Author Guest Post: Julie Cook

We have a guest post from author and journalist Julie Cook. Here Julie explains her family connection to the Titanic, and the research that went into writing The Titanic and the City of Widows it left Behind.

You can preorder a copy here.

Why Titanic is not just a rich person’s tragedy

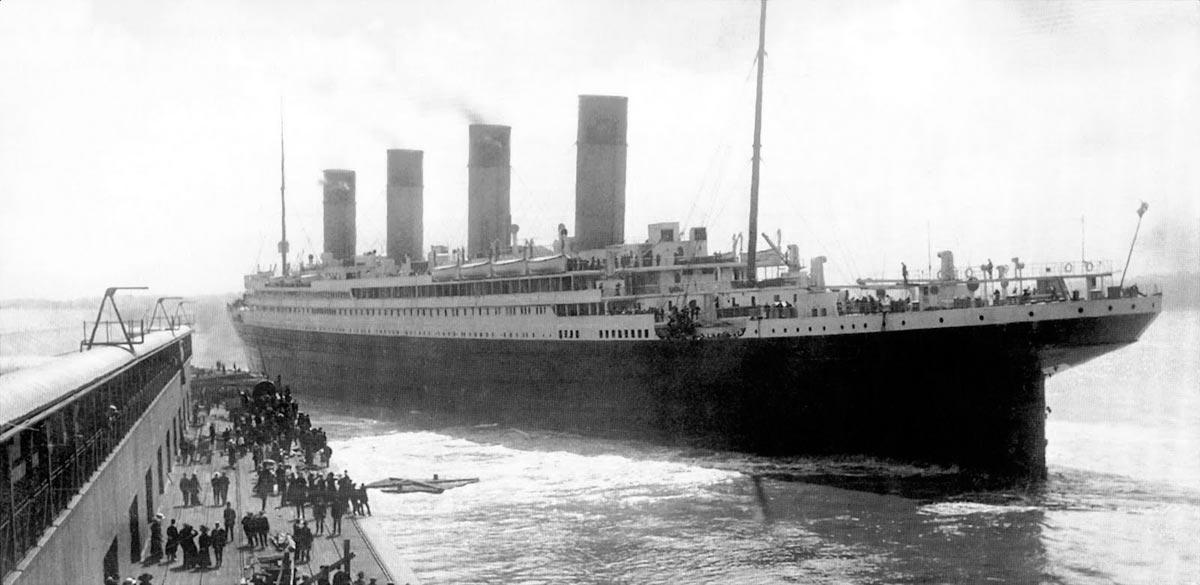

You see it in virtually every adaptation, documentary or film – the elaborate staircase, the luxurious suites, the lavishly decorated restaurants.

Titanic may be at the bottom of the Atlantic ocean but she is very much here in our collective thoughts and imaginations as a rich person’s playground of floating luxury.

I always saw it this way too.

Until my father explained to me that we had an ancestor who died on board. He was my dad’s grandfather, and my great-grandfather William Bessant.

William had worked as a fireman on the ship. Unlike the well-known images of first class passengers, of the famous names and the lavish interiors, the men working as firemen in the ships’ boilers are not well-known. Invisible, perhaps.

