Author Guest Post – Andrea Hetherington

Desertion in the First World War – a new perspective

The subject of Britain’s First World War deserters is one you may think you know already. The story of the men shot at dawn by the British Army for the crime of desertion and pardoned almost a century later has been told frequently in recent years.

Would it surprise you to read that the men who were shot at dawn were just a tiny proportion of men who deserted? And that the majority deserted within Great Britain, and often faced inconsequential punishments, many avoiding court martials even if they were apprehended?

This book arose out of a phenomenon I came across when writing my previous work, Britain’s First World War Widows – the Forgotten Legion. I discovered several rogues who romanced war widows and even married them in order to get their hands on the woman’s pension, promptly disappearing once the money was spent. These men were almost invariably deserters and I started to wonder just how many of these men existed, and how they managed to survive whilst on the run. What I discovered was that desertion was far more widespread than may be imagined.

Only 266 men were shot for desertion during the First World War. 146,733 men during the same time period were declared to be deserters. There were more than 82,000 courts martial held in Britain alone for the offences of absence without leave and desertion.

Those figures may be surprisingly high, but the true rate of desertion is even greater because the court martial statistics only cover men who were put before a tribunal on their rearrest. What the statistics do not reflect is the large number of soldiers who made off and were recaptured yet never appeared before a military court. A court martial could be avoided where a confession was forthcoming and the merits of the case could be met by light punishments including being docked some pay and confined to barracks for a few days. Those who were merely punished by their commanding officer in this way are therefore hidden from the official figures. At the other end of the spectrum, fourteen deserters who were arrested on the home front were returned to their frontline regiments and shot at dawn.

