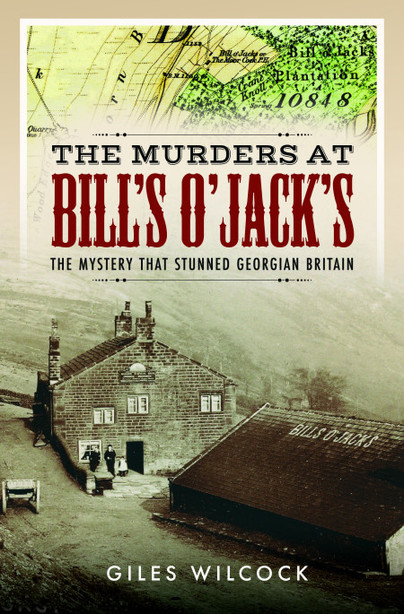

Author Guest Post: Giles Wilcock

The Murders at Bill’s O’Jack’s

One quiet Tuesday morning in spring 1832, a 12-year-old girl called Amelia Winterbottom made her way up the steep hill out of Greenfield, a small village in Saddleworth on the western edge of the Pennines. After a two-mile walk, she reached the home of her grandfather. He was an 85-year-old man called William Bradbury, better known locally as ‘Bill o’Jack’s’, which meant William, son of Jack. He ran an isolated public house — officially called the Cherry Tree but widely called ‘Bill’s o’Jack’s’ after its proprietor — half-way up a picturesque valley offering spectacular views but few signs of civilisation. His nearest neighbour was half-a-mile down the hill; the road continued another half-mile up the hill before turning east to cross Saddleworth Moor. But William did not live alone: his 47-year-old son Thomas lived with him, helping to run the business.

Amelia had been sent on an errand by her mother to collect some yeast from her grandfather. However, when she reached the door, there were no signs of life other than beer brewing outside. She called for her grandfather but received no reply. The door was unlocked, so she went inside. Ahead of her were the stairs to the upper floor, but in the darkened entrance passageway perhaps she didn’t see the bloody footprints on the steps, nor the handprints on the wall. Turning to her right, she went into the main living area of the house.

The scene that greeted her must have stayed with her for the rest of her life.

The entire room — floor, walls and furniture — was covered with blood: some lay congealing in large pools, the rest was splattered on every surface. Lying face-down in the centre of this carnage was a man later identified as Thomas Bradbury, but Amelia did not recognise her uncle, as he was so disfigured. He had been beaten almost to death, and blood was pouring from wounds in his head. Guarding him was a dog, which growled as Amelia entered the room. The terrified girl reached out to touch the man, at which the dog began barking and moved to attack her. This was too much, and she fled in panic out of the house and back down the hill in the direction of her home in the village. When she came to the next house — a cottage known as Binn Green — she told the horrified residents of a man bleeding to death on the floor of her grandfather’s house.

The head of the household, James Whitehead hurried up the road to Bill’s o’Jack’s to see for himself. Whitehead was able to calm the dog, which he recognised as belonging to William Bradbury, but when he examined the man on the floor, he too failed to recognise the swollen and bruised face; the injured man groaned but gave no indication of consciousness. Hearing noises from the room above, Whitehead cautiously climbed the blood-stained stairs, to discover William Bradbury lying in his bed, severely injured and only able to groan. Whitehead asked him who had done this. Bradbury could only mutter what sounded to Whitehead ‘The Pats’, which he took to mean Irishmen, and he immediately assumed that the man injured downstairs was one of the attackers.

Only when the local doctor was summoned was the man identified as Thomas Bradbury. Thomas had a doubly fractured skull and died a few hours later, as a growing number of people gathered around the house to hear the latest news. His father lingered until the early hours of the following morning but at his age, the multiple injuries and broken bones were simply too great to allow for recovery and he too died.

Unsurprisingly, the double murder caused a sensation in Saddleworth and — thanks to newspapers that eagerly reprinted any stories that became available — throughout England. Crowds of people flocked to see the crime scene to inspect for themselves the bloody walls and floors, the battered and stained murder weapons that had been discovered in the house and — until the burial of the two Bradburys the following week — the bodies themselves. A combination of the isolated setting, the spectacular surrounding scenery, the nature of the crime’s discovery and the macabre nature of the murder room meant that the Bill’s o’Jack’s murders seized the imagination.

However, this was no short-term fascination. Two other factors sustained interest in the story for years. The first was the identities of the two victims. Very little is known today about William and Thomas Bradbury except for the fact of their deaths, although a stream of semi-legendary stories of doubtful provenance emerged over the following hundred years. But it seems certain that neither man was a model citizen. William, for example, ran an illegal establishment for a time on the site of Bill’s o’Jack’s without a licence and had a messy dispute with his landlord not long before the murders. As for Thomas, he seems to have been a tough character who was involved in altercations with various people, apparently had an interest in local politics, and might have had a semi-official position as a kind of gamekeeper, which he used to terrorise and exploit anyone wanting to use Saddleworth Moor (which at the time was technically common land). He was also a known poacher and might have had at least one extra-marital affair that resulted in a child being born; he certainly was not living with his wife at the time of his murder. There could have been many people who were not sorry to see him dead.

The second factor was that the murders were never solved. When a friend of Thomas Bradbury had been with him the night before he died, the pair had met a suspicious trio of whom Thomas seemed wary and who might have been Irish workers. These men became the main suspects, resulting in a frenzied hunt for anyone who even ‘looked’ Irish. One man was held in custody but released when it became obvious he had nothing to do with the murders; two local poachers were also briefly detained but no-one was ever charged. None of several supposed confessions made in following twenty years stood up to scrutiny. Later in the century, a growing taste for ‘detective fiction’ doubtless increased the intrigue around the identity (or identities) of whoever was responsible.

Therefore, the Bill’s o’Jack’s murders remained a subject of great fascination, kept alive in countless newspaper articles and commemorated in poetry, several plays and at least three fictionalised accounts. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, various proposals were made regarding who might have been responsible, not least in 1871 when a book called Saddleworth Sketches revisited the story in detail. It provided some ‘new’ information (in reality, little more than gossip) that reframed all subsequent discussion of the murders, not necessarily for the better. Successive landlords of Bill’s o’Jack’s (later renamed The Moorcock) continued to fan the flames of publicity, even selling souvenirs, until it was eventually closed and demolished in 1937.

Only the Moors Murders of the 1960s finally eclipsed the Bill’s o’Jack’s murders in notoriety, and even today the story is remembered in parts of Saddleworth. Although there is no chance that it will ever be solved now, the tale gives a fascinating insight into a very different time.

Order your copy here.