Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

Fighter Pilots and Pubs!

Heavy with tobacco smoke and the sweet smell of English ale, the wartime public house – more commonly known as the ‘pub’ – provided an essential social function, a place where local people could come together and relax. Inevitably, from a piano in the bar a nimble-fingered patron played tunes of the day, and doubtless rowdy gatherings of drinkers belted out such popular songs as ‘Roll out the barrel’ and ‘We’ll Meet Again’. Cards, backgammon, and darts were all popular bar games, and, away from their bases, the ‘local’ also provided an essential escape from military life for service men and women – not least RAF fighter pilots…

The personnel of all aerodromes had their favourite pubs nearby, although we must remember that in those days officers would use one place, Non-Commissioned Officers and Other Ranks another; during the Battle of Britain, George Unwin was a Flight Sergeant flying Spitfires with 19 Squadron at Fowlmere, the Duxford satellite, and explained that: –

‘Brian Lane, at first my Flight Commander in “A” Flight and later our Commanding Officer, and I were friends, and flew together many times. We did not, though, ever socialise on the ground because he was an officer and I an NCO. In the air that made no difference but on the ground the service remained socially segregated’.

John Milne was Squadron Leader Lane’s Flight Rigger:-

‘We lowly “erks” (author’s note: RAF slang for groundcrew) used the “Chequers” pub in Fowlmere village, the officers “The Red Lion” at Whittlesford, and never the twain met over a pint’.

In August 1940, ‘A’ Flight of Exeter’s 87 Squadron was deployed to the small airfield at Bibury in Gloucestershire, from where the Hurricanes afforded some protection to the various aircraft factories in the West Country. The pilots quickly took over the ‘Swan Hotel’, in the village, but a particular snapshot indicates that things were more relaxed socially than on 19 and certain other squadrons. One August evening, Flight Lieutenant Ian ‘Widge’ Gleed DFC, the Flight Commander, was pictured standing outside the hotel with four other officer pilots – one of which was reported missing a few days later. The photograph was taken by Sergeant Laurence ‘Rubber’ Thorogood, who later told me that: ‘Out at Bibury, away from the formality of Exeter’s messes, we could be more relaxed and all ranks of our small deployment enjoyed using the “Swan”’.

The Poles of 308 ‘City of Krakow’ Squadron moved to Baginton, near Coventry, in the winter of 1941, working up on Spitfires there, and immediately made the nearby ‘Oak’ inn its unofficial headquarters. Across the road from the pub is the famous ‘Baginton Oak’ tree, from which the pub derives its name, and in February 1941, a group of 308 Squadron’s pilots were pictured around the huge tree after doubtless sinking a few pints across the road – just weeks later, after the Squadron joined No 1 Polish Fighter Wing at RAF Northolt, several of those young men would be killed or missing in action – making the photograph especially poignant.

Polish Spitfire pilot Kazek Budzik flew with various Polish fighter squadrons and recalled that:-

‘It was strange going off to war for an hour or so, then coming back to clean and comfortable living conditions with good food in the Mess. It was strange being shot at one minute then being back in London the next, possibly having a drink in a pub just a short while after escorting bombers to a target in France. People have the impression that we fighter pilots had it easy, but what they fail to consider is that we flew long tours of operational duty. That type of intense flying juxtaposed with good living conditions and a social life actually caused great stress, in its own way, but I don’t think people generally appreciate that’.

For the Poles of No 1 (Polish) Fighter Wing at Northolt, their local was the ‘Target’ – which, like the other pubs mentioned in this piece, is still there but now a McDonald’s restaurant!

Nearby Kenley became home to the Canadian Spitfire Wing, commanded by the English Wing Commander Johnnie Johnson DSO DFC, who would eventually become the RAF’s officially top-scoring fighter pilot of the Second World War – and possessed the true gift of leadership. Amongst Johnnie’s pilots was Hugh Godefroy – later a decorated fighter ace and wing leader himself – who remembered how important a sortie to the pub often was to morale: –

‘In the air, Johnnie Johnson was “Greycap Leader”, cool, commanding, and as aggressive as a bull terrier. But when the sun went down, he didn’t mind being called “Johnnie”. He was one of us. His responses seemed Canadian, pure and simple.” What we need is a piss-up! I’ve had my fill of liver and onions. Monty!”

“Sir!”

“Call the ‘Red Lion’ at Redhill and tell them to kill the bloody fatted calf. We’re on our way. Come on lads, fill up the vans and follow me. Hughie, you’d better come in mine. I may need a second pair of eyes on the way home!”

Chuckling with anticipation, everybody grabbed their caps and piled into the vans. As expected, it was a hair-raising ride. What with the masked headlights and my poor night vision, I didn’t see obstructions until we were almost upon them.

“Get out of the bloody way, you stupid bastard!”, Johnnie would shout, as he suddenly overtook a vehicle.

“Clear the road, the Kenleys are coming!”

“That’s original, Hughie, I rather like that”.

“Look out Johnnie, there’s a man in the middle of the road!”

“Bloody Canadian, you obviously haven’t learned to drive in England yet!”

I was greatly relieved when we pulled in the parking lot of the “Red Lion”.

“There we are – my kingdom for a pint of Guiness!”

To the amusement of most of the regulars we took over. There was plenty of beer, games of darts and skittles. Johnnie, with the help of Walter Conrad, led a singsong around the piano with old favourites like ‘Roll out the Barrel’, ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and the South African Zulu war dance, ‘Hey zinga, zumba. Zumba, zumba’. There was food for those who wanted it: smoked salmon and excellent steak-and-kidney pie.