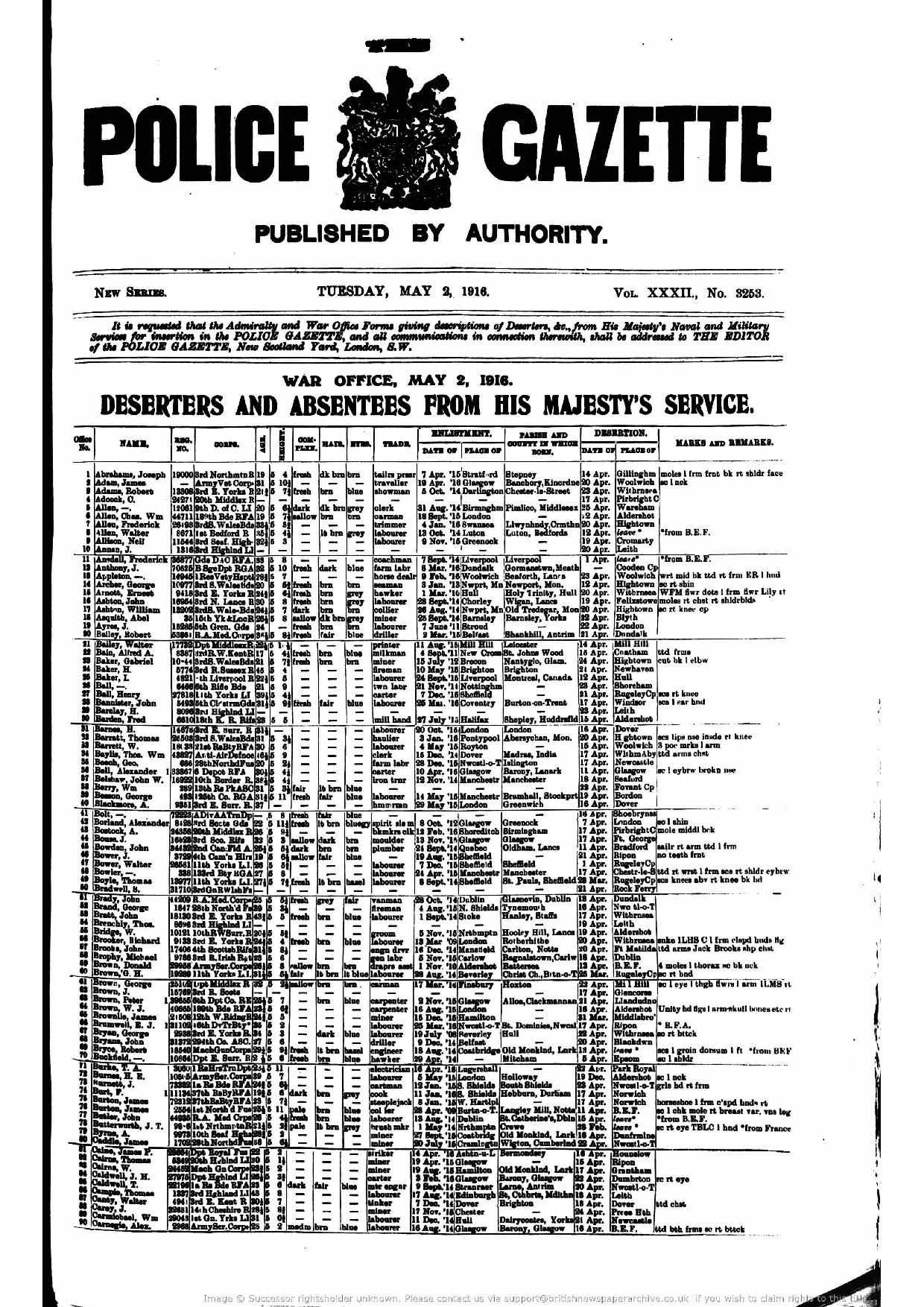

Once a man was deemed by the military to be a deserter his details were passed to the Police Gazette for publication so that police officers could look out for him on his home patch. During the war the Police Gazette carried an average of 1,000 names a week of men who were wanted for absence and desertion. These numbers were supplemented after the introduction of conscription in 1916 with names of men who had failed to answer their call up papers.

Some men joined up with the specific intent of immediately deserting and taking the King’s Shilling with them. Miscreants sometimes worked as a gang, enlisting and deserting en masse. In Belfast in February 1915, four deserters with ten different aliases between them appeared together at court for this very offence. The gang had enlisted in the Royal Irish Rifles the day after enlisting and deserting from the Leinster Regiment. Back in England one determined absconder reportedly managed to join and desert three different regiments between August and October 1914.

Most deserters were not serial enlisters but left the army, either temporarily or permanently, because military life did not suit them at the time. Common reasons for desertion include dissatisfaction with the training camps, family problems, illness, immaturity, and addiction to alcohol. Cowardice was not an accusation that could be fairly levelled at many deserters – amongst the ranks of absconders were men who had served abroad with distinction, some receiving the highest battle honours including the Victoria Cross.

When a man deserted, his army pay was stopped, meaning that he had to find a new source of income. Some turned to offending to pay their way. Alongside burglars and petty thieves were many audacious fraudsters who flaunted their military connections rather than concealed them. Collecting for non-existent charities whilst wearing khaki was a reliable source of cash. Pretending to be a wounded soldier was even more lucrative, the pretence often quickly abandoned on a challenge by a police officer when limping beggars could suddenly run like the wind. Lots of frauds were committed in officer’s uniform, taking advantage of the class bias that valued an officer’s word above that of the average Tommy.

Many deserters sought sanctuary with their families. Coal cellars, outhouses and attics nationwide served new functions as boltholes when the police knocked on the door. Harbouring deserters was a criminal offence and families welcoming their errant men home risked imprisonment. There were other harsh consequences for the family of a deserter as when a man’s pay was stopped so was any separation allowance to his wife and children – a deliberate move to force him to return by starving his family into submission.

Some men deserted in order to provide for their families by taking on jobs that were more lucrative than soldiering. Munitions work was popular with deserters where good money could be earned and one’s conscience could be salved with the thought that a contribution to the war effort was still being made.

Taking some extra time off from military obligations was not seen as a heinous crime by the general public or the average Tommy. There were many slang terms for unauthorized absence, often described as ‘taking French leave’ and no less a patriotic publication than John Bull criticized the arrest of soldiers who had overstayed their leave and campaigned for pardons for deserters. Desertion was part of the everyday experience of many soldiers.

This book sheds new light on the topic of desertion on the home front, which, though the term has become much overused, is certainly one of the ‘hidden’ stories of the First World War.

Andrea Hetherington

Deserters of the First World War is available to order here.