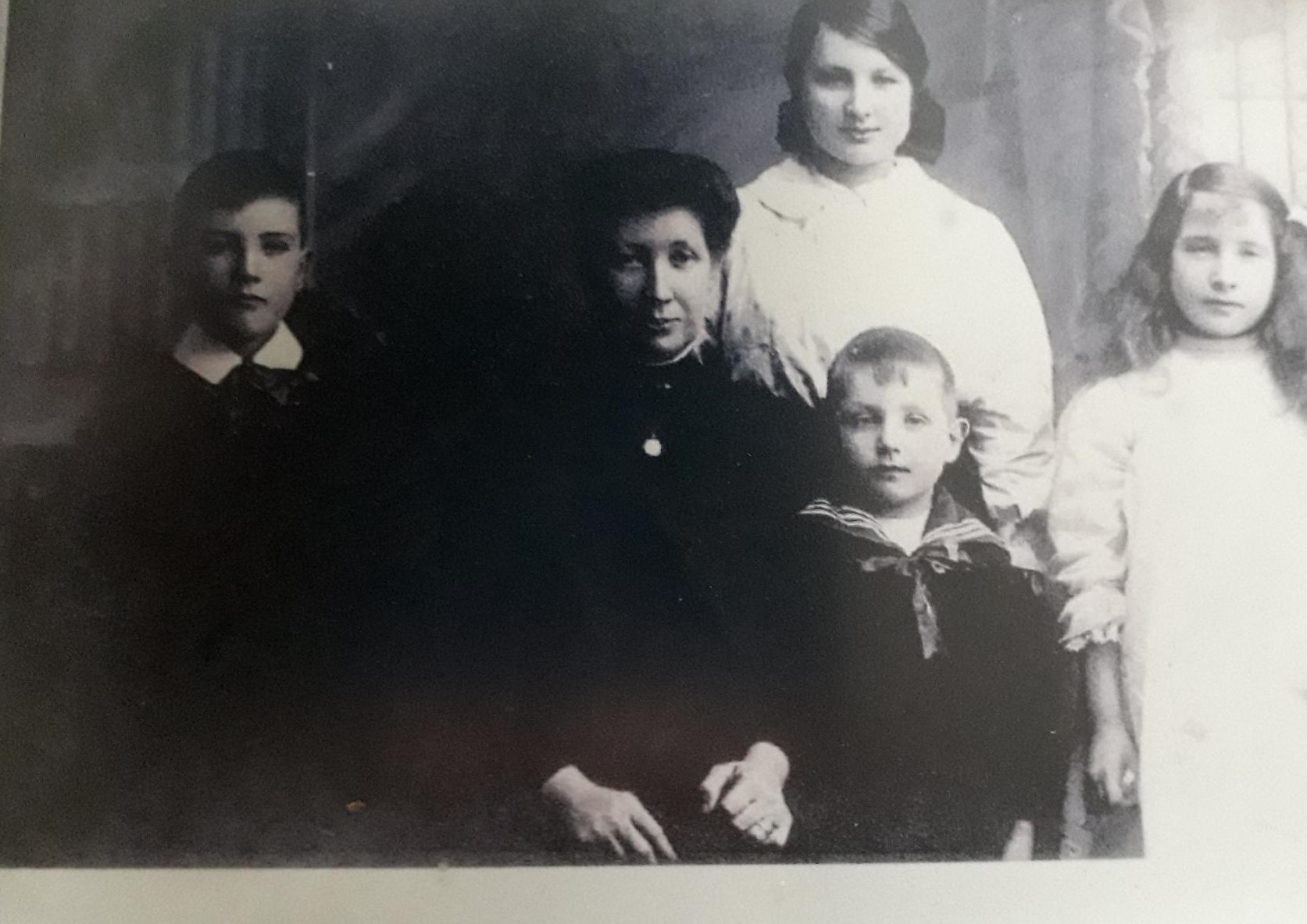

William had taken his job on Titanic to feed his wife, my great-grandmother, and her five children. They were poor – as were the families of the many other firemen, stewards, cooks, victualling workers and bellboys who worked on Titanic.

When we watch the glamorous adaptations and films of the first class passengers walking, heads held high, into first class, what we don’t see are the stokers hunched under their kit bags trudging on below decks.

Just as society was very much laid out in strata, so were the decks of Titanic. While the rich in first glass sipped tea out of fine bone china teacups, my great-grandfather was hard at work in the boiler room, shovelling coal into the furnaces by hand to keep the ship sailing.

My father would often angrily explain that Titanic was always portrayed as a rich person’s tragedy, while the poor who perished were so often ignored.