When the proprietor shouted:

“Time gentlemen, please!” there was a Chorus of:

“A-w-w-w-w-w-!”

“Time gentlemen, for one more for the road!”

“Right you are”, said Johnnie. “OK lads, you’ve ‘ad it. Bottoms up! There’s work to do in the morning”.

I offered to drive.

“What?” said Johnnie. “You drive in your present state of public drunkenness? Not bloody likely! What we need is a sober man at the wheel. Look, some stupid clot has boxed me in. I’ll show the bastard!”

With a crunch, Johnnie backed the van into the car behind, shunting it a good six feet to the rear.

“That’s better. All aboard, chaps!”

When the van was full, we were off in a cloud of dust. But now, with a few pints of ale and a steak-and-kidney pie under my belt, somehow it didn’t seem to matter. After a while, in the dim light of our shielded headlights, I saw half-a-dozen women walking on the right side of the road. With a squeal of tyres, Johnnie slammed on the brakes.

“There they are chaps, same level, 12 o’clock, get into them and don’t let any of them get away!”

Tittering with laughter, Johnnie led us in pursuit of the women who had now broken into a trot. Johnnie caught the hand of a young lady straggler and as he spun her round she butted her cigarette in his left ear.

“O-w-w-w”, he said, “You nasty little bitch!”

The ladies in front stopped, and from their midst we hears a querulous voice say “Nobody calls my daughter a ‘nasty little bitch’. I say, what’s all this in aid of?”

“They’ve got us outnumbered, return to base!”

To the sound of Johnnie’s giggling laughter, we all piled back in the truck again and took off. It was a happy light-hearted evening, full of harmless fun, and in the Johnson tradition punctuated with the unexpected. There wasn’t a man who didn’t waken refreshed and ready to follow him in the morning’.

Close to Redhill was the famous Biggin Hill fighter station, the pilots adopting the nearby ‘White Hart’ at Brasted, a blackout board there being signed in chalk by such aces as the legendary South African Group Captain ‘Sailor’ Malan, Wing Commander Robert Stanford Tuck and many more besides, including Tony Bartley, whose daughter, Teresa McShane, recalled that ‘It was an incredibly important bolt hole for the pilots, who faced death on a regular basis’. The historic blackout board has, cutting a long story short, been preserved and can be seen today at the Shoreham Aircraft Museum.

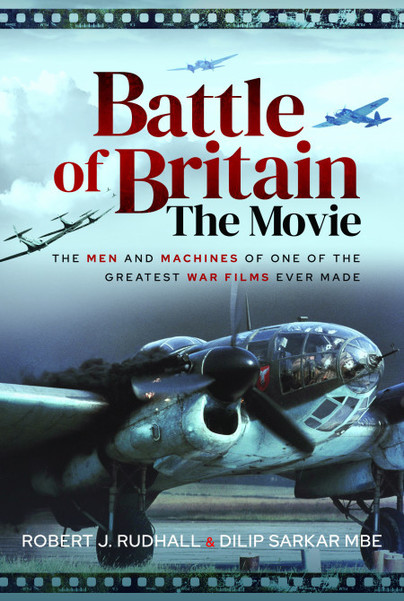

During the Battle of Britain the closest RAF airfield to the Germans across the Channel in France was at Hawkinge, near Folkestone, which today accommodates the Kent Battle of Britain Museum’s vast collection of artefacts. Nearby, at Denton, just South of Canterbury, is the famous ‘Jackdaw Inn’, also well-used by wartime airmen. Unlike the ‘White Hart’, however, the ‘Jackdaw’s’ fame was achieved post-war owing to its use as a location in the 1969 epic film Battle of Britain. With the Home Guard drilling outside, Christopher Plummer, playing ‘Squadron Leader Harvey’, a Canadian, arrives in his green MG to meet his wife, WAAF ‘Section Officer Maggie Harvey’, portrayed by Susannah York. The interior scenes between the two were filmed elsewhere, at ‘The Hoops’ in Bassingbourn, although you would be hard-pushed to tell: the ‘Jackdaw’, although extended, remains a quintessential Kentish pub, boasting an excellent ambience, service, food and drink, the pub displaying various wartime aviation related prints and photographs. In fact, on Saturday 14 and Sunday 15 September 2024, the current licensee, Graham Bevan, is holding a Battle of Britain Beer Festival – at which I will be signing copies of Battle of Britain: The Movie, The Battle of Britain on the Big Screen, and more besides. For further information contact the ‘Jackdaw’ on 01303 844663.

So, the good old ‘local’ undoubtedly provided an important retreat for all during wartime, not least airmen. All of the venues mentioned in this article still exist today, in some cases retaining their original charm. Indeed, perhaps a Battle of Britain themed guide to pubs is a book for a CAMRA enthusiast to consider – and clearly Graham’s Beer Festival at the ‘Jackdaw’ is not to be missed – see you there, mine’s a pint of ‘Spitfire Ale’!

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS, 2024

Dilip Sarkar will also be speaking and signing at The National Memorial to The Few, Capel-le-Ferne, at 12 pm on Sunday 15 September 2024; places are free but limited so please book tickets by emailing enquiries@battleofbritainmemorial.org.

Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.

Kent Battle of Britain Museum.

The Battle of Britain on the Big Screen.

All images Dilip Sarkar Archive.