Author Guest Post: David Ian Hall

One Hundred Years Ago – The Beer Hall Putsch, 8/9 November 1923

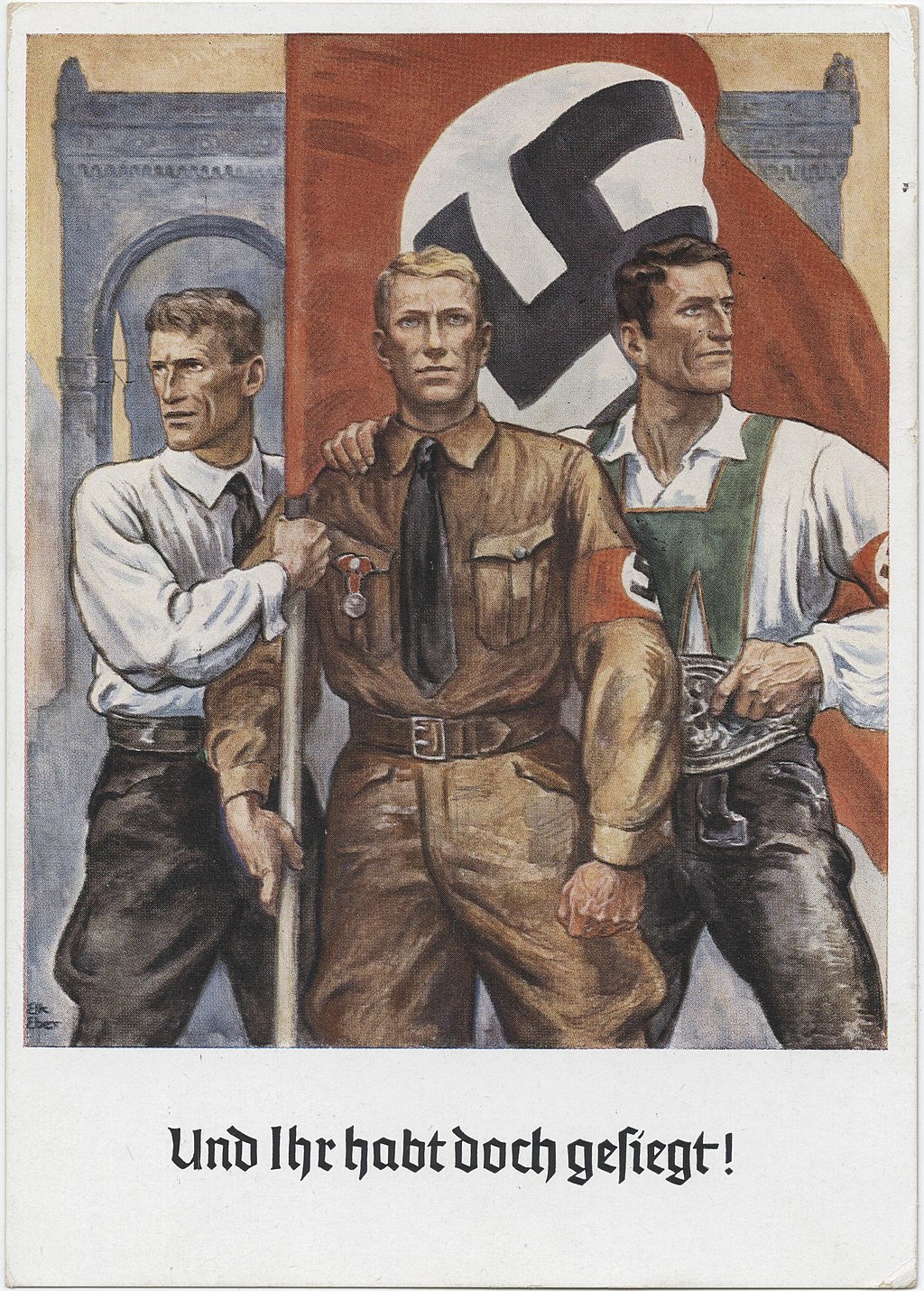

‘Der Neunte Elfte’ – the ninth of the eleventh. This is the name the Nazis gave to their ill-fated 1923 putsch in Munich. Hitler’s attempt to seize power in Bavaria and provoke a national revolution had gone drastically wrong. Sixteen members of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP, National Socialist German Workers’ Party) had been shot dead by the Bavarian State Police, scores more were wounded, and many of the putschists were immediately arrested. Hitler got away but was found and arrested two days later and taken to Landsberg prison. Hitler’s detractors lauded his demise and chortled that National Socialism was dead. Yet a mere two years on from the fiasco in front of Munich’s Feldherrnhalle the Nazis were commemorating the putsch as a formative event in their party’s inexorable rise to power. 8/9 November became the most sacred days in the Movement’s liturgical calendar. Once in power Hitler and the entire hierarchy of the Nazi Party gathered annually in Munich to celebrate the anniversary of the putsch. There were concerts, gala receptions and speeches, parades, and an elaborate re-enactment of the fateful march from the Bürgerbräukeller to the Feldherrnhalle where the martyrs of 1923 were honoured, and SS recruits pledged Treue bis in den Tod (loyalty unto death) to their Führer.

1923: A Bavarian Revolution to Save Germany

A profound sense of betrayal and bitterness prevailed in Germany after the Great War. There was widespread hatred of the ‘November criminals’ – the politicians in Berlin who stabbed the Army in the back and acquiesced in the Versailles Diktat – and fear that the communists sought to impose an alien way of life on the German people. Occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian troops in early 1923 and the catastrophic devaluation of the reichsmark it caused in the autumn led to an upsurge of nationalist outrage in Bavaria. Even the Bavarian government called for a national revolution but preferred that right-wing forces in northern Germany and the Army depose the Weimar government.

Hitler together with General Erich von Ludendorff wanted to march on Berlin and establish a dictatorship, just as the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini had when he marched on Rome the previous year. They thought they had won over Gustav von Kahr, the Bavarian State Commissioner, and other representatives of the Bavarian government at the Bürgerbräukeller on 8 November, but later that night the politicians lost their nerve and ordered the arrest of the putschists. Hitler and Ludendorff tried to regain the momentum. At midday on 9 November, they led a march through the centre of Munich to the Feldherrnhalle where it ended in a hail of gunfire from the Bavarian State Police.

9 November 2023 marked the 100th anniversary of the ‘beer hall’ putsch in Munich. It was the starting point of Hitler’s rise to national prominence which culminated ten years later when he became the Führer of the Third Reich.

Thank you for reading my recent post. For earlier posts on Hitler’s Munich please see Pen & Sword Blog, Hitler’s Munich, January 1921 (12 and 19 January 2021), and 4 November 1921 (Parts I and II).

Author Bio:

Dr Hall is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at King’s College London, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and the author of Hitler’s Munich: The Capital of the Nazi Movement (Pen & Sword Military UK, 2020).

Order your copy here.