As I grew up, I saw how true that was.

I never saw anything about the firemen who died, or the stewards, or the other workers who lost their lives. Yet I saw the same big names pop up again and again and again.

And so I began to plan a book. I wanted to write about Titanic from a personal perspective, of losing an ancestor and the knock-on effect that permeated down the years. But I also felt other voices were not being heard – the voices of the wives and children who had to carry on when their breadwinners died.

My father told me that Emily, my great-grandmother, had to take in laundry to feed her children when William died. When I became a mother myself, that made me feel both pity and anger.

Where were these women’s stories? How did they manage when their husbands or sons vanished beneath the waves?

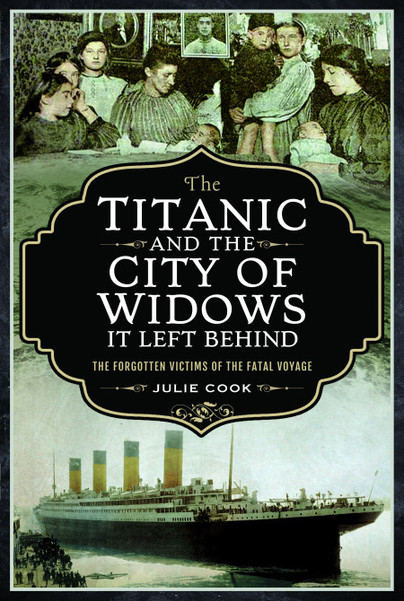

And so the idea for my book took shape. It would not be about the ornate interiors, or the succulent dishes served on board. It would not be about the multi-millionaires of the day who sailed on that fateful ship, or the high society in first class.

It would be about men like my great-grandfather and about women like my great-grandmother. The aim was to give the workers and their families a voice after 100 years of silence.

I trawled social media and found descendants of crew who had died or survived. I met with them and heard their stories, viewed their photos and documents. Some of them had ancestors who had been firemen on the same shift as my own great-grandfather. It was eerie – and yet wonderful – to finally find people who understood the other side of the Titanic story: the poorer, darker side.

I then trawled through the local archives in Southampton. I read through the Titanic Relief Fund minute books – the documents detailing the huge amounts of money raised for these families and how the money was doled out.

There were fascinating entries – from women receiving new pairs of false teeth, to women receiving emergency bags of groceries to survive another week. But these women – although supported hugely by the charity money – still lived their hard lives. It was still a struggle for many.

I re-watched many of my old Titanic favourites – A Night to Remember, Titanic, and sat through many documentaries ranging from conspiracy theories to the foods that were served on board.

But still, the workers were no more than ghostly figures. Their stories were mentioned but never told in full. Titanic, it seemed, was destined to always be portrayed as a rich person’s tragedy – despite just under 700 crewmembers dying on board.

My book The Titanic and the City of Widows it Left Behind will be published this March 30th . Inside it lie the stories of women who lost their homes when their men died on Titanic, women who were so malnourished they needed hand-outs of food, women whose children had to be taken away and children who, despite it all, managed to succeed in apprenticeships or even followed their fathers’ footsteps and went back to work at sea.

Like any author, I am excited that my book will be published this year. But I am genuinely also excited that at long last Titanic will be seen from the other side; its darker, poorer side. My father often told me that Emily, my great-grandmother, never talked about her loss after William died.

‘People like that didn’t talk about it, they carried on,’ he said.

Unlike the rich who, if they perished were lauded as heroes and if they survived were eloquent enough to put their survival stories into words, the poor could not do this. They – by very nature – had to put their heads down and carry on. Hence, their stories are not known.

It’s my hope that my book will bring these working class stories to the forefront, to show that Titanic was not just a rich person’s tragedy. It is my hope that the nameless, faceless crew who perished and their poor families might become known at last.

The Titanic and the City of Widows if left Behind is available to preorder now from Pen and Sword Books.