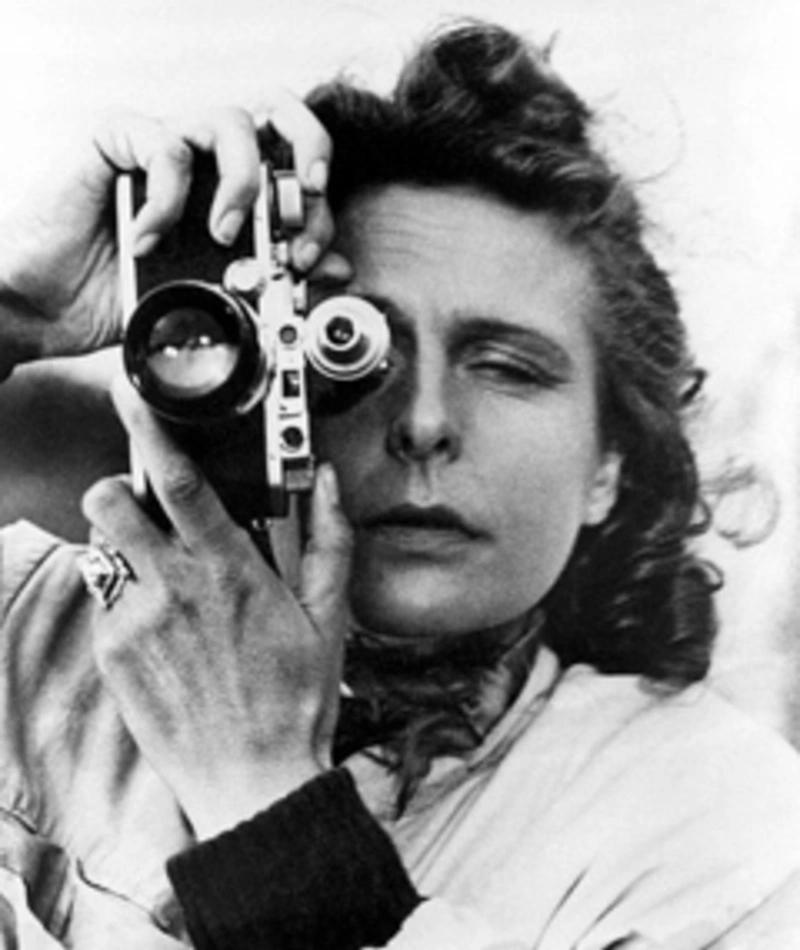

Leni Riefenstahl

Helene Amalie Bertha Riefenstahl was born in Berlin on 22 August 1902. She was a strong-featured attractive child with all the characteristics that would later see her take to the screen as an accomplished actor, but before that she trained as a ballet dancer. It was while dancing on stage that she first came to the attention of the film producer Arnold Fanck who was famous for his stunning filming of alpine landscapes. Leni acted in several of his films shot on location, becoming an accomplished climber and skier in the process. Not without mishap, however, as she fractured an ankle on her first outing on skis, but it never discouraged her or subsequently slowed her down.

The first film they made together was Der Helige Berg (The Holy Mountain), which came out in 1926. It involved a good deal of dancing for her, but it was not long before the lure of the silver screen had driven all thoughts of a dancing career from her mind. All this filming in the mountains gave Riefenstahl a deep love of the heroic ideal. These tough fit mountain climbers fascinated her and she, even then, began to dream of making films that captured the way she felt about them. Just like Fanck’s films they would capture all the majesty of the scenery and show how German life was deeply bonded to its environment. She would go on to make a total of six films for Fanck.

Riefenstahl had now turned into what David Gunston called ‘a highly attractive, vigorous and determined girl’ and still only 17. She could ski and climb with the best of them, but she did not lose her ‘essential femininity’. With each film she made she grew in confidence and became something of a star. A review in Close Up magazine called her ‘unexpectedly fresh, unexpectedly charming [she had] a flowing free rhythm, breath-catching beauty [which was] not blatant or manufactured but sensed with authenticity’. Then, with the advent of talkies, came the acid test for silent screen performers, but she passed with flying colours proving to have a voice of ‘pleasant well-modulate timbre [which] recorded satisfactorily’. However, acting was not that important to her. Although she was a famous actor with a burgeoning reputation, she was becoming increasingly possessed with a desire to produce and direct her own films. It was what she called her ‘passion’.

In 1931, she set up her own film production company and began work on a film, Das Blaue Licht (The Blue Light) in the spectacularly beautiful scenery of the Sarntal valley in the Italian Dolomites. As well as directing the film, she also starred in it, but the film was a disappointment. Critics slammed it for its ‘phony romanticism’ and Riefenstahl hit back at critics with anti-Semitic venom by saying’ ‘As long as the Jews are film critics, I’ll never have a success. But watch out, when Hitler takes the rudder, everything will change.’

Its weak story line was not helped by poor sound recording, but the scenery gave it ‘powerful atmospheric impact’ and is still seen by many as a film of ‘extraordinary beauty’.

