Author Guest Post: Jan Gore

The V1 flying bomb campaign: the Christmas Eve Blitz, 1944

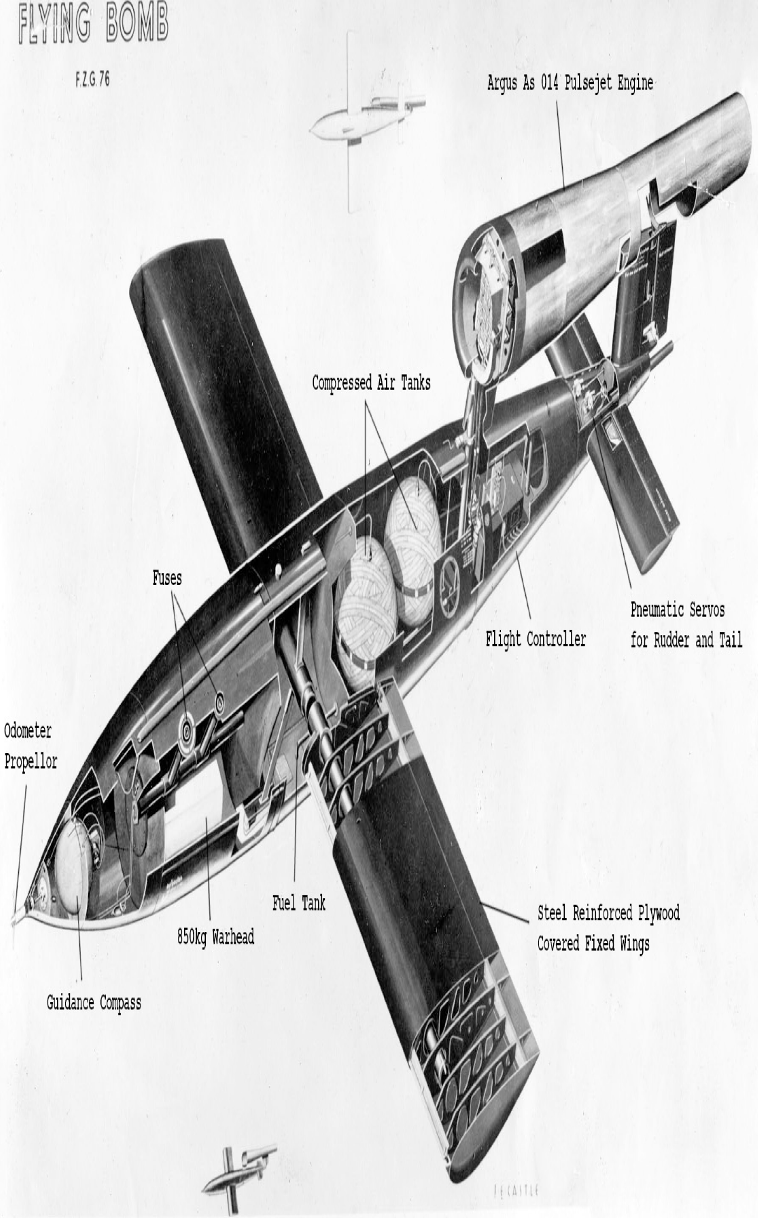

Many people will already know about of the V1 flying bomb, otherwise known as the doodlebug; it was a pilotless plane, originally launched from ramps in France. It was designed to cause maximum damage to people and property both cheaply and effectively by flying along a preset course until it crashed and exploded.

The V1 flying bomb campaign began in June 1944. The first ten weeks were the most dramatic, with attacks by day and night. However, once the Germans were driven out of France and the launch sites could no longer be used, it was imagined that V1s could no longer be sent off from along the Channel coast. In early September Duncan Sandys announced: “We have beaten Hitler’s secret weapon, the V1”. However, the V1 would continue to be part of the war until the following March.

In the early hours of 24 December, the Christmas Eve raid began, using air launched V1s. Almost all of Kampfgruppe 53 took off, up to 45 Heinkels, each carrying a V1 under its starboard wing. These flying bombs were then launched over water and sent on their preset course, with the Heinkels travelling almost due North to carry out their launches; these took place over a period of about an hour, between 05.00 and 06.00 and each missile took about 30 minutes to complete its flight after the air launch had taken place. (The Germans had calculated that vigilance would be at its lowest in the early hours of the morning, and they were correct.)

