Author Guest Post: Kim Thomas

‘The devil made me do it’: a story of crime and madness in nineteenth-century London

On 29 December, 1888, 35-year old Julia Spickernell, a mother of four, asked her downstairs neighbour, Mary Ann Goldring, to look after her three older children so that she could clean the stairs. While the children were out of the way, she filled a bucket with warm water, picked up her youngest child, nine-month old Mabel, put her in the bucket head first and drowned her.

There was little in Julia’s background to suggest that she was capable of murder. She came from a respectable lower-middle-class family (her father was a policeman), and her husband Frederick worked as a telegraph clerk for the Submarine Telegraph Company. The couple lived at 93, Milton Street, a three-storey house in Stoke Newington, with their children: Emily (8), Frederick (6), Edith (2) and baby Mabel. Julia had given birth six times in eight years: two of the babies had died at only a few months old.

Julia was breastfeeding Mabel, as she had all her children. Signs that something was wrong had begun a few weeks earlier. Julia had started experiencing pains in her head and back, and she was also worried about Mabel, because she had bronchitis. On Christmas Eve she lost her temper with her husband – as she went into the kitchen to wash one of the children’s night-dresses, Frederick told her not to in case she caught a chill. She flew at his throat and said: ‘Oh Fred, I will murder you; I will murder you and then I shall be a murderess.”

After Julia killed Mabel, she made no attempt to hide what she had done. She ran to Mary Ann’s apartment and insisted that Mary Ann and her servant come and see what she had done. Mary Ann fetched another neighbour, Lucy Cavalier, who sent for a doctor. Julia told Lucy: “I have done it! The devil made me do it; he has been following me about up and down stairs the last five weeks.”

At the initial police court hearing (equivalent to a magistrates’ hearing), the police surgeon, Dr Jackman, confidently asserted that Julia had been suffering from “homicidal mania, consequent on the over-secretion of milk”. Julia herself was described as “downcast” at the hearing and, asked if she wanted to say anything, replied, in a low voice: “No, sir.” When she was tried a few weeks later at the Old Bailey, Julia’s family doctor, Dr Spencer, the Holloway prison doctor, Dr Gilbert, and Dr Jackman all gave similar evidence. They testified that they thought Julia had killed Mabel in a bout of insanity caused by excessive lactation – a common nineteenth century diagnosis based on the belief that some women could be driven mad, after birth, by producing too much breastmilk. Dr Spencer further said that he had known the family for some years, having attended Julia at the births of her children, and that Julia had been a good, kind mother.

To reach a verdict of insanity, the jury had to be convinced that the case met the requirements of the McNaghten rule, which stated that the defendant was so insane they were unable to understand that what they were doing was wrong. The rule arose from an 1843 case, in which a man called Daniel McNaghten had assassinated the Prime Minister’s secretary, Edward Drummond, mistaking him for the Prime Minister himself.

Looking at the evidence with a sceptical eye, we can see that Julia’s case did not meet the McNaghten test: Julia did know what she was doing in drowning her baby and also knew that it was wrong. Yet as her comment about the devil suggests, she felt unable to stop herself.

Luckily for Julia, the doctors were on her side, helpfully guiding the jury to an insanity verdict. In the words of the legal expert Nicola Lacey, they “tailored their evidence carefully to the doctrinal requirements of the McNaghten Rules.”