Riefenstahl first saw Hitler at a rally in the Berlin Sportspalast on 27 February 1932. Her account of how she reacted at that time is significant in light of how she filmed him later. Upon hearing Hitler speak she would say that ‘It was like being struck by lightning…I felt quite paralysed’, which is the sort of reaction one associates with evangelical religious fervour. Much of Hitler’s reputation as an orator stems from Riefenstahl’s images of him, which undoubtedly were hugely influenced by her own emotional responses. She was moved to write to Hitler and was surprised to receive a reply within days from his adjutant Wilhelm Brückner.

Hitler had seen her in Das Blaue Licht and invited her to meet him at the North Sea fishing village of Horumersiel near Wilhelmhaven. She was already under his spell, urging all her friends to read Mein Kampf. ‘You’ll see,’ she told them ‘This is the coming man.’ When they met, she found Hitler ‘unexpectedly modest…like a completely normal person’. He told her that he had been impressed both with the film and with her role in it. Then a few weeks later, Hitler’s friend Ernst Hanfstängl was trying to find female company for Hitler that would ‘tame him and make him more human and approachable’ and took Riefenstahl to the Goebbels’ apartment for dinner, where Hitler was also a guest. Both Hitler and Goebbels were big film enthusiasts so there would have been much to talk about. They obviously all got on well because after dinner they went to Riefenstahl’s studio, where Hitler and Riefenstahl were politely left together to get to know each other. Hanfstängl recalls that Riefenstahl was ‘giving him the works’ by dancing in front of him and generally flirting with him. Hitler was extremely nervous and avoided eye contact, choosing to look at her books rather than her. Nevertheless, Hanfstängl, and Goebbels and his wife made their excuses and left. When asked two days later what had happened after that, Riefenstahl shrugged her shoulders in a hopeless gesture. She had made her mark, however, and when Hitler came to power the following year, Riefenstahl became his first-choice film maker for the Nazi Party, and they spent a great deal of time together at all of Hitler’s various houses. Although there is no evidence that she became his mistress, indeed Hanfstängl was of the opinion that Hitler was impotent or homosexual, Riefenstahl did not discourage the rumour. Her perceived closeness to the Führer was something she would exploit to gain a great deal of cooperation when making films for the Reich. Hitler grew very fond of Riefenstahl and called her his ‘perfect German woman’. They were seen together more and more at social functions and were frequent guests at the Goebbels’ apartment. ‘He respected me as an artist, nothing more,’ Riefenstahl would later write.

Goebbels and Riefenstahl had a mutual dislike for each other, but she became a close friend of his wife, Magda. Riefenstahl was now closely involved with Goebbels’ Short and Propaganda film section of his ministry and so could not avoid contact with him, despite his persistent unwanted sexual advances towards her. Thanks to Goebbels, the unspoken but persistent rumour that Riefenstahl was actually Jewish would be kept simmering away in the background. They were seen walking arm in arm at times especially during the 1938 Venice Film Festival but even then she confided to a newspaper that ‘the cripple Goebbels’ was ‘a big enemy of mine’. Goebbels had suggested in 1933 that she make a film of Hitler after coming to the conclusion that, despite personal animosities, she was the only German film-maker who understood what the Nazis were all about. Riefenstahl imagined a film in which she would show ‘the bond between the Führer and the people’. The problem for Goebbels was that Arnold Raether and Eberhard Fangauf, who had been responsible for filming party rallies since 1927, had been appointed to head the film division of his Propaganda Ministry, but it was Hitler personally who finally chose Riefenstahl to film the 1933 rally.

There was potential for a serious turf war between Goebbels’ people and Riefenstahl when they arrived at Nuremberg days before filming, but Riefenstahl had the good fortune to meet Speer who had been commissioned as ‘chief designer’ of the rally. Speer’s contribution to Riefenstahl’s film of the event, Der Sieg des Glaubens (Victory of the Faith) cannot be overstated. It was he who organised the mass marches and torchlit parades. It was his grandiose motifs that dominated the arena. He created the camera positions for her. By placing Hitler on a high platform, it made the choice of filming him from below an obvious one, reminiscent of the way that Fanck had filmed the climbers in his alpine epics. Together they worked out frames, angles and lighting.

Riefenstahl’s presence at the rally was deeply resented by Raether and Fangauf, who tried to undermine her with rumours of her alleged Jewishness and her alleged promiscuity. She was only there because of sexual favours to Nazi bigwigs, even Hitler himself, they whispered, but Speer, who was rapidly becoming a force to be reckoned with in the party, protected her even against Hess. She was clearly indebted to Speer but would later argue bitterly against his assertions that many of the ideas about camera angles and backgrounds had been prompted by him.

It was common for Reifenstahl to suffer a nervous collapse after shooting a major film. The strength and stamina that possessed her when she was in the mountains seemed to desert her on such occasions. Even Hitler worried that she took her work too seriously and gave too much but she ‘wore her breakdowns as a badge of honour’ casting her work in a heroic mould.

Order your copy here.