Author guest post: James Goulty

Naval Eyewitnesses: The Experience of War 1939-1945

The book draws upon the personal testimony of wartime sailors and merchant seamen, notably from the oral history collections of the Imperial War Museum and Second World War Experience Centre. During the war the Royal Navy was compelled to absorb large numbers of reservists and ‘Hostilities Only’ (HO personnel). These individuals went on to serve on a bewildering variety of warships and smaller craft or even work in hazardous areas such as mine and bomb disposal. According to the distinguished naval historian, Eric J. Grove, total strength was over 863,000 by mid-1944, including 72,000 members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, better known as the Wrens. Although they didn’t go to sea, Wrens similarly performed a wide variety of tasks.

Many of the men and women quoted in the book developed a deep attachment to the Senior Service, and even enjoyed aspects of their service, despite the privations of wartime. However, the war at sea, was equally as brutal and stressful for those participating in it as the war on land or in the air. British naval casualties for the entire war were 1,525 ships of all types lost, equating to over two million tons of shipping, and over 50,000 personnel killed, many from the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR).

A further 28,000 seafarers aboard British merchant ships were killed, and thousands more died from wounds suffered during their war service or in accidents. Equally as significant was the loss of 4,800 merchant ships, equating to 21.2 million tons. Had the supply of food, raw materials, and armaments from overseas been severed, then it is unlikely that Britain would have been able to continue the war. Merchantmen were also important during the various amphibious operations embarked upon by the Allies, as the war gradually shifted towards the offensive. During Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, for example, around half a million tons of shipping was assembled, including fourteen British hospital ships.

