Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

The Hardest Day: Sunday 18 August 1940

From an operational perspective, Sunday, 18 August 1940 began with Luftwaffe shipping and weather reconnaissance flights over the North Sea. At 0520 hrs, the Hurricanes of 257 Squadron left Debden in Essex to operate from the forward base at Martlesham Heath, from where, at 0622 hrs, ‘A’ Flight’s Yellow Section took off to patrol a southbound convoy off the East coast. Sixty miles south-east of Martlesham, at 3,000 feet, Yellow Leader, Pilot Officer Arthur Cochrane, ‘… chased a Do 17 and had a combat with it. The enemy bomber went straight up into the air and its port undercarriage fell’ (ORB). Cochrane reported that ‘During his break-away there was a very loud bang and I thought my machine was hit. After coming out of his break-away, the E/A was nowhere to be seen. I then set course for land and base’. Cochrane’s Hurricane was actually undamaged; the Do 17 was considered probably destroyed, although more likely it regained base, damaged.

The next three hours were ominously quiet. Then, between 1100 hrs and 1130 hrs, various lone snoopers reconnoitred 11 Group’s airfields. At 0825 hrs, Squadron Leader ‘Prof’ Leathart had led his 54 Squadron from Hornchurch to the forward base at Manston, from where, at 1054 hrs, the Spitfires scrambled ‘to investigate unidentified aircraft flying at 25,000 feet north-east of aerodrome. Five of the pilots climbed to 25,000 feet and saw machine 8,000 feet above them. They engaged this machine, identified as an Me 110’ (ORB). Flight Lieutenant George Gribble and Pilot Officer Colin Gray were first to attack, Gray temporarily setting both engines ablaze and Gribble ‘holing the fuselage’.

Flight Sergeant Phillip Tew then attacked, the Me 110’s engine again catching fire whilst the aircraft dived steeply for France. Pilot Officer William Hopkin was fourth into the attack, knocking pieces of the stricken enemy aircraft, and finally Sergeant John Norwell opened fire at sea-level, pulling out of his dive ‘only a very few feet above the water’. The Me 110 was last seen ‘fully ablaze’, but was not seen to crash into the water. The Me 110, of 7(F)/LG2, was shared between the pilots concerned and accredited as destroyed – which indeed it was: Oberleutnant Arnold Werdin was reported missing, and Oberfeldwebel Hans Knopf was killed. So perished the first victims of what the late British historian Dr Alfred Price famously called ‘The Hardest Day’ – and what was about to follow was anything other than quiet.

