Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

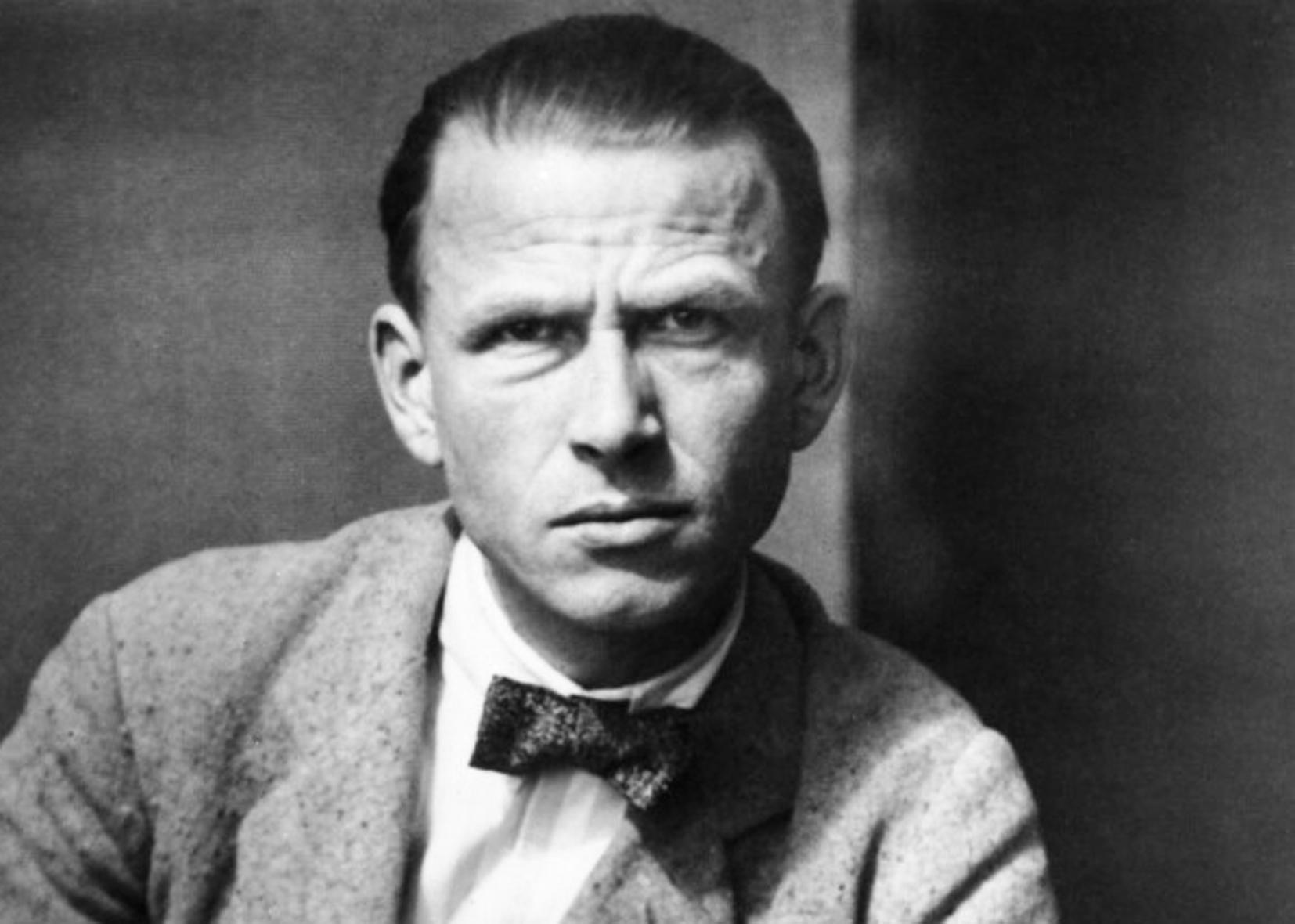

Otto Dix (2 December 1891 – 25 July 1969)

As a young man Otto Dix joined the Dresden School of Arts where he studied painting. When he went to war in 1914, he recalled that he saw it as an experience to ‘see everything with my own eyes [and] experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths for life for myself’. Dix was wounded several times during the war and almost died when a shrapnel splinter hit him in the neck. His experiences on the front line had a dramatic impact on his art, and he later recalled that ‘War is so bestial: hunger, lice, mud, those insane noises’. After the war, Dix said that he had recurring nightmares and his paintings and drawings became increasingly political as he tried to recreate his experiences through his art. His anger at the way war wounded were treated in Weimar Germany was most glaringly illustrated in The Skat Players, which depicted card-playing cripples, scarcely human with arms, legs, jaws, ears and noses shot away.

Dix was an Expressionist who had crossed over to Neue Sachlichkeit with its sharply focused verisimilitude, which resembled photography in its detail. Dix exhibited alongside Grosz, Hertfield and Raoul Hausmann in the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in Otto Burchard’s Berlin gallery in 1920, but his deeply disturbing graphic depictions, some of Western art’s most haunting portrayals of the violence and destruction, created such a public outcry that museums were forbidden to purchase or display them. Although very much a left-wing sympathiser, Dix refused to join the German Communist Party when urged to do so by his artist friends, saying that he preferred to stay out of ‘stupid politics’.

In 1927, he was given a professorship at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts and began a programme of recording life in Weimar society in his paintings, but then returned to the subject of war because he could see that people were starting to forget its horrors and suffering and thought only in terms of heroism and duty. In his painting Trench Warfare, he employed the religious triptych style that had been popular in medieval times to make altarpieces. Trouble was brewing for Dix, however, after the Nazis in Saxony called his paintings ‘vulgarities of the lowest taste’.

When most of his artistic friends fled Germany, Dix, who had never been openly critical of Hitler, thought he would be safe, but he might have known what was in store for him when, in April 1933, he had been forced out of his teaching role and then, a year later, was excluded from exhibitions. He had still been able to make a living by selling paintings to sympathetic individuals and institutions, but when Goebbels started his crusade against ‘degenerate art’ in 1936, 260 of Dix’s works were confiscated for mocking the German idea of heroism by depicting soldiers as idiots, sexual degenerates and drunkards. Dix’s refusal to join the NSDAP on the grounds that he was apolitical had to be reversed when membership was required as an essential prerequisite to joining the Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste. In order to be allowed to continue painting, he was made to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits.

In autumn 1939, Dix was arrested and charged with involvement in the Georg Esler plot on Hitler’s life that had taken place in Munich that November, but he was released when it became obvious that Elser had acted alone. During the Second World War, he joined the army and was eventually taken prisoner by the French in 1945.

Order your copy here.