Author Guest Post: Nigel Spooner

By Nigel Spooner, author of A History of Aviation at Brooklands in 100 Objects, published by Air World on 28 August 2024.

Mention the name ‘Brooklands’ to most people and you will either get a blank look or at best a recollection of it being something to do with motor racing. Very few will respond with knowledge of its more than 80 years of innovative contribution to 20th century aviation development. The world’s first custom-built motor racing circuit, which was constructed in the grounds of the Brooklands House estate in Weybridge, Surrey, would eventually become the site of one of Europe’s largest aircraft factories, employing around 14,000 people at its peak. By the time it finally closed in 1989, an estimated 18,564 aircraft of 258 types had been built, assembled or first flown at Brooklands.

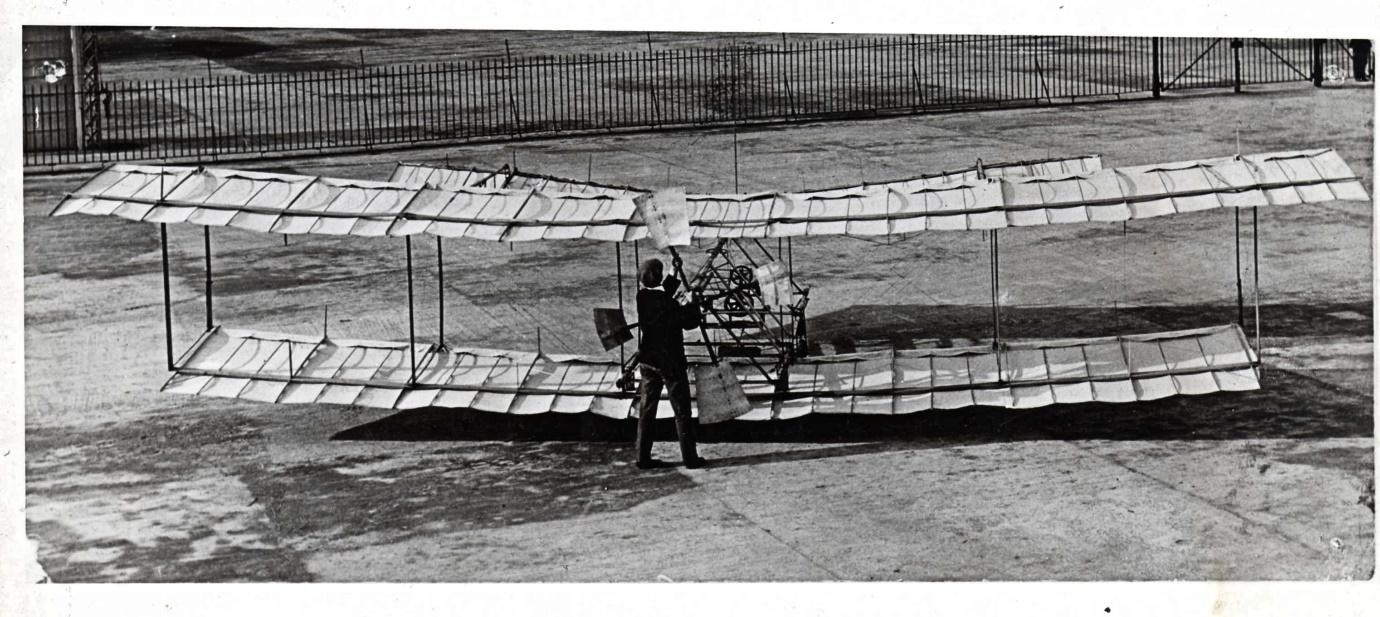

The first pioneer aviator to see the advantages of the Brooklands site was Alliott Verdon Roe, who undertook flight trials on the racetrack with his first biplane prior to founding his eponymous Avro aircraft company. Others, including Tom Sopwith and his chief pilot Harry Hawker, soon followed, establishing a rapidly growing ‘Flying Village’ in the wide space within the oval 2.8 mile (4.5km) racing circuit. The First World War brought closure to motor racing; the site was taken over by the Royal Flying Corps for the ongoing production of military aircraft by Sopwith, Vickers and others. A significant triumph was the construction of the modified Vickers Vimy bomber which was the first aircraft to fly non-stop across the Atlantic ocean, in 1919. By the end of the war the Flying Village had supplemented its early sheds with larger hangars; these supported a thriving aerodrome throughout the 1920s and 30s, offering pleasure flying and training alongside aircraft manufacturing. As the war clouds once again gathered over Europe, Brooklands witnessed the first flights of two aircraft that were so vital to the Royal Air Force in the Second World War: the Vickers Wellington bomber and Hawker Hurricane fighter.

In September 1939 all motor racing ceased once more at Brooklands; it was destined never to return. The entire site was given over to aircraft production, with new hangars constructed on sections of the racetrack. A devastating raid by the Luftwaffe in September 1940 resulted in the subsequent dispersal of several Brooklands departments to alternative facilities nearby, including the design section that developed Dr Barnes Wallis’s ‘bouncing bombs’ deployed in the dams raid on Germany in May 1943. By the time the conflict ended in 1945 it was clear that it would take a huge amount of money to return the track to racing; instead Vickers-Armstrongs acquired the site outright and proceeded to develop it for the production of its post-war civil and military aircraft.

