Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

Saturday, 7 September 1940: The Bombing of London

On the night of 24/25 August 1940, German bombers, intending to attack Rochester and Thameshaven, unintentionally bombed central London – contrary to Hitler’s express orders that attacks on the British capital were prohibited without his personal permission (see Airfields Under Attack: 19 August 1940 – 6 September 1940, Volume 4). Even Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, Hitler’s deputy and chief of the Luftwaffe, had overstepped the mark on 19 August 1940 in his Karinhall memorandum, declaring that he had reserved the personal right to exclusively order raids on London and Liverpool. The Reichsmarschall was furious when he learned that bombs had then been dropped on the British capital without his authority, immediately requiring reports identifying the crews responsible – promising that each aircraft captain involved would be punished and ‘posted to infantry regiments’.

Churchill was determined to ‘return the compliment … upon Berlin’, and so that next night saw Bomber Command send Hampdens and Wellingtons to Berlin. The target, however, was covered in cloud: bombs largely fell harmlessly in countryside South of the German capital, although two people were injured in a Berlin suburb and a chalet was destroyed. The effect on German morale, though, was shocking: Göring had assured the German Volk that such a thing would never happen, that it was just not possible for the RAF to bomb Germany; the people believed him. Now, they were left stunned and disillusioned.

Hitler too was furious. On 4 September 1940, he addressed a gathering at the launch of the Winterhilfe campaign at the Sportspalast in Berlin-Schöneberg. RAF airmen, he said, had not the courage or skill required to fly across the North Sea and bomb Germany by daylight, but instead did so by night, protected by a cloak of darkness, their bombs dropped indiscriminately on residential areas, farmhouses and villages.

The Führer continued: ‘You will understand that we must now reply, night for night and with increasing force. And if the British air force drops two, three or four thousand kilos of bombs, then we will drop 150,000, 180,000, 230,000, 300,000 or 400,000 kilos, or more, in one night. If they declare that they will attack our cities on a large-scale, we will erase theirs! We will put a stop to the game of these night-pirates, as God is our witness.’

At a stage in the Battle of Britain when the Luftwaffe was actually making significant progress in terms of wearing down Fighter Command, owing to the bombing of Berlin and the loss of prestige for Hitler that entailed, the Führer, as Churchill had rightly anticipated, now ordered Göring to retaliate and attack London itself.

Across the Channel, the OKL’s plan for the surprise attack on London – codenamed Loge, after the Norse fire god – starting on 7 September 1940, was as follows: ‘Whilst Luftflotte 3 operates at night, during the day Luftflotte 2, using single and twin-engined fighter formations at the same time, will carry out attacks until the dock installations and the city’s power and other supplies are destroyed. The city is divided into two target areas: Target Area A comprises East London with its extensive dock installations, whilst Target Area B covers West London with the city’s power supply plants and supply installations.’

Although blissfully unaware of it, Londoners were about to endure the capital’s worst ordeal since the Black Death (1346 – 1353) and Great Fire (1666). The Battle of London was about to begin, a contest between the resolve of unarmed civilians against high explosive and incendiary bombs, and air mines, a battle propelling the fire, police, ambulance and medical services into the van of the Home Front – and many an unlikely hero would emerge from the impending carnage.

The morning of Saturday, 7 September 1940 was surprisingly quiet, Eastender Violet Regan remembering it as, ‘Beautiful. The warm sun shone from a clear blue sky onto the little streets of Cubitt Town, Isle of Dogs. No premonition of the terrible ordeal that was to be endured for the rest of the day and night occurred to me as I went about my usual chores’.

It was also ominously quiet in Air Vice-Marshal Park’s underground Operations Room at 11 Group HQ, Uxbridge.

Across the Channel, Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring’s staff officers had been busy – and the detailed operational orders decided for this first major attack on Loge by I and II Fliegerkorps was about to become reality. At 1700 hrs (BST) the initial attack was to be made by one Kampfgeschwader of Fliegerkorps II, the purpose being to ‘force English fighters into the air so that they will have reached end of their endurance at time of main attack’. That main bombardment, by II Fliegerkorps was to begin forty minutes later, and five minutes afterwards elements of I Fliegerkorps, reinforced by II Fliegerkorps’ KG30, would continue the destruction. For the main attack, the Ju 88s of KG30 and II/KG76 would be positioned on the right, KG1’s He 111s in the centre, and Do 17s of I and III/KG76 on the left.

Determined to keep his bomber losses to a minimum, Reichsmarschall Göring deployed 648 fighters, shackling one Jagdgeschwader to each Kampfgeschwader: JG26 for KG30, JG54 for KG1 and KG27 for KG76; somewhat optimistically, the Me 110s of ZG76 were tasked with clearing ‘the air of enemy fighters of I Fliegerkorps’ targets, thereby covering the attack and retreat of bomber formations’. The fighters and bombers were to rendezvous over the French coast. Because the Me 109s were operating at the extremity of their range, there was no time to waste and the bombers were to fly directly to their targets, KG30’s formation staggered between 15,000 – 17,000 feet, KG1 18,000 – 20,000 feet, and KG76 15,000 – 17,000 feet, this intended to ‘provide maximum concentration of the attacking force’.

Having bombed, the enemy crews were briefed to make a starboard turn before returning to the Kentish coast via Maidstone and Dymchurch, returning to France across the Channel, only leaving the fighters over the Pas-de-Calais. After dark, the Germans planned no respite for the defenders or beleaguered Londoners: night-bombers, mainly from Luftflotte 3, guided to their targets by Loge’s fires, were to continue the assault.

