Author Guest Post: Celia Lee – Part 2

THE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE HAMILTONS AND THE CHURCHILLS

by Celia Lee author of:

JEAN, LADY HAMILTON (1861-1941)

DIARIES OF A SOLDIER’S WIFE

Part 2

OUT BREAK OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR (1914-18)

A major war would alter the lives of the Hamiltons and Churchills for the future. Britain’s entry into the First World War (1914-18) was a shock to everyone. No one was prepared and that included these two families. Winston and Clementine along with Jack and Lady Gwendeline Churchill (the two women being known in the family as Clemmie and Goonie), were actually on holiday in two cottages next door to each other, at Overstrand, Norfolk, by the sea, when war was declared. It was a terrific shock especially to the wives. Their children had been playing happily in the sand, and the buckets and spades had to be tidied away earlier than expected so that they could return home.

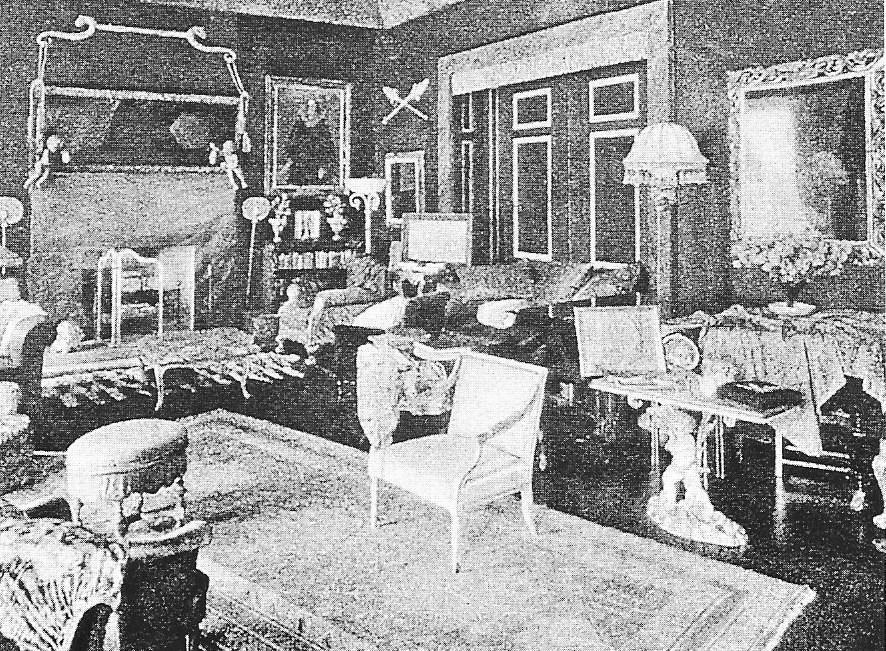

Winston was immediately busy at the Admiralty, Jack left his city job as a stockbroker and went into uniform and thence to France with his regiment. The Hamiltons were at their prestigious mansion home, No.1 Hyde Park Gardens.

There was instantly a meeting of minds between Winston and Hamilton and the Liberal Party Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, that would lead to the fated Dardanelles campaign and the disastrous amphibious landings on the Gallipoli peninsula.

The initial suggestion for an attack elsewhere than on the main theatre of war, the Western Front, was first mooted by Maurice Hankey, a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Marines who, as Secretary to the War Council in 1914, produced the Boxing Day Memorandum, in which he favoured an attack on Turkey, through the Dardanelles as an alternative to the trench stalemate in France and Flanders.

Winston Churchill took up the idea, in response to an appeal from the Russians early in January 1915, as a means of diverting Turkish forces away from their offensive in the Caucasus, and he suggested the attack should take place at Gallipoli.

The actual attack was made by the Royal Navy alone, but the guns in the Turkish forts guarding the Dardanelles, the sea passage between the Gallipoli peninsula and Asia Minor, proved too much for the fleet. The warships were unable to suppress their fire long enough for the minesweepers to clear the minefields in the Dardanelles Straits. As the Navy got into increasing difficulty, it was finally realised that troops would be needed to complete the operation.