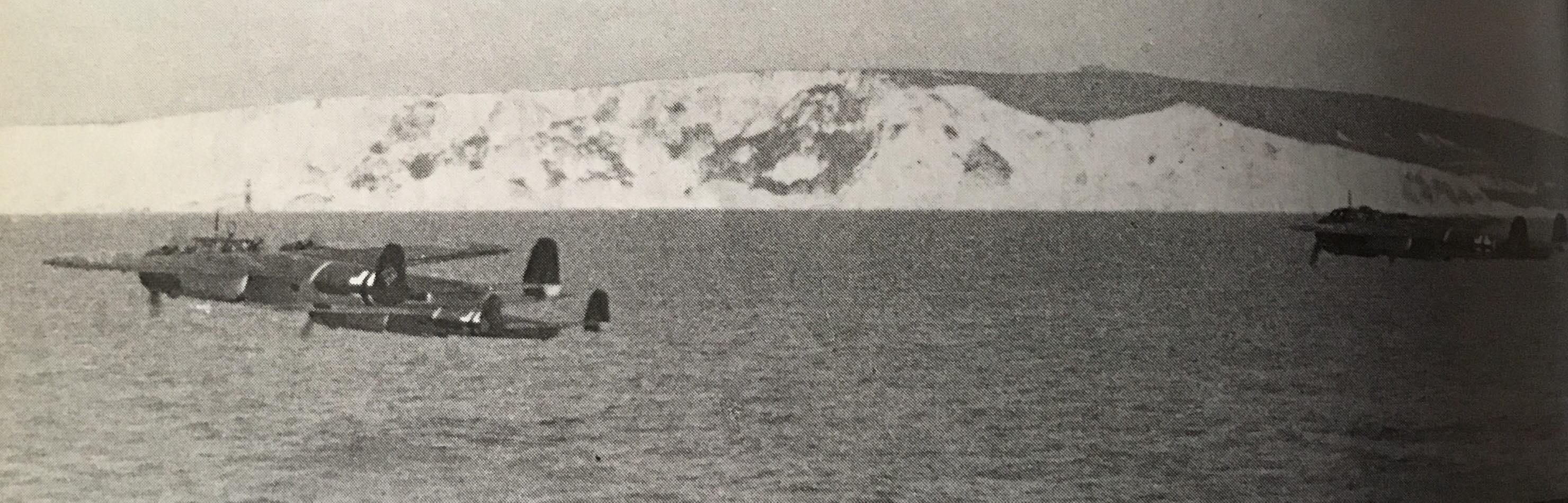

With the weather set fair, Luftflotte 2’s HQ in Brussels signalled a flurry of executive orders for the day’s raids. KG1, based around Amiens, was to attack Biggin Hill with sixty He 111s. Kenley was to be hit in audacious fashion: twelve Ju 88s of Major Friedrich Möericke’s Creil-based II/KG76, and a further twenty-seven Do 17s of Major Theodore Schweitzer’s I/KG76, operating from Beauvais, and Möericke’s II/KG76 were to cross the Kentish coast over Dover and bomb Kenley from high altitude. Then, nine Do 17s of Hauptmann Joachim Roth’s 9/KG76, based at Cormieilles-en-Vexin, North of Paris, were to cross the Channel at zero feet before making landfall at Cuckmere Haven, just West of Beachy Head in East Sussex, then hedge-hopping north-east a few miles to Burgess Hill and turning due North for Kenley – some sixty miles inland.

The Kenley plan was comparatively complex. First, the Ju 88s of II/KG76 were approach at high altitude before dive-bombing hangars and other airfield buildings. Then, the heavily escorted high-flying Do 17s of I and II/KG76 would crater the runway and destroy the airfield’s defences. Finally, 9/KG76 would appear low and fast, in the first such zero-feet raid on England, to monopolise of the destructive chaos already achieved to reduce whatever airfield installations remained to rubble. Conversely, Biggin Hill was simply to be attacked by successive waves of sixty heavily escorted He 111s of Generalmajor Karl Angerstein’s KG1 ‘Hindenburg’, based at Rosiéres-en-Santerre and Montdidier, near Amiens, which would, it was hoped, completely destroy the Station.

Although the low-flying 9/KG76 Do 17s were unescorted, relying upon guile and surprise, the remaining bomber formations were to be closely protected by JG51, 52 and 54, and ZG26. From the fighter pilots’ perspective, however, the best mission was given to JG3 and JG26 – a Freie Jagd comprising sixty Me 109s sweeping ahead of the main bomber formations bound for Kenley and Biggin Hill. Unlike many airfields previously attacked, both Kenley and Biggin Hill were Sector Stations, accommodating vital sector operations rooms – although, remarkably, this still remained unknown by Luftwaffe intelligence. Nonetheless, this great raid could potentially deliver a body-blow to London’s defensive ring.

The subsequent fighting is deconstructed and explored, minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow, in Attack of The Eagles: 13 August 1940 – 18 August 1940, which is the third of the eight-volume official history I have recently completed, in one-million words, for The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust and National Memorial to The Few, published by Pen & Sword.

Suffice it to say here that although great damage was caused, the complex Kenley plan misfired: when 9/KG76’s low-flying Dorniers arrived, instead of finding the aerodrome already battered by dive-bombers and high-flying raiders, the target was intact. Inevitably, the Do 17s became the focus of Kenley’s defences: four 40-mm Bofors guns rapid firing their eight-round magazines, whilst the heavier pair of 3-inch guns pumped rounds out at a slower rate. The German air gunners responded and the whole airfield became a maelstrom of shot and shell, a cacophony of gun fire and explosions. The bombers were attacked by all means, including the frightening Parachute and Cable, which snaked up from the far side of the airfield, and the Hurricanes of 111 Squadron. Carnage ensued, and Kenley suffered heavy damage.

