Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

Thursday, 31 October 1940: The Final Curtain Falls

In previous blogs we have explored the significance of certain dates during the Battle of Britain, including an evidenced argument that the Battle actually began on 2 July 1940, when Hitler first expressed his intention to invade Britain, and ended on 12 October 1940, when he called off this hazardous undertaking completely – thereby challenging the official dates of 10 July 1940 – 31 October 1940.

As we have seen, the German daylight bomber offensive was defeated on 30 September 1940, the last major daylight attack occurring a week later. Afterwards, the daylight fighting featured high-altitude fighter sweeps and heavily escorted high-altitude fighter bomber raids, largely aimed at London, which continued not only beyond 12 October 1940, but also 31 October 1940. Indeed, the fighter forces of both sides clashed frequently until the winter weather in February 1941.

The German tactics of strong daylight fighter sweeps and high-altitude fighter-bomber attacks throughout October 1940, however, represented a sensible strategy. Although such indiscriminate light bombing could not bring about Britain’s defeat, these raids were nonetheless inspired. While the move to make one Staffel in every Gruppe a Jabo unit was unpopular with the German fighter pilots themselves, the fighter-bomber was an exceptionally dangerous weapon – as the Allies would later demonstrate to devastating effect during the second half of the war.

Single-engine fighter-bombers were fast and could attack at any altitude, from 30,000 feet to ground-level, their presence within a formation of single-engine aircraft being impossible for RDF or the Observer Corps to detect – and once bombs had been dropped the Jabo reverted to being a pure fighter. The high-altitude nature of these raids also meant that reacting to them several times a day, or more, was physically exhausting, especially in unpressurised cockpits. Moreover, the attacks by lone Ju 88s on days of bad weather ensured little rest for the aircrew of Fighter Command.

Equally, though, these were difficult missions for the Jabo pilots especially, owing to a lack of training and given that the Me 109 had no bomb-sighting apparatus, only lines on the side panels of the pilot’s canopy, which if brought in line with the horizon indicated whether the aircraft was at an angle of 40°, 50°, 60° or 70°. The actual bombing, therefore, relied upon guesswork, and it was impossible to guarantee hitting a specific target from high-altitude. Little of any military value, therefore, was achieved during this final phase, and nor did the British economy unduly suffer – but these nuisance attacks got Fighter Command off the ground, to be engaged by German fighters.

These raids, though, were incomparable to the sorties of Allied fighter-bombers later in the war, which were directly supporting the advancing army, usually at low-level, because of that and one other vital fact: the Allied fighters enjoyed total aerial supremacy, which the Luftwaffe never did over Britain in 1940. Certainly on particular days the tide of battle swung well in the enemy’s favour – but the fact remains that, overall, Fighter Command never lost control of the air.

Flying Officer Frank Brinsden, a Spitfire pilot of 19 Squadron at Fowlmere in 12 Group commented that as follows: ‘I do not believe that many of us at squadron pilot level realized that we were engaged in a full-scale battle, nor how important the outcome would be if we lost. Again, in retrospect, intelligence briefing was sadly lacking in its scope.’

Flight Sergeant George ‘Grumpy’ Unwin DFM, the ‘High Priest’ of 19 Squadron, added that: ‘At the time I felt that we of Fighter Command had done nothing out of the ordinary. I had been trained for the job and luckily had a lot of experience. I was always most disappointed if the Squadron got into a scrap when I was off duty, and this applied to all the pilots I knew. It was only after the event that I realised how serious defeat would have been, but then, without being big-headed, we never ever considered being beaten, it was just not possible in our eyes, this simply was our outlook. As we lost pilots and aircraft, replacements were forthcoming. We were never at much below full strength. Of course, the new pilots were inexperienced, but so were the German replacements.’

Air Vice-Marshal Park, the ‘Defender of London’, later reported on this final phase: ‘I wish to pay high tribute to the fine offensive spirit of pilots in all squadrons during the past two months of difficult fighting. During the second phase of operations, the morale of our pilots has been severely tested, because the enemy has had a great advantage in superior performance at high altitude in the Fighter versus Fighter battle. When well-led, however, our pilots have out-fought the enemy at all heights. With few exceptions. Squadron commanders and flight commanders have quickly adapted themselves to the changing tactics of the enemy.

‘The enemy’s superior numbers enable him to throw our fighter forces on the defensive, resulting in the majority of the fighting in the past three months taking place either over British territory or close to our shores. Our constant aim, however, has been to intercept the enemy as far forward as possible and make him shed his bombs harmlessly in open country or in the sea. The aim of all squadrons in the Group now is to inflict such heavy punishment that the enemy will find it too hot to send his fighter patrols or daylight raids inland over home territory, and our pilots will not be satisfied until the air over the Homeland is again free of the German Air Force.’

As the rain lashed down on Whitehall on that last day of October 1940, the Prime Minister chaired a meeting of the Government Defence Committee deep underground in the Cabinet War Rooms. It was agreed that the invasion crisis had passed, the future threat of it ‘remote’, and that, therefore, with overseas military commitments in mind, Britain’s defences should now be stood-down from their alerted state of ‘Immediate Readiness’.

