Author Guest Post: James Goulty

Eyewitness Korea: The Experience of British & American Soldiers in the Korean War 1950-1953

Today Korea is often dubbed the ‘Forgotten War,’ and certainly there’s a feeling among Korean War veterans that it has been overshadowed in the popular consciousness by later conflicts such as Vietnam, the Falklands, and the lengthy engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan. A former American soldier who’d served with 1st Cavalry Division in Korea during 1950-1951, commented: ‘I gotta bad attitude about it and I hate to say it but I do. Anything you hear today is Vietnam, Vietnam, or Afghanistan but you don’t hear a damn word about the Korean vets.’

Yet, set against a backdrop of global confrontation between Communism and Capitalism, and with the threat the situation would escalate, the Korean War was a significant event of the Cold War, the ramifications of which are still being felt today. At present (November 2022) tensions on the Korean peninsula remain high. The North Koreans have been conducting numerous missile tests, and placed artillery barrages close to South Korea, allegedly in response to ‘Vigilant Storm,’ a large-scale joint military exercise held by the Americans and South Koreans.

Initially, Western powers under the auspices of the United Nations, proved ill-equipped to oppose the North Korean invasion of her southern neighbour in June 1950. American units rushed from occupation duty in Japan, were typically under-prepared and under-equipped. One veteran NCO recounted how the men in his platoon weren’t well-trained infantrymen, but ‘cooks, medics, jeep and truck drivers, and clerks and they had no battle experience.’ Over the next few months defeat at the hands of the communists appeared possible.

Then in September, ground forces of the American led United Nations Command (UNC) broke out of the Pusan Perimeter, in conjunction with an audacious amphibious landing at Inchon, 150 miles to the north and within striking distance of Seoul. This changed the course of the war. Troops in the Pusan Perimeter advanced north and on 26 September linked-up with those who’d landed at Inchon, simultaneously Seoul was liberated.

By late November, UN troops were virtually on the Yalu River, the Korean-Chinese border. This prompted China to enter the war, and thousands of her troops hurled the UN forces back, aided by the terrain which had separated the Eighth Army advance in the west from that of X Corps in the east. By the end of 1950, the Eighth Army had been forced back to the line of the 38th Parallel, the political border between the two Koreas, and survivors of X Corps evacuated.

Spurred on by these events, the UNC gave up the notion of uniting the whole of Korea, and was prepared to seek a negotiated settlement. However, first a renewed offensive by the communists had to be confronted during early January 1951. UN forces then launched a series of limited counter-offensives during late January-March, re-taking Seoul, and leading to the frontline stabilising around the 38th Parallel. The fighting then ebbed and flowed in this area for the remainder of the war. Armistice negotiations commenced at Panmunjom on 12 November 1951, and continued on and off for nearly a year, while troops on the ground endured static warfare, increasingly reminiscent of the First World War.

On assuming the presidency in early 1953, Eisenhower was determined to end the war, and peace talks resumed, leading to the ceasefire agreement of 27 July. UN casualties were approximately 118,000 killed, including around 1000 British. Over 264,000 UN personnel were wounded, and around 93,000 captured. Casualties for the communists are harder to quantify, but must have been in the millions.

Using a wide variety of sources, ‘Eyewitness Korea’ discusses the war based around the first-hand experiences of American and British soldiers. As part of the UNC, these personnel belonged to a coalition that included forces from South Korea, plus ground units from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Philippines, Turkey, Thailand, France, Greece, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Colombia and Ethiopia.

Crucially, the ground war wasn’t fought in isolation. From an early stage the UNC established naval and air superiority, enabling fighting to be contained to the Korean peninsula. Consequently, troops were provided with comparatively high levels of close air support, unhindered by the presence of any credible enemy air threat over the battlefront. Although some new technologies were deployed, predominantly weapons, equipment and tactical doctrine of Second World War vintage were relied on.

Chapter one provides historical background on Korea and the war, plus highlights the physical environment that impacted upon military operations. An underdeveloped road and rail net-work, rugged mountains, and water logged rice paddies were a challenge for highly mechanised Western armies. Winters were awful, something few American and British veterans ever forgot. Contrastingly, the spring and autumn could be pleasant, one senior commander remarked, that the green of the rice paddies, was ‘so rich… it can take your breath away.’