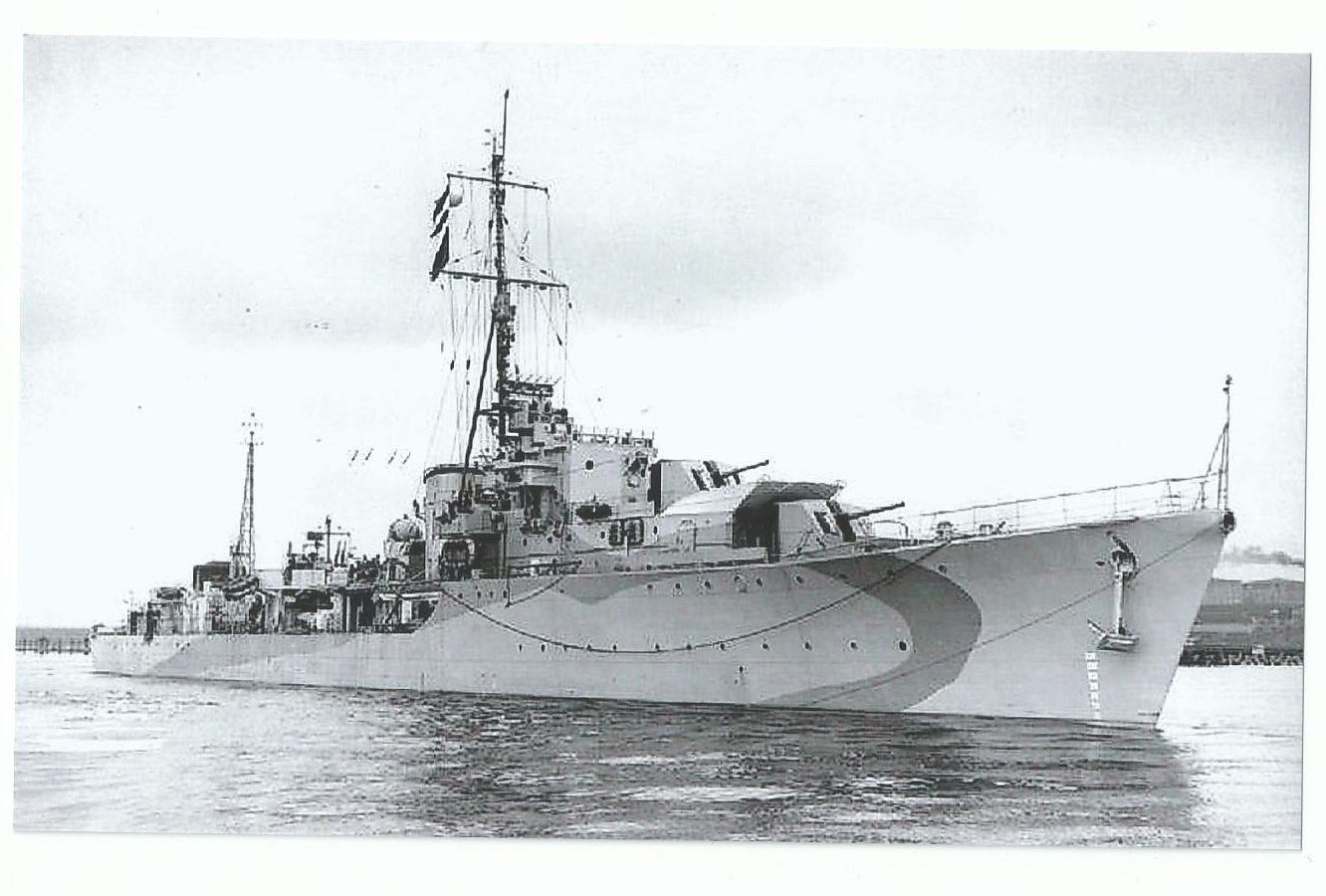

The book is arranged into thematically based chapters. Chapter one deals with life aboard capital ships, such as battleships, and contrasts this with the conditions experienced by sailors aboard smaller vessels, including destroyers, mine sweepers and motor torpedo boats.

Naval aviation and aircraft carriers are covered in the second chapter. The Fleet Air Arm had its own strong identity, but it was deeply unfortunate that tension between the RN and RAF over the development and control of naval aviation blighted the inter-war period, and was only resolved on the eve of war. Attention focuses on the aircraft types that were employed, very much through the eyes of those that flew or maintained them. Some designs were infinitely better suited to carrier work than others. Another strand of the chapter considers the various types of small carriers employed, including escort carriers and Merchant Aircraft Carriers (MAC ships), whose contribution has been overshadowed by that of larger, famous carriers, such as HMS Ark Royal.

