Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

The Greatest Day: 15 August 1940

Sunday, 15 September 1940 has gone down in history as ‘Battle of Britain Day’, the critical turning point when it became obvious to all that Fighter Command could not be defeated – despite recent arguments to the contrary, for reasons explained in a future blog, 15 September 1940 deserves its place in history – but what is less well-known is that there were other days on which there were many more sorties flown, aircraft and aircrew lost.

As we have seen in the blog Grave Days: 8 & 11 August 1940, there was visceral fighting over the Channel on those days, involving hundreds of aircraft – and on the latter date Fighter Command lost twenty-five pilots killed or missing, the highest number of casualties throughout the entire Battle of Britain. Sunday 18 August 1940 would see the opposing air forces lose more aircraft than on any other day – but undeniably Thursday 15 August 1940 was the greatest day of all – as we will now explore.

The Luftwaffe had planned to launch its much-vaunted Adler Angriff (Attack of the Eagles) on 13 August 1940 – Adler Tag (Eagle Day) – largely targeting RAF airfields. Bad weather and miscommunication, however, hampered the enemy’s efforts, but nonetheless on Adler Tag the Luftwaffe flew 1,485 sorties and lost forty-five aircraft – the Ju 87 Stuka suffering particularly badly. In response, Fighter Command flew 700 sorties in daylight and a further twenty-seven at dusk or after dark, losing thirteen aircraft – seven pilots of which were safe. To the Oberkommando der Luftwaffe, the Luftwaffe High Command, those thirteen RAF fighters became 134 – leading both Generalfeldmarschalls Kesselring and Sperrle, commanding Luftflotte 2 and 3 respectively, to be satisfied with what the day had achieved. The reality, however, was very different: ‘Eagle Day’ had been a complete failure.

The following day, having flown so many sorties on Adler Tag, enemy air activity was somewhat reduced, to less than 500 sorties, partially owing to ongoing unfavorable weather. The early morning saw low cloud, down to 2,000 feet, and drizzle – further vexing Luftwaffe chief Reichsmarschall Göring, eager to deliver his knockout blow against Fighter Command. Ambitious plans were afoot: large-scale raids by Luftflotten 2 and 3, synchronized, for the first and only time, with a major aerial assault on north-east England by Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff’s Norway-based Luftflotte 5 – which so far had played no significant part in the battle. The meteorologists, however, predicted continued unfavorable weather over England, meaning that, as with ‘Eagle Day’, this massive attack would have to be postponed. Given the predicted adverse weather, Göring summonsed the senior commanders of Luflotten 2 and 3 for a post-mortem conference at his opulent country residence, Carinhall, a large hunting estate north-east of Berlin in the Schorfheide forest. Consequently, the air fleet top brass were absent from the Channel coast at what would prove a crucial time.

By mid-morning on 15 August 1940, weather conditions over southern England suddenly changed: blue skies prevailed and high pressure foretold of fine weather. With Luftflotte 2 chiefs Kesselring and Lörzer, and Jagdfliegerführer Theo Osterkamp all away at Carinhall, executive authority had been entrusted to Oberst Paul Deichmann, the II Fliegerkorps Chief-of-Staff. Deichmann was of the opinion that Göring’s reluctance to launch this massive assault was only because of the poor weather – which no longer applied. Surprised by the improving conditions, Deichmann signaled all units, which had already been brought to readiness as planned, despite the weather, that the proposed attacks would now go ahead. The intention was to saturate the British defences on a vast front, from Exeter to Newcastle: target RAF airfields.

Poor intelligence, however, once more led to questionable target selection, given that, as usual, certain of the airfields selected for bombardment were unconnected with Fighter Command. Nonetheless, Deichmann’s order had supercharged the three Luftflotten with heavy activity from Cherbourg to Aalborg. Having sent his signal, Diechmann then hasted to the ‘Holy Mountain’, Luftflotte 2’s underground bunker beneath Cap Blanc Nez, where the operations officer, Oberstleutnant Herbert Rieckhoff, had just received a signal from Berlin cancelling offensive operations owing to bad weather. It was too late: Luftwaffe units were already taking-off, and in view of the actually improved weather, Deichmann refused to recall the formations. The attack was on – and on a scale hitherto unseen in aerial warfare.

Between 1045 and 1110 hrs, RDF detected a formation of ‘30+’ assembling over Cap Gris Nez and moving North across the Channel. This was actually sixty Stukas of Hauptmann Anton Keil’s II/StG1 and Hauptmann Bernd von Brauchitsch’s IV(St)/LG1 (a son of Feldmarschall Walther von Brautchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the German army), escorted by the Me 109s of, amongst other units, II and III/JG26. The dive-bombers targets were the coastal airfields of Hawkinge and Lympne.