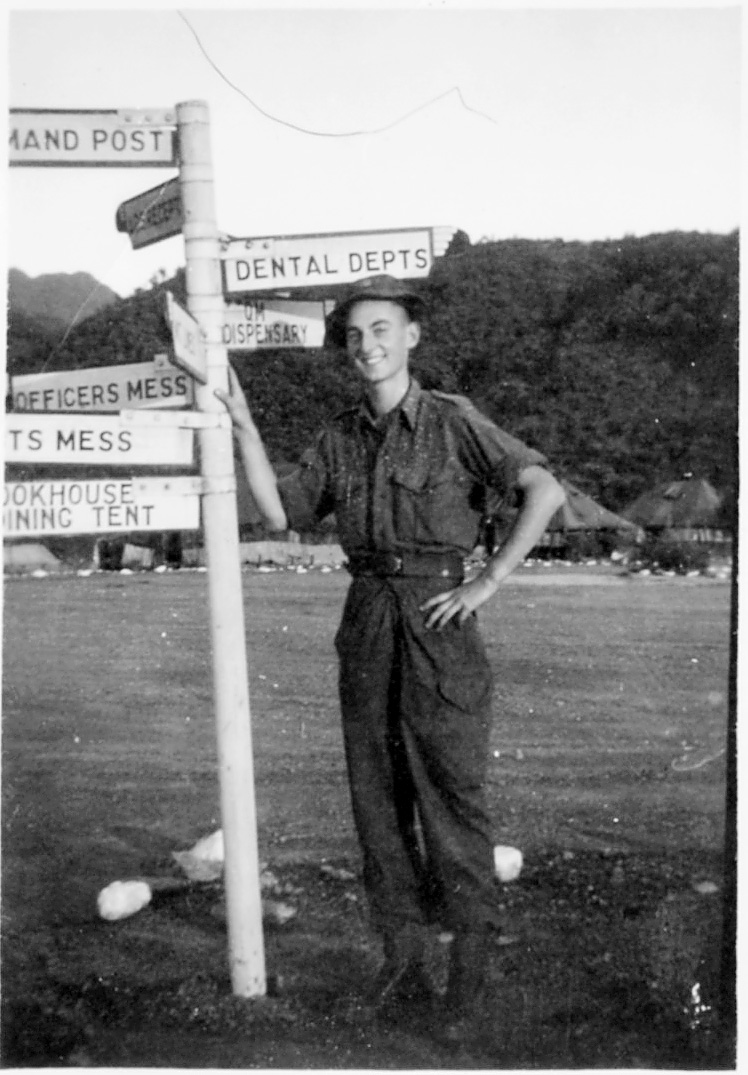

Mobilisation and training comprises chapter two. Alongside regular personnel both America and Britain were initially highly dependent on reservists. These had plenty of experience, but as they’d hastily been pulled away from civilian occupations and families, this made leadership at platoon, company and battalion level infinitely more difficult. As the war progressed, increasing reliance was placed on conscripts (Draftees in America and National Servicemen in Britain), whose inexperience emphasised the requirement for effective training. This had to impart basic military skills, generate a sense of professional pride, and crucially prepare troops to cope with the demands of active service in an awkward theatre like Korea.

Having been mobilised, troops had to be transported to Korea, and this experience features in chapter three. Although some flew there, most were ferried to Korea via troopships, often under unpleasant conditions. Recalling the seasickness he suffered from, one veteran commented, ‘you were being sick until you had nothing left to vomit up.’ Likewise, the comfortable conditions usually enjoyed by officers, contrasted sharply with those experienced by other ranks. Once in Korea, most soldiers rapidly realised they were in an alien, barren land, where the war torn population suffered unimaginable levels of poverty.

Chapter four covers ground warfare c. June-December 1950, and aims to explain what the fighting was like for ordinary troops. As one British officer discovered, the North Korean People’s Army operated similarly to the Japanese he’d encountered during the Second World War, and could ‘fight very bravely indeed.’ Another British soldier, noted how there appeared ‘no such thing as flat countryside… just hilly county,’ and this was extremely physically demanding. Moreover, when UN troops started to encounter the Chinese, their mass assault tactics were a shock. An American infantryman reckoned, ‘… they had no feeling of life… They were just a mass of soldiers. One out of three did not have a weapon.’

Chapter five incorporates discussion on the legendary Chosin Reservoir campaign mounted by X Corps in north-eastern Korea; the impact of General Ridgway in reviving the fighting spirit of Eighth Army, and personal experiences of the limit counter-offensives mounted during January-March 1951. Finally, and importantly from a British perspective, it considers experiences of troops during the Battles of the Imjin and Kap’yong.

Contrastingly, chapter six covers the final two years of the war, when UN troops were tasked with fighting a limit war. As a senior commander stated, if there was to be no military outcome, ‘the next best thing was to make the stalemate more expensive for the communists than for us …to convince them by force that the price-tag on an armistice was going up, not down.’ Accordingly, the chapter deals with the soldiers’ experience of static warfare during late 1951-July 1953, with an emphasis on the nerve-wracking patrolling and raiding that occurred.