The newly-appointed War Secretary, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, approved the release of troops from England and Egypt, and placed General Sir Ian Hamilton in command of the Constantinople Expeditionary Force (later renamed the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force), then gathering in the eastern Mediterranean. Initially, Hamilton’s orders were only to support the navy in its operations. The major naval attack, March 18, 1915, ran into an undetected new minefield and was broken off after heavy loss of ships. At a meeting between Hamilton and the commander of the fleet, Admiral de Robeck, it was decided that the army would attack the Gallipoli peninsula and clear it of Turkish guns and forts before the navy would renew its efforts. Together, they would clear the way for the expeditionary force to reach and capture Constantinople and put Turkey out of the war. However, the Dardanelles campaign – the joint naval and military operation – soon became the Gallipoli campaign, Hamilton’s purely military effort to clear the way before the fleet would renew its attack.

The main theme of Jean’s diaries throughout the Gallipoli campaign is her complete faith in her husband and her total conviction that he could have won there and moved on to take Constantinople, which would have gone some way towards winning the war for Britain. The failure at Gallipoli is a highly controversial subject and there are bodies of military historians with varying opinions and, today, it is still a hotly debated subject. Hamilton and Churchill were, however, ‘in it together’ and they had to stand shoulder-to-shoulder in defence of their actions – a point Jean also made in her diary.

The press abused the campaign, apportioning blame on both Hamilton and Churchill, and Lord Kitchener was viewed as indecisive and not up to the job of Secretary for War. Baying for a sacrifice, some wanted General Sir Ian Hamilton court-martialled. It was not until after his recall and his return to England that Hamilton realised fully the damage done to him and the campaign by the journalists, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett and Keith Murdoch, by what they had published in the newspapers. Considering the enormity of his struggle to win at Gallipoli, and the traumatic effect on both his wife and him, of being recalled, to face humiliation, the suggestion can only be viewed as outrageous.

Winston had to resign as First Lord of the Admiralty. He went back into uniform as lieutenant-colonel of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers, commanding the battalion at Ploegsteert, near Ypres, Belgium. Hamilton was left unemployed, his hitherto unblemished career now hanging in the balance and under scrutiny.

The Churchills were obliged to remove from Admiralty House, leaving them with no place to live. The only abode available was Jack and Lady Gwendeline’s home at Cromwell Road, south west London, and the two families of four adults and five children, plus nannies and servants, were squashed into that small house, being joined later by the now divorced Lady Randolph, who Clemmie and Goonie called Belle mère (beautiful mother-in-law). The women were all living on their nerves in case the two breadwinners Winston and Jack would be killed in the war. Lady Gwendeline went to Blenheim Palace and helped with the hospital there for troops, but she worried so much about Jack that she became a chain-smoker. Winston, ever dramatic, made his Last Will and Testament, though he had little to leave, before setting out to Ploegsteert, Belgium, commonly known amongst the British Tommies as ‘Plug Street’. Jennie wrote to him:

‘Please be sensible, … I think you ought to take the trenches in small doses, after 10 years of more or less sedentary life – but I’m sure you won’t “play the fool” – Remember you are destined for greater things … I am a great believer in your star … .’

In 1916, the Hamiltons had taken Postlip Hall, Winchcombe, in the Cotswolds, Gloucestershire, for a holiday, and Winston was staying with them. Jean wrote of an after-dinner scene:

‘We had a very exciting dinner. Winston after two large goblets of iced champagne, became very communicative. … Afterwards in the drawing-room, he walked about the room, declaiming, shouting, trying his oratory on me, as Ian says. He was terribly excited, talking about Lord Kitchener, said he had a spitting toad inside his head, he pressed his hands hard over his own head and eyes to show the baffled weariness of trying to deal with such a fool.’ (29 May 1916, Postlip Hall).

CLEMENTINE CHURCHILL OFFERS TO GIVE HER BABY TO JEAN, LADY HAMILTON

It was during this difficult time, when Winston and Clementine Churchill were homeless and relatively penniless, that Clementine offered to give away her fourth unborn child, (later named Marigold Frances), to Jean Hamilton, who had left it too late to be able to conceive. The actual date was June 18, 1918 as recorded in Jean’s diary. Clementine had been shouldering a heavy responsibility of her own throughout the war. In June 1915, she had taken up important war work by joining the Munitions Workers’ Auxiliary Committee, formed by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Millions of women flocked to the factories to take up posts vacated by men going into the armed services. To maximise production, canteens had to be provided and kept open 24 hours a day to feed the workforce. Clementine became responsible for opening, staffing, and running nine canteens in the north and north-eastern metropolitan area of London, each one providing meals for up to 500 workers.

