Author Guest Post: Matt Merritt

The Mystery Towers

In 1915, aged 26 and recently married, Joseph Gurney Ripley would set out from his new home in Southwick, West Sussex, with his camera. He was a professional photographer, which was even then a precarious trade. He’d started his career during World War One when the photographic industry was very much in recession. Unable to make a living, many a photographer had given up because there was no call for their services. Determined to carry on, the talented Mr Ripley would spend hours wandering the Sussex Downs, Southwick and Shoreham-by-Sea looking for that saleable picture. Throughout the First World War and afterwards would print up these photographs as cards for sale.

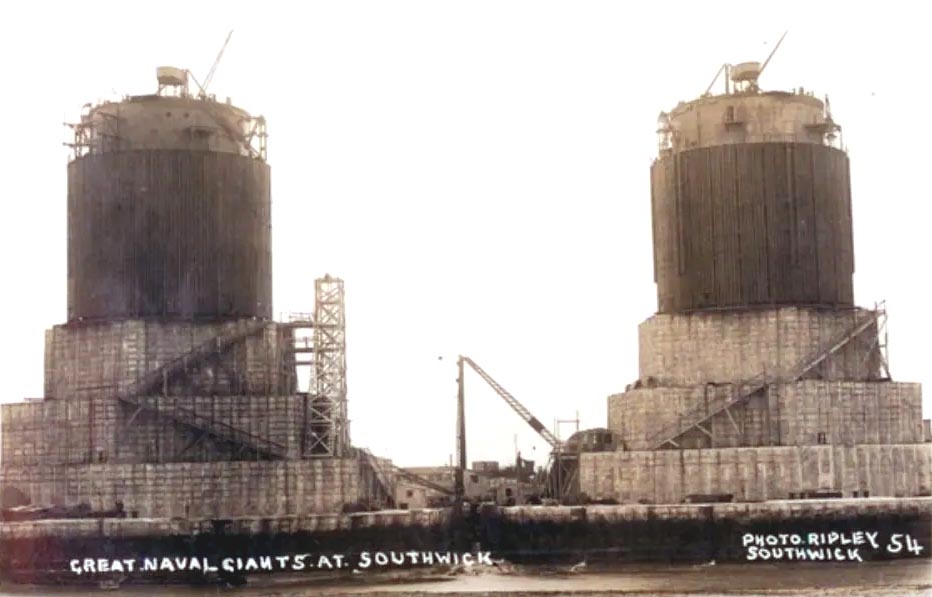

In 1918, Joseph Ripley photographed the army encampment of wooden huts on Southwick Green. These had been built by and were inhabited by Royal Engineers who were working on a secret project at Shoreham Harbour. However the project, was to build the colossal concrete Mystery Towers, and didn’t stay secret for long. Mr Ripley photographed the construction of the towers and printed up an estimated 65 to 75 different postcards of them. He often titled them the ‘Naval Giants’ and sold the cards in great volume to the curious public. Despite their supposed secrecy, he was allowed to take a picture from the top of one these towers, looking east towards Brighton.

Construction of the two huge concrete towers, at Shoreham harbour, had begun in the spring of 1917. The concrete tower bases were built on dry land before being floated into position in the harbour itself. The bases were hexagonal in shape, made up of honeycomb cells. These cells, when empty, allowed the tower to float and be towed by a ship, but when flooded with water they enabled the construction to sink in the sea to a depth where only the actual tower would still be on the surface. Each base had three concrete tiers built on it, diminishing in size as they rose, giving the towers one of their nicknames – the Wedding Cakes.

Each entire construction was 170 feet across at the base and 190 feet tall. The 50-foot high, round turret was made of steel girders clad in timber. A smaller round turret was perched on top of the larger one. Made of steel it was topped by cranes capable of lowering equipment or boats, and the base was designed for an anti-aircraft gun to be mounted on it. Inside there was submarine detecting equipment and each tower was equipped to house ninety men at sea.

The Mystery Towers were designed by G. Menzes and built by the Royal Engineers for the Royal Navy. Shoreham was chosen as the construction site partly because of the amount of shingle available to help make the concrete. Also a dry dock could by constructed at the harbour’s eastern end, conveniently served by a single-track railway to bring in building supplies. The workers were housed in a camp of huts at Southwick Green and at their peak the civilian and military personnel working at the site numbered between 3000 and 5000.

Working both day and night, the men completed two towers, finished the bases for two more and had others under construction, by the end of the war. Costs had rocketed to 2.5 million pounds for the first towers. Now with the end of hostilities, the towers that had been built for a mysterious wartime purpose had no practical use and construction stopped.

Still the authorities did not reveal how the towers would have aided the war effort.

One of the most plausible theories suggests that Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, intended having around fourteen of the towers built and lowered to the seabed across the straits of Dover, a mile or so apart. With only their steel towers above the water, each would have been manned by a gun crew, with anti-submarine nets and mines sunk between them. The purpose would have been to stop German submarines from entering the English Channel.

After the end of the First World War, the two fully constructed towers did cause an obstruction, not to enemy vessels but to ships using Shoreham harbour. For a while they were just left there to rust. Then on the 12th of September 1920, one tower was slowly towed out of the harbour by five tugboats, watched by crowds of curious onlookers. It began a laborious forty-one mile journey to a sandbank beside the Isle of Wight. Named Nab’s Tower, it took the place of the old Nab’s lightship that had previously protected ships from running aground at Nab’s Rock. When the base was filled with water and it was sunk, it started to list and still rests there at an angle to this day. During the Second World War two bofors guns were mounted on the tower, and it finally took a wartime role, shooting down enemy planes.

At first Nab’s Tower was a manned lighthouse with a crew of four, but now unmanned, it is still used as a weather station and lighthouse, with its top now converted to be a helicopter-landing pad. In 1999 the tower was damaged after a ship collided with it but it has subsequently been repaired.

The public were for a time allowed to board the second complete tower in Shoreham Harbour, for a fee that went to the Royal Sussex County Hospital. Too large to pass through the harbour mouth and move on to a new home, this tower was eventually demolished between 1923 and 1924. Debris from the tower was used improve the seawall at the South East of the harbour.

Joseph Ripley died on 26 July 1933 aged 44, but his wife Amy continued running his photographic studio in Southwick, Sussex until the end of that decade.

Matt Merritt

Matt Merritt’s book ‘The Royal Engineers In Korea’ will be published by Pen and Sword in April 2024.