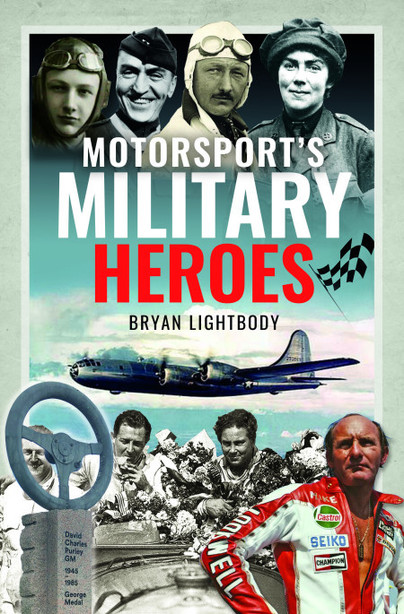

Author Guest Post: Bryan Lightbody

It is the first part of June, and it may be a few days late, but it seems appropriate to commemorate the life of racing driver and D-Day veteran Ken Miles. One of the protagonists of the movie ‘Le Mans ‘66’ or also titled ‘Ford Vs Ferrari’, the story of how in partnership with Carroll Shelby and the Ford Motor Company, Ford dominated the Le Mans 24 Hour race during the second half of the 1960s. With my interest and enthusiasm for historic motorsport and military history, Shelby and Miles were the inspiration to create the book ‘Motorsport’s Military Heroes’ along with Murray Walker, Raymond Baxter and the subject of my next blog Captain Robert Benoist of the British Special Operations Executive.

Kenneth Henry Miles was born on 1st November 1918 in Sutton Coldfield just outside of Birmingham, England to parents Eric and Clarice. It could probably be surmised that Ken was a maverick from the very start, a case of nature over nurture. At the age of eleven he had his first foray into and taste of the perils of internal combustion engine machines when he rode a 350cc trials motorcycle and crashed it in the dark. He struck a lamp post due to an unfinished piece of road repairs which resulted in the first of many broken noses. He also had a failed run away from home attempt to make it to the United States, but by the age of fifteen he settled into an apprenticeship at Wolseley Motors having left school. He met a girl called Mollie at this time who he vowed at that he would one day marry.

When World War Two broke out, Ken was on the cusp of finishing the apprenticeship at Wolseley Motors and in September 1939, and within eight weeks of the end of that apprenticeship he found himself in a Territorial Army camp and posted to an anti-aircraft unit in an armament producing area. That might well have satisfied an interest in guns. It was an exciting posting for a year before he was moved to a driver training regiment in Blackpool, where he taught disinterested soldiers how to drive army vehicles. Ken recounted that the worst candidates were former London taxi drivers who were convinced that nobody could teach them anything. During his time in Blackpool his nose was broken again in a brawl.

Mollie and Ken married in 1942 and he was sent to join the Royal Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) and promoted to staff sergeant. To complete this move Ken had to undergo a technical training course in the south of England and emerged with the highest marks. He was then posted to a tank unit on the east coast of England. Meantime Wolseley had turned all of their manufacturing capacity over military production. Between 1942 and 1944 Ken was moved around the UK several times, breaking his nose twice more, before landing in Normandy, according to Mollie’s recollection, on D-Day ‘plus two’ (meaning two days after the initial landings took place, D+2). Ken demonstrated his continued interest in vehicle technology and knowledge having a letter published in ‘Motorsport Magazine’ in August 1943. He commented on his intention to fit a supercharged engine in a car as a competition project after the war.

The first REME elements ashore on D-Day were the armoured recovery vehicles of the beach recovery sections which landed immediately after the assault to be closely followed by crawler tractors and wheeled recovery vehicles. These beach recovery vehicles worked extremely hard under most adverse conditions as in places they were under shell fire and at night recovery work was made even more difficult by the presence of mines and explosive charges secured to under-water obstacles, to say nothing of the nightly visits from enemy aircraft. This would have been much of Ken’s experience. ‘Drowned’ vehicle parks were established near the beaches for the repair of drowned tanks, guns and vehicles.

Armoured brigade workshops were given first priority of the phasing in of resources, followed by corps troops workshops scaled for gun repair work. By D+3 seventy-five per cent of these workshops had landed and on the afternoon of D+1 three complete workshops were already functioning. For Ken on D+2 he would have been heavily involved in much of those logistics. Records on his landing day are mixed, it is shown he might have landed on any of D+1, D+2 or D+3.

Between D+2 and D+11 669 vehicles were brought into the workshops, 509 were repaired and returned to units and 130 classified as beyond local repair, the remainder being written off. Ken must have been up to elbows in grease, oil and sand.

Ken moved on from Normandy and saw service in France, Holland, Belgium and Germany. His specialism was tank reconnaissance and recovery, the latter being a gruelling and often a horrific job with mind to the Germans naming the mainstay Sherman tanks as ‘Ronsons’, in reference to how easily they ‘lit up’ (caught fire). It can only be imagined that many vehicles he recovered still had the wounded or dead occupants inside, or sadly parts of them. Ken’s unit was the first to pass though the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, undoubtedly witnessing the worst of the horrors there. After the German surrender, he was stationed close to the Baltic Coast where, until he was demobilised in January 1946, he spent time organising motorcycle races and sailing yachts.

When he returned home, he returned to Wolseley and to Mollie, with whom he moved into a new house in Molseley, Birmingham in 1947. As she says, ‘he bought a Frazer-Nash car to race when I wasn’t looking’. Good to his intention in his letter to ‘Motorsport’ he fitted a supercharged Mercury V8 engine to this car and in his first race at Silverstone in April 1949 he placed second.

In 1951 Ken’s connection to a childhood friend John Beazley came back into play. Beazley had become the general manager of Gough Industries in southern California who were the local MG cars distributor. Beazley was looking for a knowledgeable and capable manager for the service department, and Ken was his natural and first choice. Ken moved there in December 1951 with Mollie and their son Peter joining him very soon after. By April 1952 Ken drove in his first race in a Gough Industries MG-TD and his driving ability soon became apparent. In 1953, he won 14 straight victories in the Sports Car Club America racing series in an MG-based special of his own design and construction. But also his maverick and wayward nature began to be part of his reputation too, culminating in him being fired in May 1955 from Gough as a result of a disagreement with the company controller Phil Gough.

Miles’ story as the ‘Stirling Moss of the West Coast’ is legendary, winning 38 of the first 44 races he entered. He opened his own garage and became friend and partner of Carroll Shelby, being heavily involved in developing the Ford GT40 in 1960s, effectively winning Le Mans in 1966. His incredible racing career as one of the greatest drivers many have never heard tragically ended in August 1966 whilst testing the next generation GT40, and is recounted in his chapter of ‘Motorsport’s Military Heroes’.

Read more in Motorsport’s Military Heroes.