It was gruelling work, travelling about on a crowded bus from one venue to another, travelling across London as there was no petrol for the car. There were arguments and disagreements to deal with as men complained that women were taking their jobs. The women complained they were being paid a lower rate than the men for the same job. Then Clementine discovered she was pregnant with a fourth child! Following a dinner party at the home of Lord Haldane, (formerly Secretary of State for War, 1905–12), Jean wrote in her diary of the demands still met by Clementine:

‘Clemmie Churchill and Frances [Horner] departed in high dudgeon about 11 o’clock to the night shift of the Hackney Canteen.’ (14 June 1918).

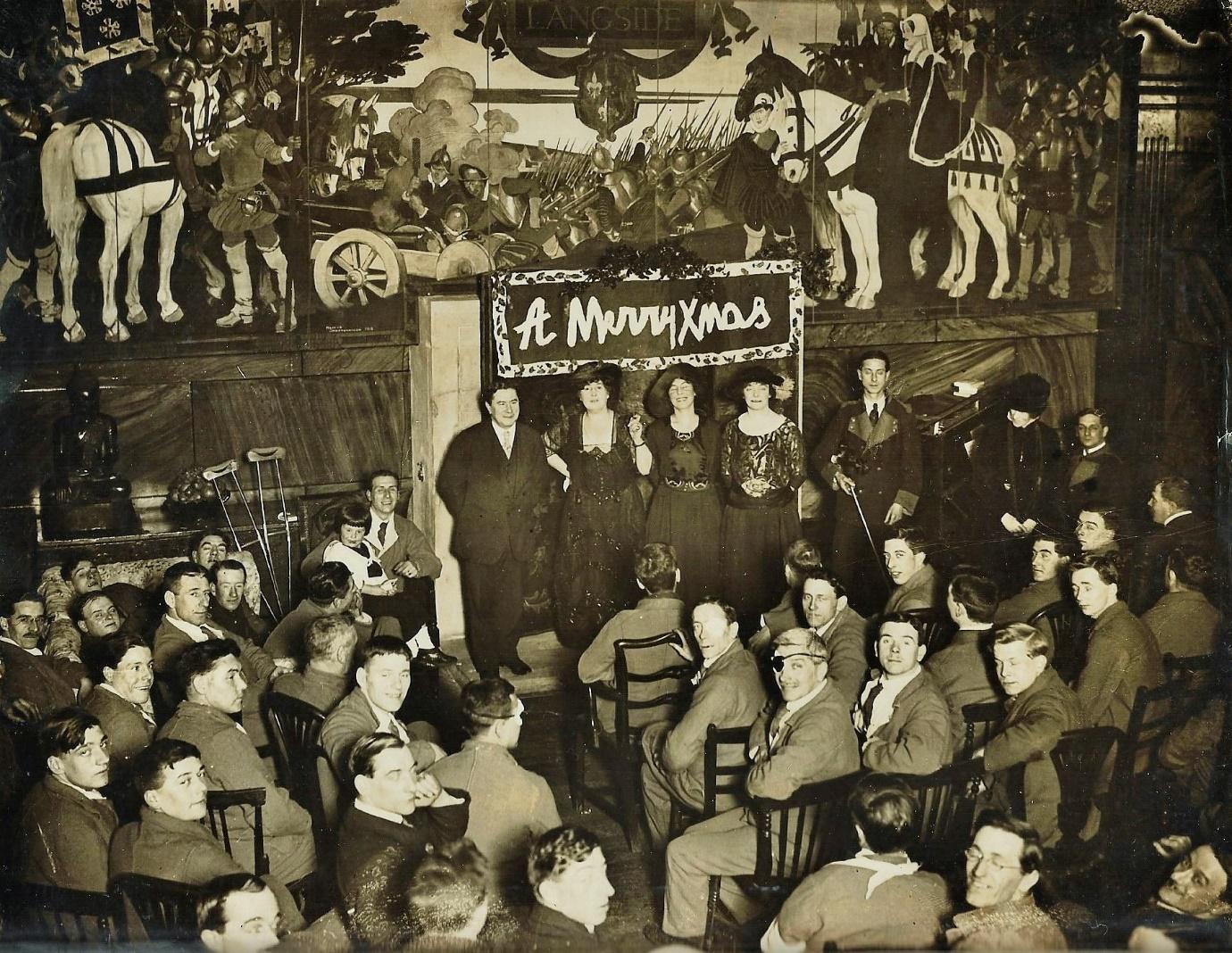

JEAN HAMILTON’S WAR WORK

Jean Hamilton had also taken on a lot of war work, being an active member of the Red Cross. She did not waste a moment, setting about organising food, clothing, and other parcels at her home, to be shipped to the troops. Ian would later write that on certain days throughout the year, their house would be ‘thrown open and a good tea given to meetings of every sort of good work.’ These included injured soldiers invalided out of the war. Jean also set up a Gallipoli Fund to raise cash to buy supplies that were sent to the troops at the Dardanelles. The appeal was published in the newspapers, July 12, 1915, and ‘brought an immediate and most gratifying response.’ Jean was also a member of Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund that was run by a committee on which sat Mr Henry Fenwick Reeve, who was a senior executive officer, and Mrs Charlotte Sclater Honorary Secretary. Hundreds of bales of comforts and medical supplies were packed at Jean’s house, under her supervision, and at the depots of Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund. The supplies were then shipped to the troops at Gallipoli and the base hospitals at Mudros (on the island of Lemnos), Alexandria, and Malta. Jean wrote in her diary on her birthday:

‘No rest or peace all day, telephoning and worry from dawn to midnight. … Heather [her sister] and I were so busy with Red Cross work. … much agitated all day getting ten huge bales of Red Cross things off to Alexandria – they had to be off at 2.30 – Miss Batt, my new war secretary, quite lost her head, but Heather’s chauffeur came to the rescue and took them off in her motor and they were in time.’ (8 June 1915).