The air launch procedure was very dangerous for the pilot of the Heinkel and its crew. In essence the aircraft itself became a flying bomb. The additional weight made it harder for the Heinkel to gain height; once it was over the sea it had to fly almost at wave height to try to evade British radar. It then had to climb to establish launch height, and the pilot had to fly fully illuminated for the two minutes of the launch. After that he could head for home.

In all 31 V1s made landfall and reached the target area that morning, between 05.28 and 06.25. One V1 crashed into the mud of Humber, engine still running. The area extended between Spennymoor to the north and Woodford to the south; its intended target was central Manchester. In this endeavour, it failed, but 15 V1s fell within the Manchester area. Many of the remaining doodlebugs fell in rural areas or over fields. However, the total death toll came to about 50 people, while over 100 were seriously injured. Some remained in hospital until well into the New Year.

One V1 flew over Manchester, east to west, before coming down three miles west of the city. It flew over Booth Hall Children’s Hospital at about 05.30. The London evacuee children there were woken by the noise; they immediately recognised it as a doodlebug, based on their prior experience at home and cried out to those in the ward to take cover.

By far the largest incident was at Oldham, where the siren sounded at 05.30. Twenty minutes later, a V1 made a direct hit on number 145 Abbey Hills Road. There were at least 32 named victims, with a further 7 or more initially unidentified. (A number of people had travelled to relatives at that time so were not listed as part of the area’s population.) 67 people were seriously injured, with 38 victims treated at Oldham Royal Infirmary, and hundreds of homes were damaged, maybe as many as 1000. This was a densely populated area with many closeknit families living along Abbey Hills Road.

Everyone was preparing for Christmas. Families were coming together to celebrate. Aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews were meeting at the family home to ensure they could spend the day together. Sons and daughters in the services who had been granted Christmas leave had already made their way back to their parents. In many cases the tables were already being set, ready for the festive meal. The main dish might be only “murkey” (mock turkey, “without a feather in sight”): a mixture of sausage meat, breadcrumbs, onions, apples and parsnips, but it would still be very welcome. People were looking forward to their first chance in months to spend time together.

Some households had an extra reason for celebration. A family wedding party had been held at 151 Abbey Hills Road. The house was full of visiting family, sleeping several to a bed, with at least twelve staying overnight; a number of cousins had come from Chesterfield to visit the family and were planning to stay until Christmas. Four of them died during the incident and one died later; several others suffered life-changing injuries. Fortunately, the bride and groom had gone to stay a short distance away.

Further along the road, two young sons died at home; one was on Christmas leave from the Navy, while his brother was a sea cadet. An air raid warden saw his house being bombed and ran to the rescue; his young wife survived but his two small children were killed. They were buried in the same coffin. He had to break the news to his sister on Christmas morning and for many years the family felt unable to celebrate Christmas. Other victims died as much as a month later.

The V1 left presents and Christmas trees scattered in the rubble. Walls collapsed and there was glass everywhere. Any food already laid out was covered with plaster, while bedding was left festooned on the branches of trees like some strange decorations. Dust made it hard to breathe and there was a smell of gas. An incident inquiry point set up shortly after 06.00 handled 450 inquiries in the first two days alone, as local residents tried to locate friends and relatives.

In Tottington, near Bury, at 05.50, another V1 killed six people and injured 14 when it destroyed a row of terraced houses near the church. It took ten hours to remove the casualties. 53 people were made homeless.

Just after 06.00 on a bitterly cold morning, the air raid warning sounded near Hythe, 20 miles east of Manchester. A mother and daughter were about to take shelter. They could hear the engine and assumed the noise was a plane. Then they heard the engine stop. There was a loud explosion. The house shook, the roof rose and then fell, and the daughter was thrown out of bed. She was rescued shaken but unharmed.

A nearby dairy farm was less lucky. The farmer was already up and about to start the milking. His mother-in-law had come to stay for Christmas. The farmer’s daughter was sharing a bed with her grandmother, which may have shielded her from some of the blast. Both the farmer’s mother-in-law and his son were killed by the V1. The farmer’s wife was left with permanent eye damage, and the farmer was badly scarred. They and their daughter were taken to hospital and remained there till after New Year. Six cattle were killed or fatally injured and the pony that did the milk round had to be destroyed. The farmhouse was completely destroyed and when the farmer returned home, he discovered that his house had been looted. He lost the desire to farm and built a new house.

These are just some of the incidents from the Christmas Eve Blitz. To learn more about the campaign, see my book: