Author Guest Post: Michael Pearson – The Ohio & Malta

MALTA

George Cross Island

‘Sleeping or waking Malta is always in my thoughts’, so said Admiral Lord Nelson during the Napoleonic Wars. With the rise of the Nazis in 1930’s Germany, and the increasing prospect that Europe would again plummet into war, Malta was once more destined to become vital to Allied interests.

As the 1930’s drew to a close and war loomed large on the horizon, Malta may have seemed relatively unimportant, as between the wars British and French naval planners decreed that the large modern French fleet would assume responsibility for the Mediterranean, its bases in North Africa making Malta of limited strategic importance. This proved to be a serious miscalculation, leading to limited upgrading of the island airfields and defences. The French armistice with Germany in June 1940 turned all previous calculations on their head, and Malta once again became the epicentre of military conflict in the Mediterranean, when Italy, with its sizeable modern navy, signed the Axis Tripartite pact with Germany and Japan.

The Royal Navy had a difficult enough job even before the armistice, being responsible for keeping German U-Boats and surface raiders from decimating vital convoys across the Atlantic, and defending trade routes to the Far East. Now it also needed to keep open sea lanes through the Mediterranean to Suez. To add to the problems, not only would the French Navy not be available to assist, it might actually defect to the enemy.

The armistice and Italy’s entry into the war meant that from French Tunisia to Italian Libya, there were no North African bases open to the Royal Navy. As a consequence, from Gibraltar at the tip of Spain to Alexandria in British occupied Egypt, a distance of some 2000 miles, the only friendly port of call was tiny Malta, approximately half way between the two and dangerously close to Italy.

In the period leading up to, and in the opening phases of the war, the British Army was markedly reluctant to contemplate the reinforcement of Malta. Initially this stance seemed justified when Italy attempted an invasion of Egypt from Libya. British and Commonwealth forces under General O’Connor pushed the numerically vastly superior invaders back so far that their complete expulsion from Libya seemed entirely feasible. Unfortunately, a political decision to remove much of O’Connor’s force to bolster the campaign in Greece coincided with the arrival in North Africa of Hitler’s response to the Italian setback – the newly formed well equipped Afrika Korps, led by the charismatic and highly capable General Erwin Rommel. In short order Rommel pushed the British and Commonwealth forces back to Egypt from where they had started, setting the tone for the coming three years of war in the desert, the pendulum swinging first one way then the other.

The problem for both sides was the same – resupply. Reinforcements, tanks, ammunition, food, and oil to keep their voracious armies on the move. For the British these came, for the most part, in convoys around the Cape of Good Hope to Alexandria via Suez, a long and hazardous journey. On paper the problem for Rommel seemed simpler – his resupply came from Italy, a much shorter journey; but his convoys were under serious threat of attack, principally from Malta.

The British Army relented its decision to oppose reinforcement of the island and eventually some 30,000 troops were stationed there. For its part the Axis more than once – the Italians in 1940; a proposed German-Italian campaign in 1942 – gave serious considered to an invasion. Perhaps Malta’s diminutive size was its saviour for it never was invaded, Rommel in particular preferring more grandiose headline grabbing operations. This was a substantial error. As is evident from his own writings, Rommel never had enough of anything, troops, tanks, oil – especially oil – and he firmly blamed depredations from Malta for his difficulties. It was, therefore, essential to keep the island as an operational base, the problem in its turn being to keep it supplied. This, inevitably, was not easy, the island being subject to ferocious air attacks by German and Italian forces based in Sicily, and supply convoys having to run the gauntlet of attacks by Axis surface and submarine naval units. The Pedestal convoy of August/September 1942, which included the tanker Ohio, was, after many failed attempts, the last chance to keep Malta from having to surrender.

Mike Pearson.

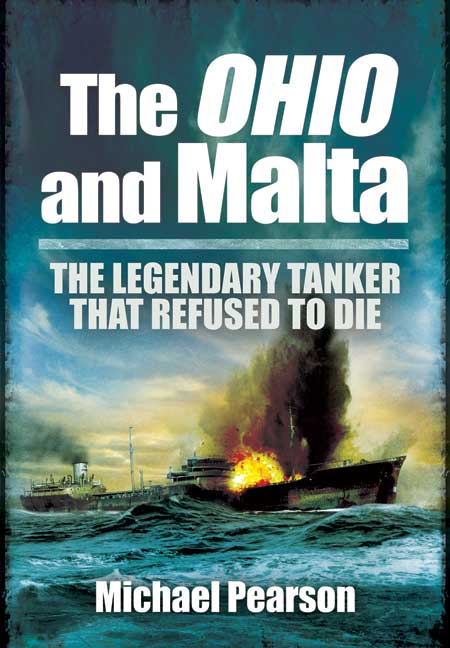

The Ohio and Malta is out now in paperback and eBook editions.