During the war, items sent to the troops via Queen Alexandra’s Field Force Fund of which Jean’s efforts was part, included: 17,000 shirts; over 7,500 vests; socks, mufflers, shorts and sweaters; 14,000 mosquito nets; 37,000 towels and 20,000 cakes of soap; nearly 1½ million cigarettes; 1,648lbs. of tobacco and over 13,000 pipes; 1,500lbs. sweets; 359 barrels of apples; boracic and carbolic ointments and Vaseline; 360 mouth organs, 20 gramophones with records, 6 sets of boxing gloves; pocket mirrors, scissors, and soldiers’ ‘housewives’ [sewing kits]. Supplies for the hospitals included 100 pillows and pillowcases, bandages and dressings, slippers and bed jackets. At Mudros, a recreation tent had been erected, capable of holding 500 men, and was equipped with a piano, gramophones, and several refrigerators. [Figures from the Imperial War Museum: BO2/12 Women’s Work Committee, First Report 12 July–30 September 1915, and 12/3, 12/4, 12/5-11, 12/3].

In the midst of it all, Jean could recall happier times, dancing at a ball with Winston Churchill’s secretary, Eddy Marsh, at San Antonio Palace, on the beautiful, sun-soaked, island of Malta, that must now have seemed so far away and very long ago.

THE DARDANELLES COMMISSION OF INQUIRY

Due to the failure of the Dardanelles Campaign, Hamilton and Churchill had to face an official Dardanelles Commission of Inquiry, that was set up in 1916, by Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, the final report of which was withheld, meaning it hung over their heads for many months, until after the war was over. Hamilton and Churchill stuck together to defend their reputations and those of the men who served under them. On June 6, 1916, Hamilton lunched with Winston at Cromwell Road, where Churchill was still living at the home of Jack and Lady Gwendeline. The house stands to the present day, directly facing the Natural History Museum. The meeting was to enable them to go through something in the region of twenty cables that had been sent from Gallipoli to Kitchener, appealing for men and munitions in support of the active operations there. The cables had been held by Kitchener and never replied to or shown to the Cabinet, constituting negligence on his part. Hamilton and Churchill were planning to use these to expose Kitchener, and in support of themselves and their actions, in relation to the Dardanelles campaign. Whilst they were thus engaged a news boy visible from the window, ran along the pavement shouting: ‘Kitchener drowned! No survivors!’ Earl Kitchener had drowned, June 5, whilst on his way to Russia on HMS Hampshire to attend negotiations with Tsar Nicholas II. The ship struck a German mine 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Orkney and sank with the loss of over 700 lives. Kitchener’s body was never recovered.

