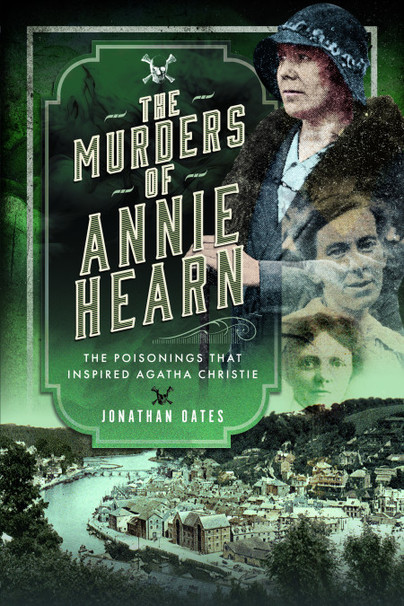

Author Guest Post: Jonathan Oates

Women only make up a small minority of murderers, but when only poisoners are taken into account they make up a larger percentage. Mary Ann Cotton and Florence Maybrick may well come to mind here. In the early twentieth century there was the case of the woman known as Mrs Annie Hearn.

Was she a kind hearted neighbour who nursed friends and family, a church going widow whose late husband was an army doctor and who bought Christian tracts? Or was she a cold hearted poisoner of several family members and friends?

Annie Hearn was born Sarah Anne Everard in Lincolnshire in 1885 of a respectable family. Her aunt, Mary Ann Everard, trained her as a cookery teacher in the early twentieth century. However, she was recalled to Derbyshire, where some of her family had moved to, for some were very ill. Annie nursed her mother until she died in 1915 and then one of her sisters, who died in 1917.

Annie then looked after her older sister, Lydia, who was also unwell. The two were living in Cornwall by 1922 when they began to care for an elderly widow, Miss Aunger. The three were living in the little Cornish village of Lewannick. Mrs Aunger died and in 1926 the sisters’ aunt came to stay. She was aged, too, and so when she died later that year, it was no surprise.

The sisters also became friends with Mr and Mrs Thomas, who were small farmers and their nearest neighbours. In 1930 Lydia became increasingly unwell and sickly. She had never been strong and was nursed by Annie, as well as being visited by two local doctors. In July that year she died and was buried alongside her aunt in the churchyard.

Doubtless feeling sorry for their once again bereaved neighbour, on 18 October 1930, the Thomases took her out to the coastal town of Bude for afternoon tea. Annie brought salmon sandwiches along for then to eat in the café (as well as Thomas ordering tea and cake). It all seemed to be going well, but on their drive home, Mrs Thomas was sick.

A doctor was called and the farmer’s wife seemed to be suffering from food poisoning. The kindly Annie offered to stay at the farm to help with cooking and nursing whilst Thomas ran the farm. He was happy to accept, but despite further visits by the doctor, his wife did not return to good health. Indeed, her condition worsened and despite being sent to Plymouth Hospital, she died on 4 November, aged only 43.

It was at the funeral that her brother, Percy, voiced his suspicions to Annie, having found that his sister became ill after eating the sandwiches prepared by her. Meanwhile, there had been a post mortem and quantities of arsenic had been found in the body. An inquest was announced, but the key witness, Annie, disappeared, after leaving a note which might suggest suicide but also that she was innocent.

Suspicions grew and the bodies of Lydia and Mary were disinterred, and were found to have arsenic in them, too, more than would normally be expected. There was a search for Annie and a reward was offered for her discovery, assuming she was still alive. It was also found that she had only pretended to be a widow of an army doctor by the surname of Hearn and that she had never been married. Eventually she was located, working as a housekeeper for an architect in Torquay.

Annie was charged with the murder of Mrs Thomas and her sister. Experts such as pathologist Dr Sydney Smith thought she was innocent, and he assisted Norman Birkett, a noted barrister, in her defence at the Assizes. They argued that there was no real proof of murder and no clear motive, whereas the prosecution suggested she might have wished to marry Thomas and could have inserted arsenic into the salmon sandwiches.

Annie was found to be not guilty. This led some to assume that the killer must be Thomas, motivated by a wish to marry another woman. Annie herself never gave an answer as to how her sister and her friend met untimely ends, except that she was wholly innocent of such and to suggest otherwise was outrageous. She died in Shrewsbury in 1948; Thomas in 1949.

The question is which of them, if either, was a killer. Those writing about the case in the last century have come up with three different solutions. The first is that it is an insolvable mystery. The second is that Annie was innocent and that Thomas was guilty. More recently, a new consensus has emerged and it will be interesting to see how long lasting this is. Possibly access to the Cornish police file on the case, which will be available in 2030, will shed fresh light onto the case (the Assize files, including the diary of Lydia for her final months are open to researchers at the National Archives).

The probability is that for all her apparent kind heartedness, churchgoing and charity, Annie was a deeply psychologically disturbed woman. She seems to have been a fantasist who could not distinguish the boundaries between daydreaming and reality. She wanted to be married, so conjured up a fictional husband who she talked about as if he was real. Thomas had lent her £38 and often visited the sisters’ house with little gifts and provided company for them. He preferred Annie to her invalid sister, but she could not bear to share him with her – or with his wife.

Annie had bought weedkiller, which contained arsenic, just prior to her aunt’s death which may well have been no coincidence, and Annie was the sole beneficiary of her will. Her sister and her friend had all the symptoms of arsenic poisoning such as numbness in the limbs, a dry throat, difficulty in digestion and sickness. There can be no doubt that both had been poisoned and little as to who the culprit was. Alas, she had got away with murder.

Order your copy here.