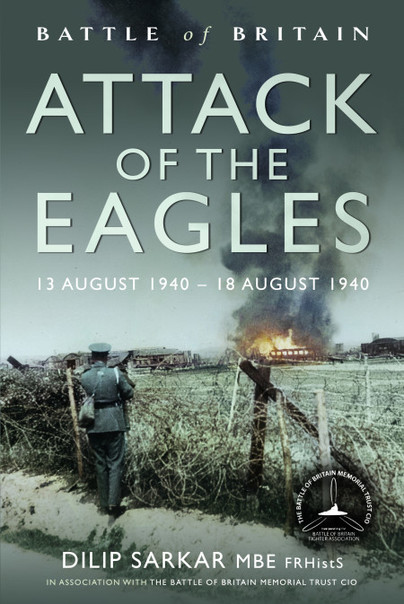

The subsequent aerial fighting is documented minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow, proliferated with first-hand accounts in Attack of The Eagles: 13 August 1940 – 18 August 1940, being Volume 3 of the eight volume, one-million-word, official history I have recently completed for The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust and National Memorial to The Few, published by Pen and Sword.

Suffice it to say here that the attacks on southern England were no surprise – but the first threat to 13 Group, covering the north-east, materialized at 1208 hrs, when RDF forewarned of 20+ bandits over the North Sea, opposite the Firth of Forth. Two more formations were soon indicated, all three flying south-west and heading for the north-east coast above Tynemouth, between Acklington and Blyth. This overall formation was actually much bigger than shown on the radar screen: sixty-three He 111s of Oberstleutnant Hermann Busch’s I and Major Günther Wolfien’s III/KG26, all based at Stavanger/Sola, escorted by twenty-one Me 110s of Hauptmann Werner Restemeyer’s Stavanger-Forus-based I/ZG76, bound for RAF airfields at Dishforth and Linton-on-Ouse.

Owing to the distance from Stavanger to Dishforth being nearly 400 miles, with additional flying time for take-off, assembly, attack and landing, and allowances for any navigational errors, it was impossible for Me 109s to escort the bombers, and even Restemeyer’s Me 110s had to be fitted with auxiliary ‘Dakelbauch’ (Dachshund) fuel tanks to make the trip. In an attempt to confuse the British RDF, Restemeyer’s ‘Dora’ was also fitted with a radio jamming device operated by his back-seater for this trip, none other than Fliegerkorps X’s chief signals officer, Hauptmann Hartwich.

At Drem, Flight Lieutenant Archie McKellar’s ‘B’ Flight of 605 Squadron was ‘available’ when scrambled, hurrying into the air ten minutes later, at 1205 hrs, to patrol Acklington-Tyneside. At 1220 hrs, ten Spitfires of 72 Squadron, led by Flight Lieutenant Ted Graham, were ordered into the air from Acklington to investigate the raid now approaching the Farne Islands. 1242 hrs saw the Hurricanes of Acklington’s 79 Squadron also scrambled to patrol the Farne Islands, followed by the Spitfires of Catterick’s 41 Squadron at 1245 hrs which were ordered to patrol ten miles North of base. If the approaching enemy aircrews expected to meet little or no fighter opposition, based upon Schmid’s assessment, they were about to receive a sharp shock – although arguably the use of radio counter-measures suggests that a strong defence was anticipated.

72 Squadron was first to shout ‘Tally Ho!’, at 1245 hrs, as Flight Lieutenant Ted Graham recalled: ‘I was leading 72 Squadron, and the German formation was quite a sight, something I will never forget, and I must confess to have reported the en enemy in a rather excited manner!’

Pilot Officer Harry Welford was up with 607 Squadron from Usworth and recalled that, upon sighting the enemy, ‘‘I’d never seen anything like it. They were in two groups, one of about seventy, the other about forty, like two swarms of bees. There was no time to wait and so we immediately took up station and delivered No 3 attacks in sections. As only three Hurricanes at a time, flying along nicely in formation, attacked a line of twenty bombers, I didn’t see how their gunners could miss us. We executed our attack, however, and despite the fact that I thought it was me being hit all over the place, it was their machines which started dropping out of the sky. In my excitement, during the next attack I only narrowly missed one of our own machines whilst doing a “split-arse” breakaway – there couldn’t have been more than two feet between us! Eventually, spotting most of the enemy aircraft dropping down with only their undercarriage damaged, I chased a He 111 and filled the poor devil with lead until first one, then the other, engine stopped. I then enjoyed the sadistic satisfaction of watching the bomber crash into the North Sea. With the one I reckoned to have damaged with my first attack, these were my first bloods, and so I was naturally elated.’