Hamilton described their reaction to the news: ‘We looked at one another with wild surmise like Cortes at the Pacific from the heights of Darien. … Had I put the idea of going to Russia into his head?’ There had been talk of Hamilton going to ‘Russia to give the Czar his field-marshal’s baton … .’ It had been decided that Kitchener should go instead. ‘When we came into the dining-room, Winston signed to everyone to be seated and then, before taking his own seat, very solemnly quoted: “Fortunate was he in the moment of his death!” It was now impossible for Hamilton and Churchill to implicate Kitchener in the way that they should, and his failure to support the campaign went unsaid.

The delay in publishing the Report on the Dardanelles Commission of Inquiry would seem to have been deliberate, probably to save the reputations of the War Cabinet and absolve them of any blame. Hamilton was never again employed in active service and, somewhat ironically, was offered and accepted the post of Constable of the Tower of London, that he held until his retirement. Winston Churchill who was then in his early-40s had to entirely rebuild his career and his credibility as a politician, which he did to an incredible degree – but he never forgot what he owed to Hamilton.

During the Second World War, (1939-45), Hamilton was writing his memoirs Listening for the Drums. In a chapter about Winston he said:

“… no-body, not even Lord Bobs in all his glory, has touched my life at so many points as Winston Churchill. So much indeed has he done so that were my pages to give no glimpses of his strange voyage through the years, showing him sometimes as the Flying Dutchman, scudding along under bare poles; sometimes as the Ancient Mariner under flapping canvas in a flat calm; sometimes as a small boy playing with goldfish; my story would not be complete. As a sample – on the 6th January ’41 Bardia had fallen; – red-hot news. Before it began to cool it must be hammered into all sorts of shapes and handed out through many channels leading to Finance, Parliament, and the World. Every second was priceless yet he paused to let his mind fly back to forty-one years to end a special message to an old comrade of the wars who had long since ceased to interest the Press, Parliament of Finance.” [Quoted: Hamilton, General Sir Ian, Listening for the Drums, pub. Faber & Faber 1944, p.238.]

Lord Bobs was the Hamiltons’ nick-name for Frederick, Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in India. Hamilton’s reference to ‘Bardia’ was to the British capture of Bardia in Libya from the Italians. Hamilton then went on to quote a telegram he had received from Winston, January 6, 1941:

Post Office Telegram London 12.43, addressed to General Sir Ian Hamilton, Blair Drummond, Perthshire.

“I am thinking of you and Wagon Hill when another January 6th brings news of a fine feat of arms. Winston.”

It was to Winston’s credit as British wartime Prime Minister, that he remembered his mentor of an earlier time. The relevance of the date, January 6 was that it was on that date in 1900, during the South African Boer War, that Hamilton defeated the Boers at Wagon Hill in the siege of Ladysmith. Ten days after receipt of the telegram, January 16, was Hamilton’s 88th birthday. Jean and Ian were staying at her brother Sir Alexander Kay Muir’s home, Blair Drummond Castle, partly to escape the bombing in London, but much more-so because Jean was dying of cancer. Churchill’s thoughtfulness must have come as a comfort to Hamilton at such a time. Jean held on throughout February 22, their fifty-fourth wedding anniversary, and slipped away the following day.

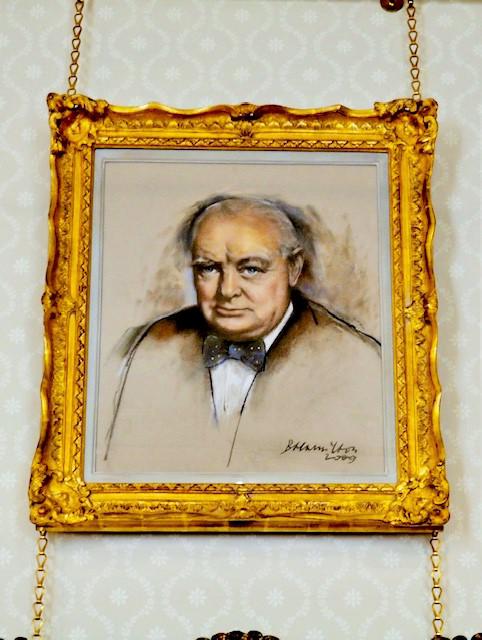

The friendship between the Hamiltons and the Churchills has continued to the present day. Mrs Barbara Kaczmarowska Hamilton painted a portrait of Sir Winston Churchill that enjoys pride of place, hung in the room at Blenheim Palace where he was born.