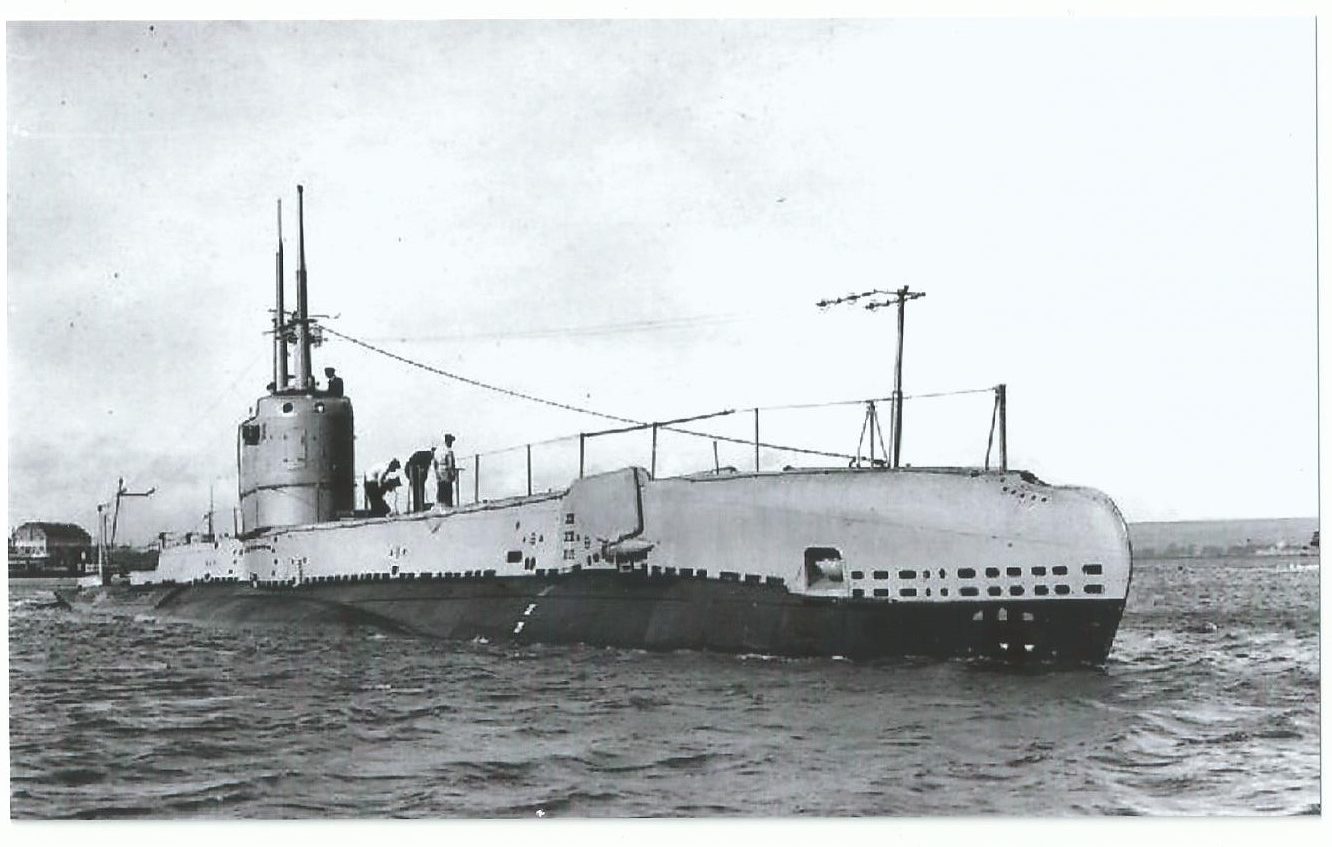

Aspects of underwater warfare are highlighted in chapter three, including the role of submariners and Charioteers. Contrary to the popular view, not all submariners were volunteers, although many were. The chapter considers why men volunteered, aspects of their training, and conditions aboard wartime submarines. Veterans talk of the intense comradeship they enjoyed, as the different branches of the navy felt closer on a submarine than aboard other vessels. There was an overarching atmosphere of stealth during operations, plus fear at being detected by the enemy, when a submarine risked being depth charged, typically a nerve-wracking and frightening experience.

Contrastingly, a Chariot was a form of two-man torpedo that could be steered to a target by two frogmen who sat astride it, and then placed an explosive charge on the target. They had limited range, and as the book demonstrates were employed with varying degrees of success. Divers similarly had important work to perform, notably by clearing obstacles.

To complement underwater warfare, anti-submarine warfare is also discussed. It was essential in winning the Battle of the Atlantic, and the chapter highlights the experiences of sailors aboard the various types of ships employed in this work, alongside discussion of the technological and tactical advances that they experienced during the war.

Chapter four is based around the experiences of naval personnel and merchant seamen on convoys. These were a significant means of countering U-boats, especially in the Atlantic, and required a high degree of skill and seamanship, both from escorts and merchantmen constantly trying to maintain station. Organisation was important, as co-ordination between the navy and merchantmen, wasn’t always as smooth as it could have been. In this regard the role of ‘Convoy Commodores’ was vital. These men, usually retired senior naval officers, were instrumental in guiding convoys towards their destinations. Another key issue was finding suitable ships to act as escorts. Initially, there simply weren’t enough available, but as the war progressed specially designated escort groups evolved that were worked up to a high standard. Equally, in the Artic and Mediterranean, convoys formed major naval operations, and as the book shows many aboard naval and merchant vessels experienced intensive action on convoys in these theatres.

Chapter five concentrates on amphibious warfare, a major undertaking for the Allies in Europe, the Mediterranean and Far East. Notably, Operation Neptune, the naval component of D-Day, was predominantly a Royal Navy affair. Yet, when the war started, the navy hadn’t the men, craft, or doctrine necessary to prosecute large-scale amphibious operations. This capability had to be developed during the war, and was heavily reliant on RNVR officers and HO personnel, many of whom manned landing craft, and didn’t necessarily have any natural aptitude as sailors.

Discipline and morale feature in chapter six. Definitions of morale tend to cite esprit de corps as being integral to it. While this was true, morale was in fact a more nuanced and complex issue. A variety of issues enabled men and women to cope with war, ranging from leave arrangements, to access to material factors such as food, mail, alcohol, tobacco and sex. Inextricably linked with morale was discipline, albeit there could be differences depending on the type of ship in which an individual served. Another part of the chapter illustrates that much wartime naval life revolved around various shore establishments, especially for the majority of Wrens.

Finally, chapter seven discusses experiences of demobilisation, the post-war situation, and provides space for reflections by former wartime naval personnel and merchant seamen from a variety of backgrounds. Today, owing to the passage of time, the numbers of Second World War veterans still alive to tell their stories is sadly dwindling. Hopefully, this book not only proves interesting and informative, but also forms a fitting tribute to those men and women who endured the war at sea, 1939-1945.

‘Naval Eyewitnesses: The Experience of War 1939-1945’ will be published by Pen and Sword Ltd on 30th October 2022.

The book draws upon the personal testimony of wartime sailors and merchant seamen, notably from the oral history collections of the Imperial War Museum and Second World War Experience Centre. During the war the Royal Navy was compelled to absorb large numbers of reservists and ‘Hostilities Only’ (HO personnel). These individuals went on to serve on a bewildering variety of warships and smaller craft or even work in hazardous areas such as mine and bomb disposal. According to the distinguished naval historian, Eric J. Grove, total strength was over 863,000 by mid-1944, including 72,000 members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, better known as the Wrens. Although they didn’t go to sea, Wrens similarly performed a wide variety of tasks.

Many of the men and women quoted in the book developed a deep attachment to the Senior Service, and even enjoyed aspects of their service, despite the privations of wartime. However, the war at sea, was equally as brutal and stressful for those participating in it as the war on land or in the air. British naval casualties for the entire war were 1,525 ships of all types lost, equating to over two million tons of shipping, and over 50,000 personnel killed, many from the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR).