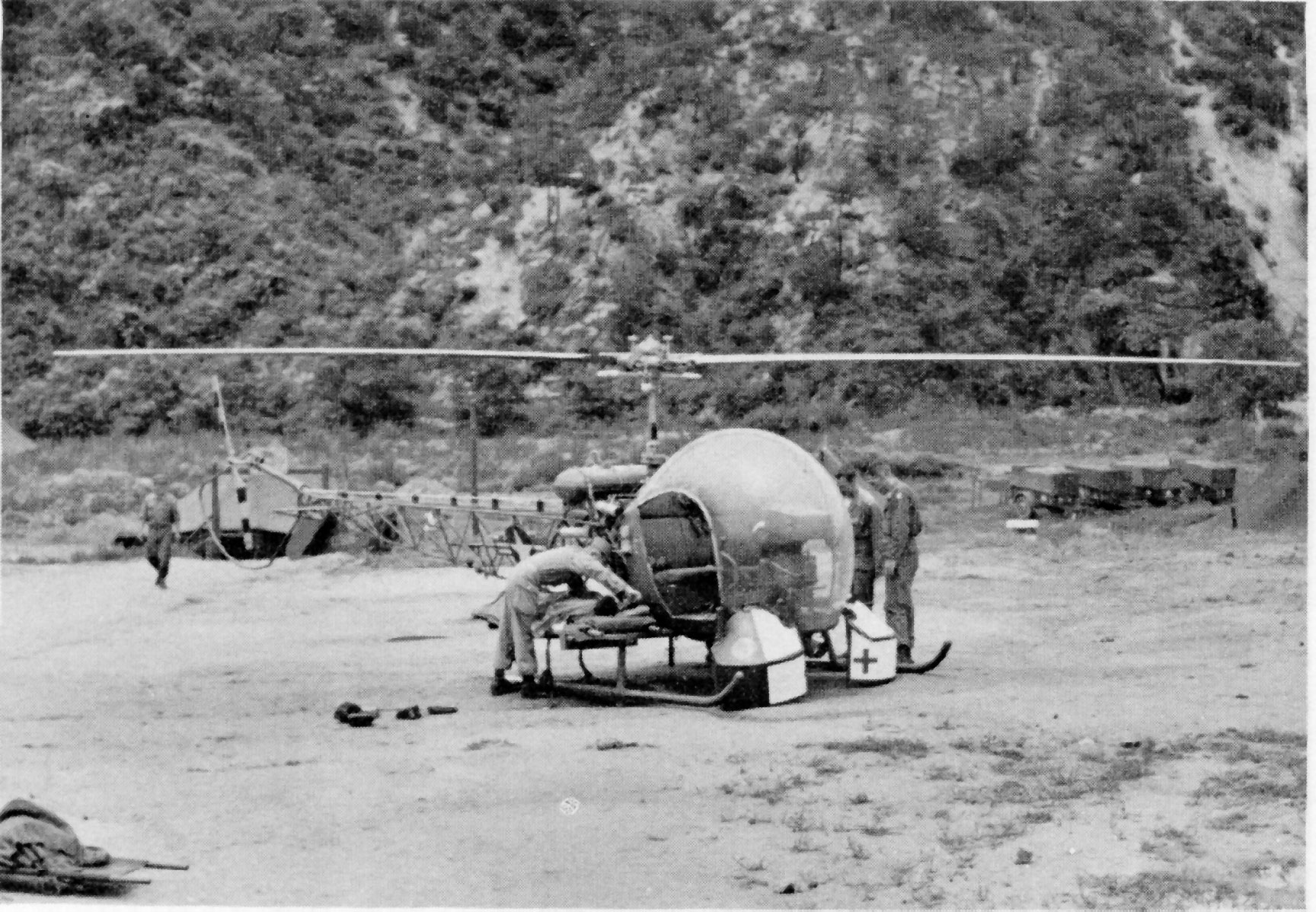

Morale and welfare are covered in chapter seven. Factors that enabled troops to endure the harsh conditions, included food/rations, mail, religion, leave arrangements and access to alcohol and sex. The provision of medical care was important, including the pioneering deployment of helicopters in the casualty evacuation role. Discussion also covers self-inflicted wounds (SIW), frequently deemed an indicator of poor morale.

The experiences of POWs form chapter eight. These men endured many hardships, especially determined efforts at indoctrination by the communists. Many POWs died from starvation, neglect, or were tortured and executed. Those fortunate enough to survive often carried psychological and other medical problems into old age attributed to the conditions of their captivity.

Finally, chapter nine outlines the experiences of troops on completing their Korean tours, plus the implementation of the July 1953 ceasefire. Veteran’s attitudes towards the Korean War and their participation in it are covered. For some the war appeared worthwhile, whereas, others remained less certain given that there was no clear victory.

Hopefully, this book provides an informative, interesting read and a respectful tribute to those British and American soldiers who served in Korea, especially those who never made it back home.

James Goulty

Eyewitness Korea is out now.