The ‘main objective of the operation’, the Order concluded, was ‘to prove that the Luftwaffe can achieve this’ – evidencing that doubt existed in certain quarters of the OKW. Reichsmarschall Göring was now inspired by the new plan, arriving in the Pas-de-Calais on his personal, luxurious train, Asia, to enthusiastically take personal command of the attack on London.

At 1530 hrs, RDF began reporting the assembly of German formations over the Pas-de-Calais. Fifteen minutes later a small German force, which had been patrolling the Dover Strait, swept over New Romney. By 1555 hrs, one enemy formation was over Cap Gris Nez, a second was ten miles off Dunkirk and heading for the Thames Estuary, and a third was flying West, between St Omer and Boulogne. The estimated total of aircraft involved suggested that this was the biggest challenge Fighter Command had faced so far. Naturally, the enemy’s target was assumed to yet again be 11 Group’s airfields – so RAF squadrons were deployed accordingly.

On the cliffs at Cap Gris Nez, Göring, Kesselring, General Bruno Loerzer, commander of Fliegerkorps II, and various high-ranking staff officers watched excitedly as 348 bombers escorted by 617 fighters passed overhead. This massive formation of nearly 1,000 aircraft occupied a staggering twenty-mile wide front, stepped up a mile-and-a half high and spread out over 800 square miles. The sky had indeed darkened, the noise deafening – and, as the illustrious Reichsmarschall said, ‘If we lose now, we deserve to have our arses kicked’.

Looking up at the Luftwaffe’s might roaring towards London, wave after wave, it was no doubt difficult to comprehend that Germany could lose. Göring was in his element, ecstatic in what, he believed, would be recorded by history as his triumphal hour.

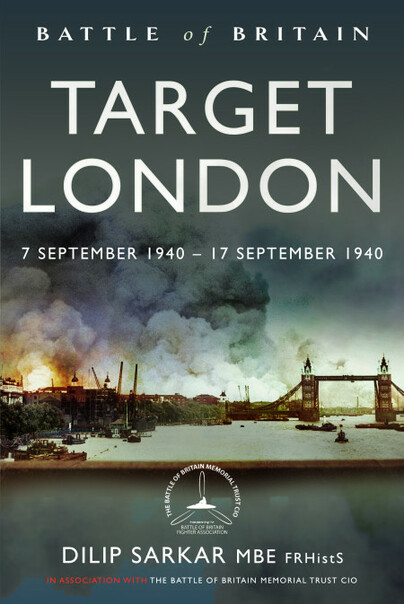

No.11 Group was caught out, the enemy formations penetrating to the capital, warning sirens blaring over London at 1633 hrs. The events of that fateful day, both in the air and on the ground, are re-counted in detail, from a 360 perspective, minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow, the narrative proliferated with first-hand accounts, in my Target London: 7 September 1940 – 17 September 1940, this being the fifth of the eight-volume, one-million-word official history I have recently completed for The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO and National Memorial to The Few, published by Pen & Sword.

RAF fighters of 10, 11 and 12 Groups intercepted the retiring raiders, this actually being the first time the legless Squadron Leader Douglas Bader led the controversial Duxford Wing into action (which was unsuccessful owing to the 12v Group fighters being bounced whilst climbing). Down below, Londoners proved they could ‘take it’, and foremen bravely fought to bring the fires engulfing the docklands under control. It was now that the Chiefs of Staff, shaken by the enormity of the attack on the capital, issued a simple code word: Cromwell – invasion imminent. The nocturnal attack began at 2010 hrs, lasting until 0430 hrs the following morning, Sperrle’s Luftflotte 3 bombers flying shuttles, back and forth across the Channel.

The attack had been an enormous success: London had been substantially bombarded and Fighter Command had lost twenty-eight fighters destroyed and sixteen more damaged; thirteen pilots had been killed – the highest number since the great battles of 15 August 1940 (also thirteen).

The following morning, Air Vice-Marshal Park – the only RAF High Commander able to fly modern fighters – took-off in his personal Hurricane, ‘OK1’, and, according to his flying logbook, flew from Northolt to Stapleford Tawney airfield, thence to the North Weald Sector station before returning to Northolt via South London. From the vantage point of his fighter’s cockpit, Park could clearly see the damage and destruction wrought by Göring’s unprecedented assault of the previous day. By flying doggedly and directly to their target in close formation, thereby protected by their mutual, withering, cross-fire and hundreds of escorting fighters, the Germans had bludgeoned their way through to and grievously hurt London – which Fighter Command had failed to prevent.

The still burning docklands and East End below was something Park would never forget: ‘It was burning all down the river. It was a horrid sight. But I looked down and said ‘Thank God for that’, because I knew that the Nazis had switched their attack from our fighter stations, thinking they were knocked out. They weren’t, but they were pretty groggy.’

Churchill’s predication that by bombing Berlin, Hitler would retaliate and bomb London – thereby saving the airfields from further damage and, having a longer flight to their target, provide Fighter Command with more opportunities to intercept, had been grimly proved correct. The fighter stations were not, as Park said, ‘knocked out’, but as he also commented, ‘they were pretty groggy’. For all the pain Park felt viewing London’s agony below, he also knew that the enemy’s change of strategy represented a major turning point in the battle – and a reprieve for both his airfields.

Only time would tell what the Germans would do next – but now, the Battle of the Airfields over, Park knew that he faced the greatest challenge yet: the Battle of London.

Order your copy here.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.