The RAF fighters – the presence of which was unexpected owing to typically incorrect Luftwaffe intelligence, harried the Germans without quarter. Once more, it had all gone wrong for the Germans. He 115 seaplanes had first flown a feint towards Montrose, intending to confuse the defences and divert attention from the main attacks, but this only served to alert 13 Group to the main threat. After first intercepted by 72 Squadron, the raiders had actually separated into two formations, one of which crossed the coast North of the Tyne – representing a serious navigational error, given that the intended targets were much further South.

Strangely, the Me 110s made no attempt to cross the coast and some RAF pilots remarked on their impotency, making little effort to counter-attack, leading to a supposition that rear-gunners had been sacrificed to save weight for extra fuel. Under heavy attack, the He 111s largely dropped their bombs in the sea. The southerly force, apparently comprising bombers only, similarly bombed to no effect around Seaham Harbour, the only major damage caused being to civilian properties in Sunderland. Neither formation reached its intended target, and, in any case and yet again, neither Dishforth or Linton-on-Ouse were Fighter Command aerodromes – the irony being that even had they been successfully bombed Britain’s defences would have remained unaffected.

Although RAF combat claims arising were wildly exaggerated, KG26 lost eight He 111s whilst ZG76 lost seven Me 110s – including the Kommandeur of I/ZG76, Hauptmann Restemeyer. The defenders had achieved a remarkable victory, considering that no military objectives were hit and no RAF pilots were lost. Indeed, in the words of Basil Collier in the official history The Defence of the United Kingdom, ‘… 13 Group and the 7th Anti-Aircraft Division, commanded respectively by Air Vice-Marshal RE Saul and Major-General RB Pargiter, could justly claim to have fought one of the most successful air actions of the war’.

The situation was well summarized by Air Chief Marshal Dowding, Fighter Command’s Commandfer-in-Chief: ‘The sustained resistance which they were meeting in south-east England probably led them to believe that fighter squadrons had been withdrawn, wholly or in part, from the North in order to meet the attack… the contrary was soon apparent, and the bombers received such a drubbing that the experiment was not repeated.’

Never again would the Luftwaffe mount such a major attack, from Portland to Newcastle – a front of over 500 miles – and, significantly, no further daylight attack would be made by Luftflotte 5. The Germans flew nearly 2,000 sorties in total, a unique effort, and Fighter Command just under 1,000. Inevitably, combat claims, by both sides, were exaggerated, given the numbers of aircraft engaged and confusion of battle; RAF pilots claimed over 180 German aircraft destroyed, the actual figure being nearer seventy-five.

When the Air Minister questioned Dowding regarding the accuracy of these figures, his response was succinct: ‘If the German claims were correct, they’d be in England by now’. Conversely, the Jagdwaffe claimed 108 RAF fighters destroyed, of which eighty-two were believed to be Spitfires and Hurricanes – the reality was twenty-five of both types were lost, and at least twenty-seven damaged, although most were repairable. Seventeen Spitfire and Hurricane pilots had been killed or were missing, however, although this was less than on 11 August 1940, which saw the most Spitfire and Hurricane pilots lost in a single day (twenty-five), twelve wounded and three captured. In addition, one Blenheim had been damaged in action and crash-landed with two wounded aircrew aboard, and another had been damaged by a ‘friendly fire’ incident, wounding a crewman.

Of Dowding’s victory, Churchill wrote that, ‘The foresight of Air Chief Marshal Dowding … deserves high praise, but even more remarkable have been the restraint and the exact measurement of formidable stress which had reserved a fighter force in the North through all these long weeks of mortal conflict in the South. We must regard the generalship here shown as an example of genius in the art of war’.

On this day of days, Churchill had actually watched events unfold and personally witnessed the high tension and drama from the vantage point of the observation gallery in Air Vice-Marshal Park’s underground Operations Room at 11 Group’s Uxbridge HQ. The Prime Minister was there with his chief staff officer, General Hastings Ismay, and, was deep in thought as the pair were driven back to Chequers, the Prime Minister’s country house in Buckinghamshire.

‘Don’t speak to me’, Churchill told his companion, ‘I’ve never been so moved’ – having actually witnessed what was really the greatest day of the entire Battle of Britain. Churchill then said, spontaneously, ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’ – which, in a few days’ time would be part of a long speech to the House which would launch a legend.

Dilip Sarkar MBE, FRHistS, FRAeS

Link to Volume 3.

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.