Blenheim Palace. By kind permission of Mrs B. Hamilton.

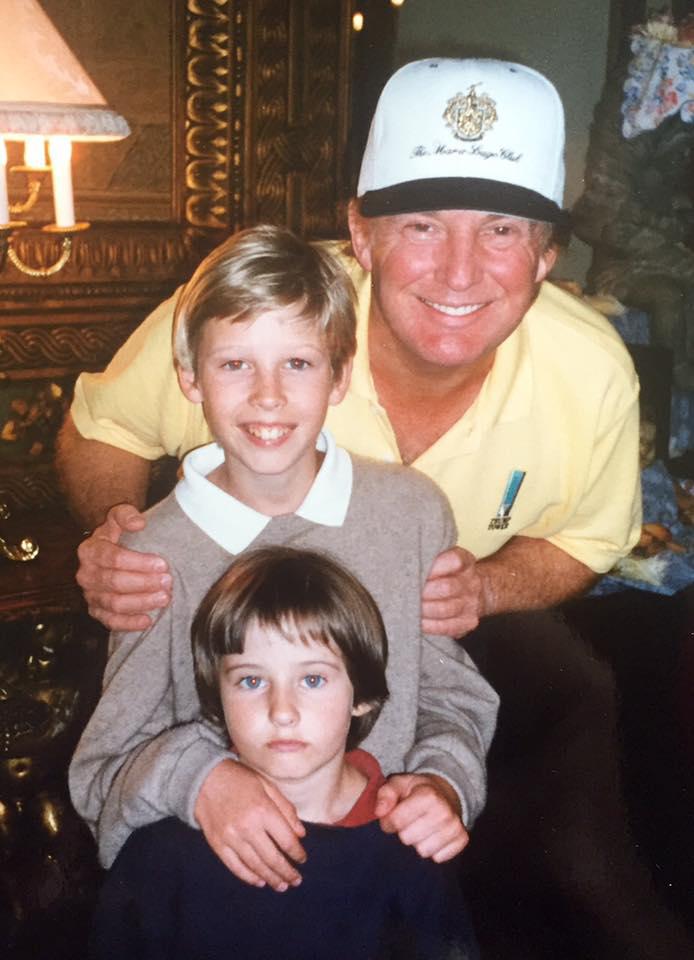

President Donald Trump who plays golf with Felix and Maximilian Hamilton, the sons of Ian and Barbara, upon becoming president, reinstated Jacob Epstein’s bust of Sir Winston Churchill in the White House’s Oval Office.

Click on the below weblink to hear Celia Lee, British delegate, speaking on Winston & Jack the Churchill Brothers, at a Churchill Society Conference, Franklin, Tennessee, March 2018.

Sources:

Celia Lee, Jean, Lady Hamilton (1861-1941) Diaries of A Soldiers Wife, pub. 2020, Pen & Sword, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK, and 1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA. Electronic editions available now. Hard cover pub. October 2020, available in bookshops and over the internet, including Amazon:

Hard cover ISBN 9781526786585; October 2020.

ISBN E-Pub: 978152678594; Available now.

ISBN Kindle: 9781526786609;

ISBN PDF: 9781526786616.

John Lee, A Soldier’s Life: General Sir Ian Hamilton 1853-1947, pub. 2021, Pen & Sword, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK, and Havertown, PA 19083, USA.

Celia Lee and John Lee, The Churchills A Family Portrait; pub. February 2010, Palgrave Macmillan, New York and London, hard cover and soft cover, available in book shops and the internet, along with electronic editions.

General Sir Ian Hamilton, Listening For the Drums; pub. Faber & Faber, 1944, p.238.

…………………………………………………