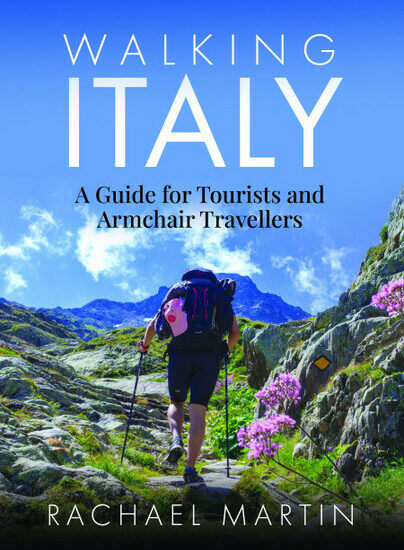

Author Guest Post: Adrian Mackinder

Why the Victorian Era was the Golden Age of the Ghost Story

I’ve always found Halloween a fascinating time of year. Less widely celebrated than Christmas Day, but more so than Easter Sunday – or rather, there are perhaps a greater number of readily conducted rituals surrounding Halloween than Easter. In these more secular times, the religious meaning of Halloween – either Christian or pagan – has been replaced by a general celebration of all things supernatural. The legacy of Allhallowtide, born from Samhain, has ensured that every 31 October, things continue to go bump in the night.

The Victorian period is the Golden Age of the Ghost Story. A time when the spoken word that materialised into the written page was more widely available and affordable than ever, thanks to the steam-powered printing press of the Industrial Revolution. With increasing literacy and the proliferation of public libraries, literature soared in popularity – none more so than tales of the dead haunting the living. The rise in spiritualism also reflects the era’s appetite for the supernatural and there was, for the first time, an abundance of printed tales designed to terrify and astonish.

Our fascination with the supernatural has not abated, but the spectre of Victoriana looms large over the ghost story. The tropes, fashions, interiors and architecture conjure up imagery of hauntings and apparitions arguably more vividly than any other period. Men in starched collars and frock coats sporting outlandish facial topiary, tentatively exploring old dark houses by lamplight. Apparitions of bonneted and veiled chalk-faced women with hollow eyes, sunken cheeks and flowing, bustled funereal dress drifting through ornate garden cemeteries by the light of the full moon. Such tales are steeped in Victorian iconography, so here are my five all-time favourite Victorian ghost tales. Don’t worry. No spoilers. I’ll leave that for you to discover. If you dare!

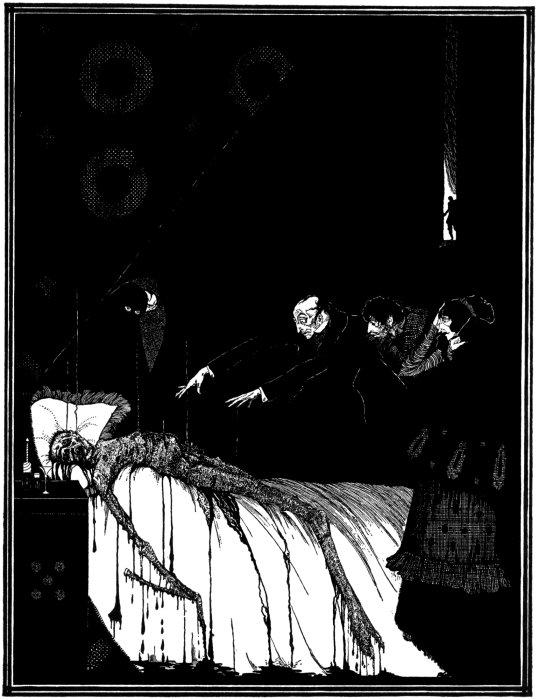

The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar, Edgar Allen Poe (1845)

This is a chilling account of an unnamed narrator who has become fascinated by the occult practice of mesmerism and muses about what would happen if an individual fell into a hypnotic trance right at the point of death. Determined to push the boundaries of popular pseudoscience, the narrator coaxes a good friend, Ernest Valdemar, who is dying of ‘phthisis’ – better known as tuberculosis – into being his test subject. As Valdemar approaches the final year of his life, the narrator performs his craft and keeps Valdemar in a trance state for seven months, until doctors participating in the great experiment confirm that Valdemar has indeed passed on. It is only after this point, however, that things take a sinister and decidedly gruesome turn. Poe was never one to shy away from graphic descriptions of the body in various states of health, but this one, especially at the story’s shocking climax, is very gory indeed.