Brooklands had been the site of secret wartime testing of Frank Whittle’s early jet engines in the back of converted Wellington bombers. It was also where, in the late 1940s, Vickers developed the Viscount airliner; it was not only the first aircraft powered by the new gas-turbine engines to carry fare-paying passengers, but also the first British airliner to achieve commercial success in North America. In the 1950s the same team, led by chief designer George Edwards, produced the Valiant, the country’s first jet-powered V-bomber. They followed it with the Vanguard and VC10 airliners, neither of which achieved the sales success of the Viscount. With the government’s cancellation, in 1965, of the advanced TSR2 strike aircraft just six months after its first flight, the by-then Sir George Edwards committed what had become the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) at Brooklands to collaborative projects with other countries. He also transferred some production of the commercially successful BAC One-Eleven twin jet airliner that was being built at Hurn, near Bournemouth; it would be the last complete aircraft to be produced at Brooklands.

The collaborations culminated in the Anglo-French Concorde supersonic transport. The largest proportion of Concorde construction was undertaken at Brooklands, with the sections being transported to Bristol or Toulouse for final assembly and flight testing. By then it was clear that the site, constrained by surrounding suburban housing and with its very short runway, was being eclipsed by larger facilities elsewhere. A final major triumph there for what had become British Aerospace was the design and initial manufacture of the wings of the Airbus A320 series. In 2019 the A320 overtook the Boeing 737 as the world’s best-selling airliner, with more than 18,000 sold to date, most of which still carry the spirit of Brooklands around the world.

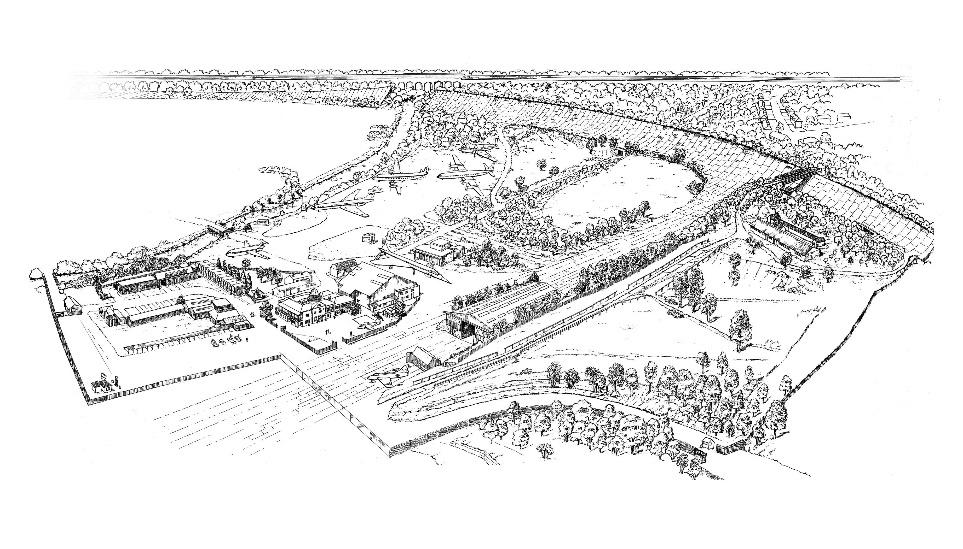

At the end of 1989 the aircraft factory closed for good, by which time much of the site had been sold for industrial development. Fortunately, a small area had been saved for the purposes of establishing a museum to celebrate the Brooklands achievements, both on the track and in the air. It opened in 1991 and has been growing ever since. I joined it as a volunteer steward when I retired in 2015 and spent my first few years learning just what an extraordinary place it was and is. My book came about from a desire to present the history of the aviation side of Brooklands by focusing on the stories behind various objects, large and small, that feature either in Brooklands Museum or others around the country. Many of the 100 objects that I chose are inevitably large and obvious, in the form of the many aircraft for which the site is famous. Others, though significant, are small and unexpected. They include a tool chest made by a teenage Vickers apprentice in the 1920s who went on to become a champion air racer and head of a major British airline.

There are the flying gloves made of beaver fur that belonged to the first woman to gain a pilot’s licence in the UK. And there is also the original propeller from the Vickers Vimy that was first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic. Finally, I occasionally cheated somewhat by choosing parts of a larger object on which to focus. My favourite example is the slight droop on the leading edge of the Concorde’s ogival delta wing. It is so subtle, but it was fundamental to the ability of the aircraft to fly slowly enough to be able to land at airports designed for subsonic aircraft. It was invented by a brilliant but very modest mathematician and aerodynamicist called Johanna Weber, who moved from her native Germany to work at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough after the war. She also played a major role in the development of Airbus wings – just one of the many extraordinary people who helped Brooklands earn its unique place in the annals of world aviation history.

Order your copy here.