Officially, so far as the Air Ministry was concerned, the Battle of Britain was at last over.

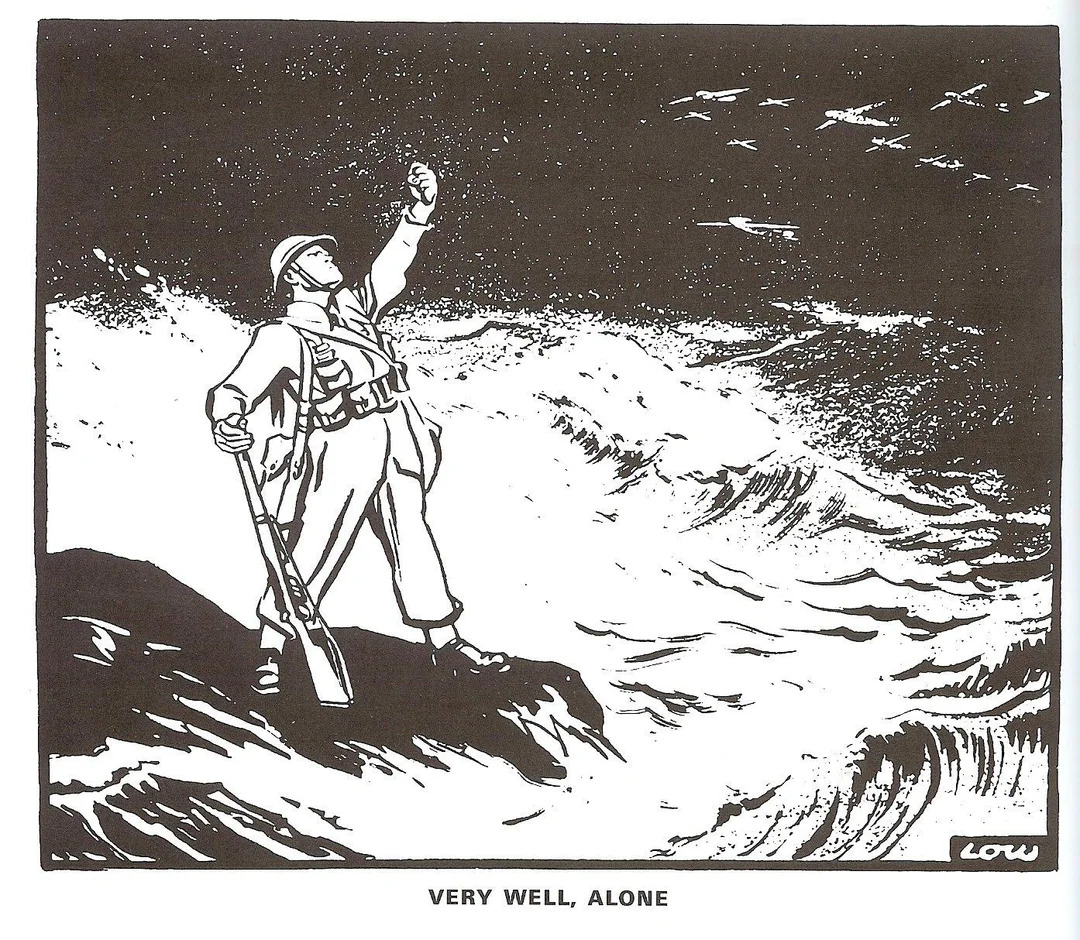

Why was this so significant? Simply because Britain, the only free western democracy, remained in the war and the only base in western Europe from which the liberation of enemy-occupied Europe could one day be launched. Some have argued that the most important battle of the Second World War was the Battle of the Atlantic; indeed, Churchill wrote that the sea battle was the only thing that ‘worried’ him. Nonetheless, to suggest that the Battle of the Atlantic was more important than the Battle of Britain completely misses the obvious and all-important point: had Britain fallen in 1940, there would have been no other battles. Hitler would have marched into Britain and that would have been an end to it: no Battle of the Atlantic, no Strategic Bombing Campaign, nothing. Just Nazi oppression.

Arguably, then, when Hitler turned away from Operation Seelöwe on 12 October 1940, that was the day Germany lost the Second World War. Victory in the Battle of Britain essentially belongs to the men and women of the RAF – not just Fighter Command, but also Bomber and Coastal Commands, and, indeed, even pilots from Training Command and ferry units, some of whom gave their lives in the defence of Britain that tumultuous summer and autumn.

On the ground, the Home Front was steadfast, as were the other defences, the emergency services, and, of course, the Royal Navy, of which the Germans were afraid. The Battle of Britain is a massive story, and victory belongs to all – as is evidenced and explored in my one-million-word official history in eight volumes for the Battle of Britain Memorial Trust and National Memorial to The Few, published by Pen & Sword.

To that victory, and those responsible for it, we will always owe an immeasurable debt – which must never be forgotten.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.