At Biggin Hill, KG1 cratered the runway, the WAAF Sergeant Joan Mortimer bravely marking the position of UXBs to assist returning pilots – for which feat of valour the Military Medal was later awarded. Croydon airfield was also hit, the whole of south-east England rapidly becoming an aerial battlefield. Over Canterbury, the first Polish Spitfire pilot would die, Flying Officer Franciszek Gruszka of 65 Squadron, who would remain buried with his fighter on Wickhambreux Marsh for over thirty years. A few minutes before 1300 hrs, the Hurricanes of 501 Squadron were patrolling over Canterbury, flying in tight vics of three and climbing in a wide spiral. Unfortunately for the Hurricanes, they had been espied by Oberleutnant Gerhard Schöpfel, leading III/JG26 high above.

Ordering his Me 109s to remain at altitude, Schöpfel, realising that a lone Me 109 was more likely to succeed in successfully ambushing the RAF fighters, dropped into position. The twenty-seven-year old ‘experte’ dropped towards the enemy, achieving total surprise: attacking unseen and out of the dazzling sun, within seconds both ‘weavers’, crossing to and fro behind their Squadron, were dispatched. The remaining Hurricanes, however, flew on – oblivious. Unable to believe his luck, Schöpfel then downed the rearmost aircraft which was soon plunging earthwards in flames. Still, however, 501 Squadron continued climbing in tight formation, completely unaware of their comrades’ fate or that death still stalked them.

One of the Hurricanes so far destroyed by Schöpfel was that of the Polish Pilot Officer Franciszek Kozlowski, who baled out seriously wounded, his aircraft crashing at Raynham’s Farm, near Whitstable. Another was flown by Sergeant Donald McKay, who baled out slightly wounded over Sturry, Canterbury, but Pilot Officer John Bland was killed at Calcott Hill, Sturry. Schöpfel, however, was not yet finished: ‘The Englishmen continued on, having noticed nothing. So I pulled in behind the fourth machine and took care of him also, but this time I went in too close.’

Debris from Pilot Officer Kenneth Lee’s stricken Hurricane hit Schöpfel’s Me 109, oil covering his windscreen. More than satisfied with the results of the last two minutes – which was an unprecedented achievement in aerial combat at the time – the Me 109 pilot dived away.

Elsewhere, Tangmere, Ford and Gosport airfields were battered by Stukas, the fighting ebbing and flowing all day all over the 11 Group area.

In total, on this day the Luftwaffe had flown 970 sorties, and lost sixty-nine aircraft destroyed or damaged beyond economic or practical repair; ninety-four German aircrew were killed, forty were captured and twenty-five were wounded. From this point onwards the hard-hit Stukas played no further part in the aerial assault against England. Indeed, the forces committed by Fighter Command were much stronger than the enemy expected: Air Chief Marshal Dowding’s pilots flew 927 sorties, losing thirty-one fighters, ten pilots killed, twenty wounded.

It was 11 August 1940 that saw the highest number of Spitfire and Hurricanes pilots killed throughout the entire Battle of Britain, twenty-five, its place in history perhaps being ‘The Worst Day’; 15 August 1940 had seen both sides fly more sorties than any other day, the Luftwaffe launching raids along a 500-mile front which saw the daylight defeat of Luftflotte 5, becoming ‘The Greatest Day’ to the British but ‘Black Thursday’ to the Germans. The British historian Dr Alfred Price, writing in 1974, decided that 18 August 1940 was ‘The Hardest Day’, given that as 100 German aircraft had been destroyed or damaged, and likewise 136 RAF machines: ‘On no other day during the Battle of Britain would either side suffer a greater number of aircraft put out of action’.

Sunday, 18 August 1940 undoubtedly deserves a place in history, although for the RAF, thanks to the magnificent efforts of Lord Beaverbrook and his Ministry for Aircraft Production, there was never a shortage of aircraft – it was pilots that were in short supply, especially replacements with combat experience. ‘The Hardest Day’, therefore, needs to be appreciated and understood in that context.

Dilip Sarkar MBE, FRHistS, FRAeS

Link to book.

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.

Kenley Revival link.