The Old Nurse’s Story, Elizabeth Gaskell (1852)

With novels and short stories brimming with political and social commentary, Gaskell is not so well-known for dabbling in the supernatural. But in 1852, Gaskell embarked on a wonderful journey into the ghostly realm. She really leans into classic Gothic tropes, but there is still plenty of social commentary within the few pages Gaskell used to tell her tale, namely the plight of the female working classes, helpless against the violent whims of brutish and ignorant upper-class men. This is a delightfully chilling story of the living being haunted by the past, with terrifying phantoms as powerful harbingers of skewed morality. It takes less than an hour to read, but its powerful payoff makes it a hugely satisfying experience.

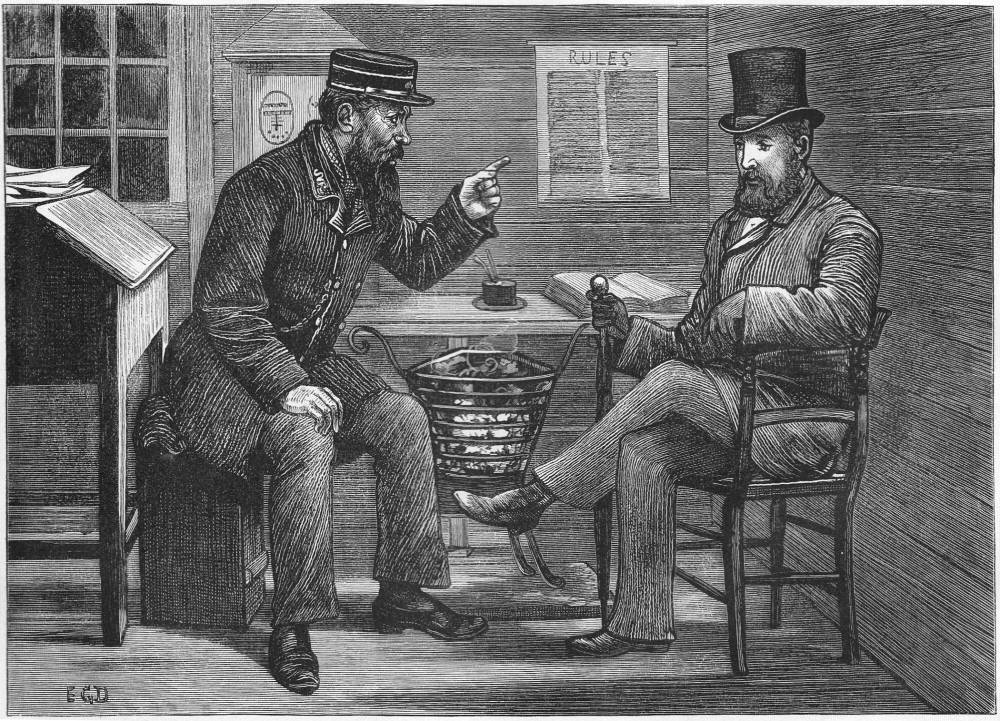

The Signalman, Charles Dickens (1866)

While nowhere near as celebrated as A Christmas Carol, this short story involves a solitary train signalman who is tormented by the ringing of a bell that only he can hear. He is then visited on several occasions by a spirit appearing at the entrance to the tunnel. Each ghostly manifestation heralds a terrible event on the railway line, first a train crash with multiple casualties, then the untimely death of a young woman passing through. The narrator dismisses the signalman’s apparition as hallucination until tragedy strikes a third time, which no one sees coming. Dickens plays with ideas of reality and perception and is deliberately ambiguous in his dramatic conclusion. Was the signalman seeing a ghost, or was it indeed, as the narrator observes, a series of hallucinations? The answer is up to the reader, and that is the story’s power.

Lost Hearts, M.R. James (1895)

Set in 1811, it is the tale of a young orphan boy, Stephen Elliot, sent to live with eccentric older cousin Mr Abney in an isolated Lincolnshire country house. There he becomes plagued by nightmares, wakes to find his night clothes ripped and torn by some unseen force and then becomes haunted by visions of two ghostly children on the grounds, both of whom, disturbingly, have their hearts missing. Lost Hearts is bleak, tragic and unsettling – as all good ghost stories should be. Its ability to shock endures, and M.R. James’ powerful description of what Stephen discovers in the bathtub and the two tiny phantoms on the lawn, as in the best ghost stories, linger in the mind long after.