A further 28,000 seafarers aboard British merchant ships were killed, and thousands more died from wounds suffered during their war service or in accidents. Equally as significant was the loss of 4,800 merchant ships, equating to 21.2 million tons. Had the supply of food, raw materials, and armaments from overseas been severed, then it is unlikely that Britain would have been able to continue the war. Merchantmen were also important during the various amphibious operations embarked upon by the Allies, as the war gradually shifted towards the offensive. During Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, for example, around half a million tons of shipping was assembled, including fourteen British hospital ships.

The book is arranged into thematically based chapters. Chapter one deals with life aboard capital ships, such as battleships, and contrasts this with the conditions experienced by sailors aboard smaller vessels, including destroyers, mine sweepers and motor torpedo boats.

Naval aviation and aircraft carriers are covered in the second chapter. The Fleet Air Arm had its own strong identity, but it was deeply unfortunate that tension between the RN and RAF over the development and control of naval aviation blighted the inter-war period, and was only resolved on the eve of war. Attention focuses on the aircraft types that were employed, very much through the eyes of those that flew or maintained them. Some designs were infinitely better suited to carrier work than others. Another strand of the chapter considers the various types of small carriers employed, including escort carriers and Merchant Aircraft Carriers (MAC ships), whose contribution has been overshadowed by that of larger, famous carriers, such as HMS Ark Royal.

Aspects of underwater warfare are highlighted in chapter three, including the role of submariners and Charioteers. Contrary to the popular view, not all submariners were volunteers, although many were. The chapter considers why men volunteered, aspects of their training, and conditions aboard wartime submarines. Veterans talk of the intense comradeship they enjoyed, as the different branches of the navy felt closer on a submarine than aboard other vessels. There was an overarching atmosphere of stealth during operations, plus fear at being detected by the enemy, when a submarine risked being depth charged, typically a nerve-wracking and frightening experience.

Contrastingly, a Chariot was a form of two-man torpedo that could be steered to a target by two frogmen who sat astride it, and then placed an explosive charge on the target. They had limited range, and as the book demonstrates were employed with varying degrees of success. Divers similarly had important work to perform, notably by clearing obstacles.

To complement underwater warfare, anti-submarine warfare is also discussed. It was essential in winning the Battle of the Atlantic, and the chapter highlights the experiences of sailors aboard the various types of ships employed in this work, alongside discussion of the technological and tactical advances that they experienced during the war.

Chapter four is based around the experiences of naval personnel and merchant seamen on convoys. These were a significant means of countering U-boats, especially in the Atlantic, and required a high degree of skill and seamanship, both from escorts and merchantmen constantly trying to maintain station. Organisation was important, as co-ordination between the navy and merchantmen, wasn’t always as smooth as it could have been. In this regard the role of ‘Convoy Commodores’ was vital. These men, usually retired senior naval officers, were instrumental in guiding convoys towards their destinations. Another key issue was finding suitable ships to act as escorts. Initially, there simply weren’t enough available, but as the war progressed specially designated escort groups evolved that were worked up to a high standard. Equally, in the Artic and Mediterranean, convoys formed major naval operations, and as the book shows many aboard naval and merchant vessels experienced intensive action on convoys in these theatres.

Chapter five concentrates on amphibious warfare, a major undertaking for the Allies in Europe, the Mediterranean and Far East. Notably, Operation Neptune, the naval component of D-Day, was predominantly a Royal Navy affair. Yet, when the war started, the navy hadn’t the men, craft, or doctrine necessary to prosecute large-scale amphibious operations. This capability had to be developed during the war, and was heavily reliant on RNVR officers and HO personnel, many of whom manned landing craft, and didn’t necessarily have any natural aptitude as sailors.

Discipline and morale feature in chapter six. Definitions of morale tend to cite esprit de corps as being integral to it. While this was true, morale was in fact a more nuanced and complex issue. A variety of issues enabled men and women to cope with war, ranging from leave arrangements, to access to material factors such as food, mail, alcohol, tobacco and sex. Inextricably linked with morale was discipline, albeit there could be differences depending on the type of ship in which an individual served. Another part of the chapter illustrates that much wartime naval life revolved around various shore establishments, especially for the majority of Wrens.

Finally, chapter seven discusses experiences of demobilisation, the post-war situation, and provides space for reflections by former wartime naval personnel and merchant seamen from a variety of backgrounds. Today, owing to the passage of time, the numbers of Second World War veterans still alive to tell their stories is sadly dwindling. Hopefully, this book not only proves interesting and informative, but also forms a fitting tribute to those men and women who endured the war at sea, 1939-1945.

Photo credits: David Smith (Ex-RN).

‘Naval Eyewitnesses: The Experience of War 1939-1945’ will be published by Pen and Sword Ltd on 30th October 2022.