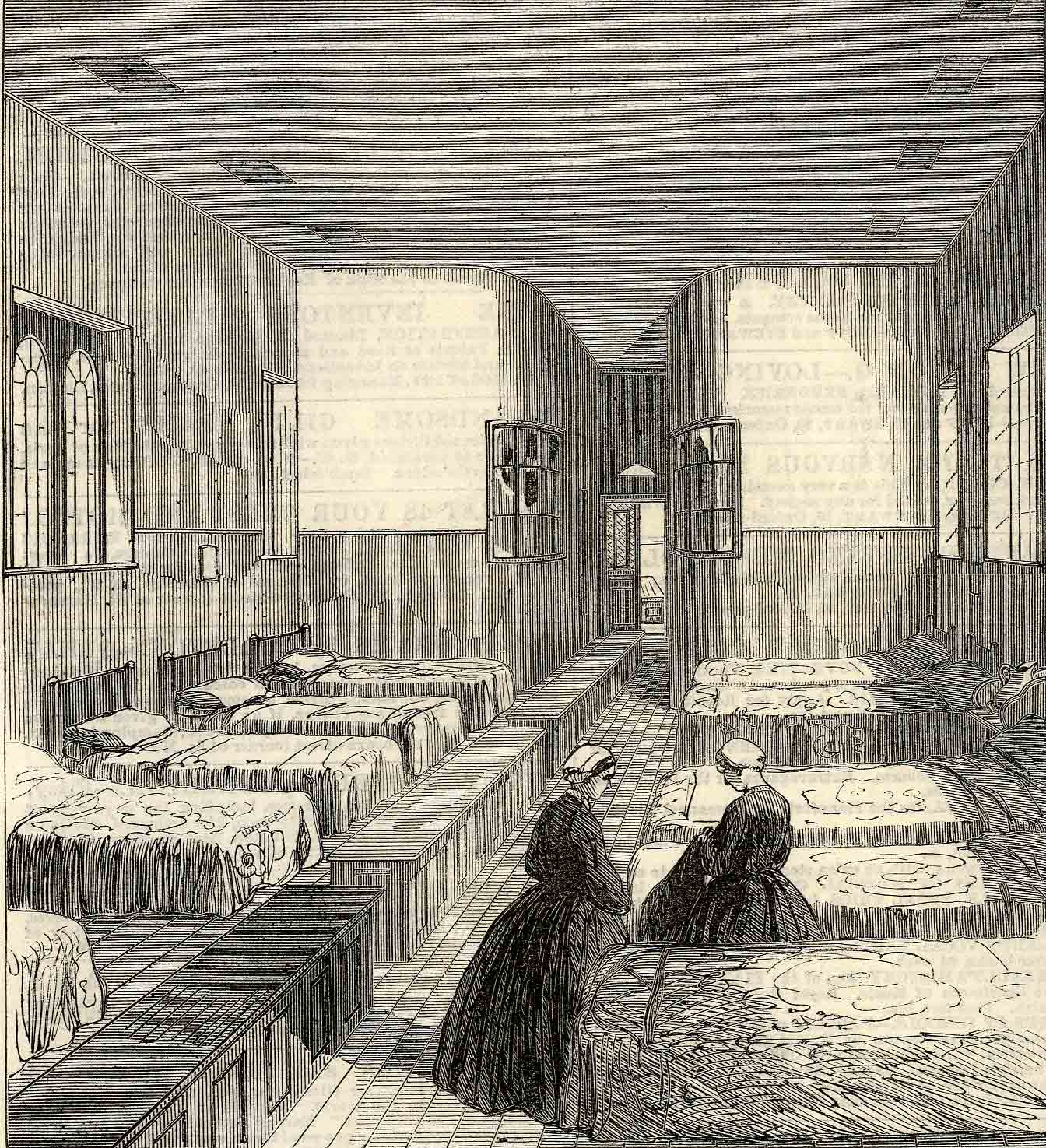

If Julia had been found guilty of murder, she could have expected to spend the rest of her life in prison. (No one had been sentenced to death for killing a baby under one since 1849.) Instead, she was sent to Broadmoor, the asylum for criminal lunatics, where she made a good impression: the medical superintendent, David Nicolson, described her as a “respectable looking woman with a pleasing address and manner.” The regime at Broadmoor was a benign one – although patients were expected to work, they were also able to take walks in the pleasant tree-lined grounds, play backgammon and read magazines in the games room.

Nonetheless, it was hard for Julia to be separated from her family. She and Fred had an affectionate marriage, and he visited her frequently. She was desperate to return home, and Fred wrote to the Home Secretary several times asking for her release, but she was deemed too ill to be let out. After seven long years in Broadmoor, however, the medical superintendent decided she was well enough to leave, and she returned to Fred and the children, now living in Forest Gate, in East London.

We can’t know whether Julia ever recovered from the trauma of having killed her daughter, or the grief of having missed seven years of her children’s lives. But we do know that she and Fred stayed together, and that Julia outlived him. In her final years, she was looked after by her adult children before dying, at the ripe old age of 91, in 1944. We have come to think of the Victorian judicial system as harsh and punitive. In Julia’s case, however, it showed another side: one that was willing to bend the rules in the service of a compassionate outcome.

Broadmoor Women is available to order here.