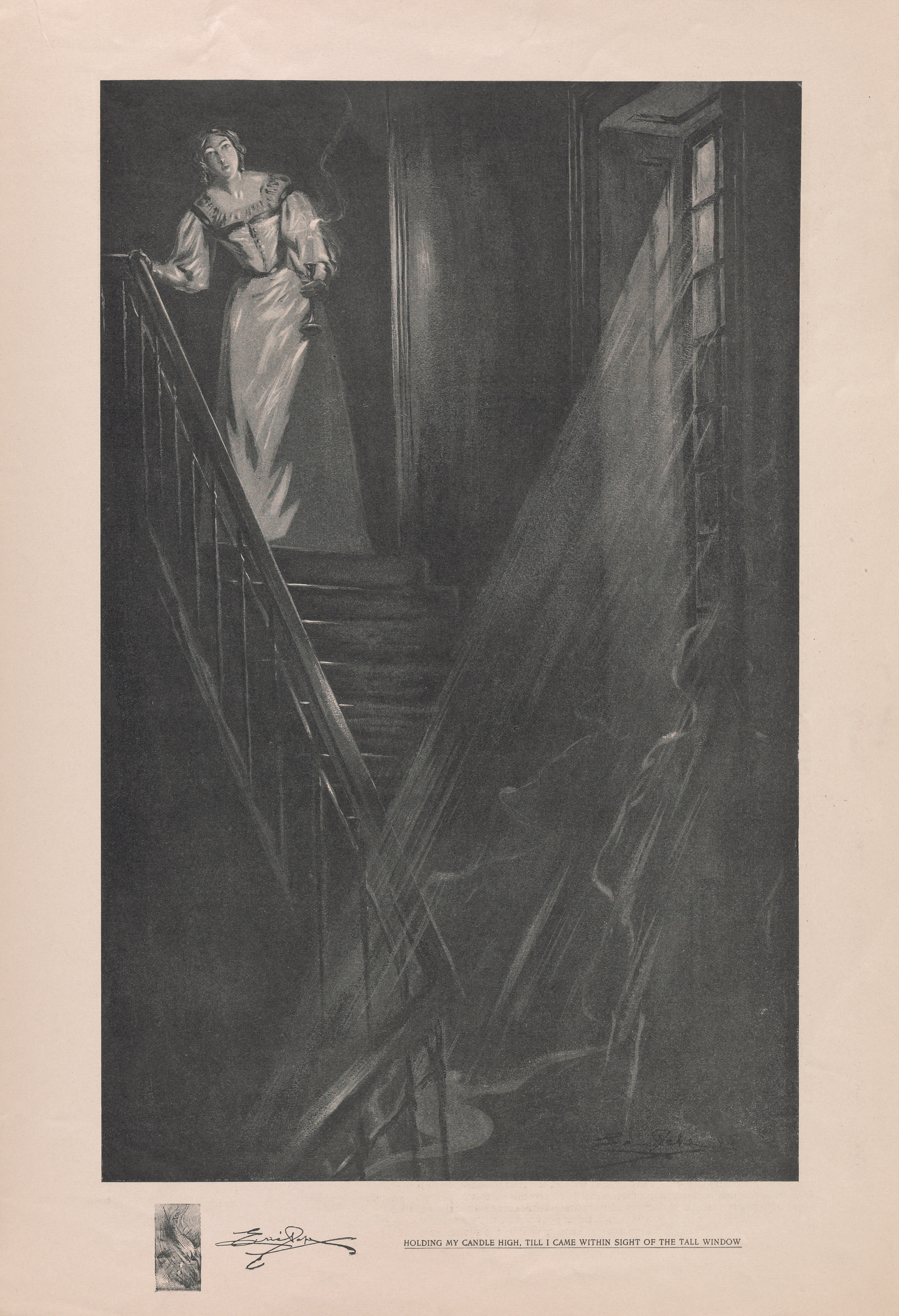

The Turn of the Screw, Henry James (1898)

Like Gaskell’s short story, our final stop on this journey finds us at another remote country pile. The novella begins when a man named Douglas reads a manuscript written by his sister’s late governess, tasked with caring for recently orphaned siblings, Flora and Miles, at Bly Manor in Essex. When Miles’ behaviour turns for the worst and he is expelled from school, the governess soon becomes caught up in unravelling the mystery of Bly Manor, with tragic consequences. The Turn of the Screw is a triumph. Modern horror author Stephen King once wrote that along with Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House, The Turn of the Screw is one of the only two great supernatural works of horror in a century because both feature ‘secrets best left untold and things left best unsaid’.

This is just a tantalising taste of the best ghost tales Victorian literature has to offer. The end of the nineteenth century saw the mysterious, fantastical and melodramatic infused with the modern concerns and moral panics of the Victorian era, as well as its preoccupations with the rapid advance of modernity, science, medicine and technology. The ghost in the machine, it seems, also haunted the minds of the greatest literary figures of the age.

Order your copy here.