Author Guest Post: Aaron Stephen Hamilton

A Re-evaluation of U-853’s Final War Patrol within the Evolving U-Boat Operations and Tactics of ‘Total Undersea War’

By Aaron Stephen Hamilton

The published historical record of the Battle of Atlantic during the Second World War, and more specifically, the development and employment of German U-Boats, is weighted disproportionately on the period of mid-Atlantic convoy battles through mid-1943. The absence of a broader historiographic survey that includes a detailed accounting of evolving U-boat technology and tactics during the final year of war has eluded serious study for over seventy-five years. More importantly, it has distorted the interpretation of some U-boat combat actions during the final year of the war, as well as the maritime archeology of U-boat’s sunk in this period, particularly along the US East Coast. The new study Total Undersea War: The Evolutionary Role of the Snorkel in Dönitz’s U-Boat Fleet 1944-1945 provides the first comprehensive look into this period of the Battle of the Atlantic.

The work focuses on how the U-boat not only survived as a weapon system after the defeat of Wolfpack tactics during the ‘Black May’ 1943, but how its operations and tactics evolved after the introduction of an air mast, known in German as the Schnorchel (snorkel), into what became known within the U-boat force as ‘Total Undersea War’. Using this data, much of which is published for the first time, we will examine how it offers a different perspective on the final wartime cruise of U-853 sunk off Block Island on May 6th, 1945 and how the U-boat remained a potent, though diminished, threat through the last day of the war.

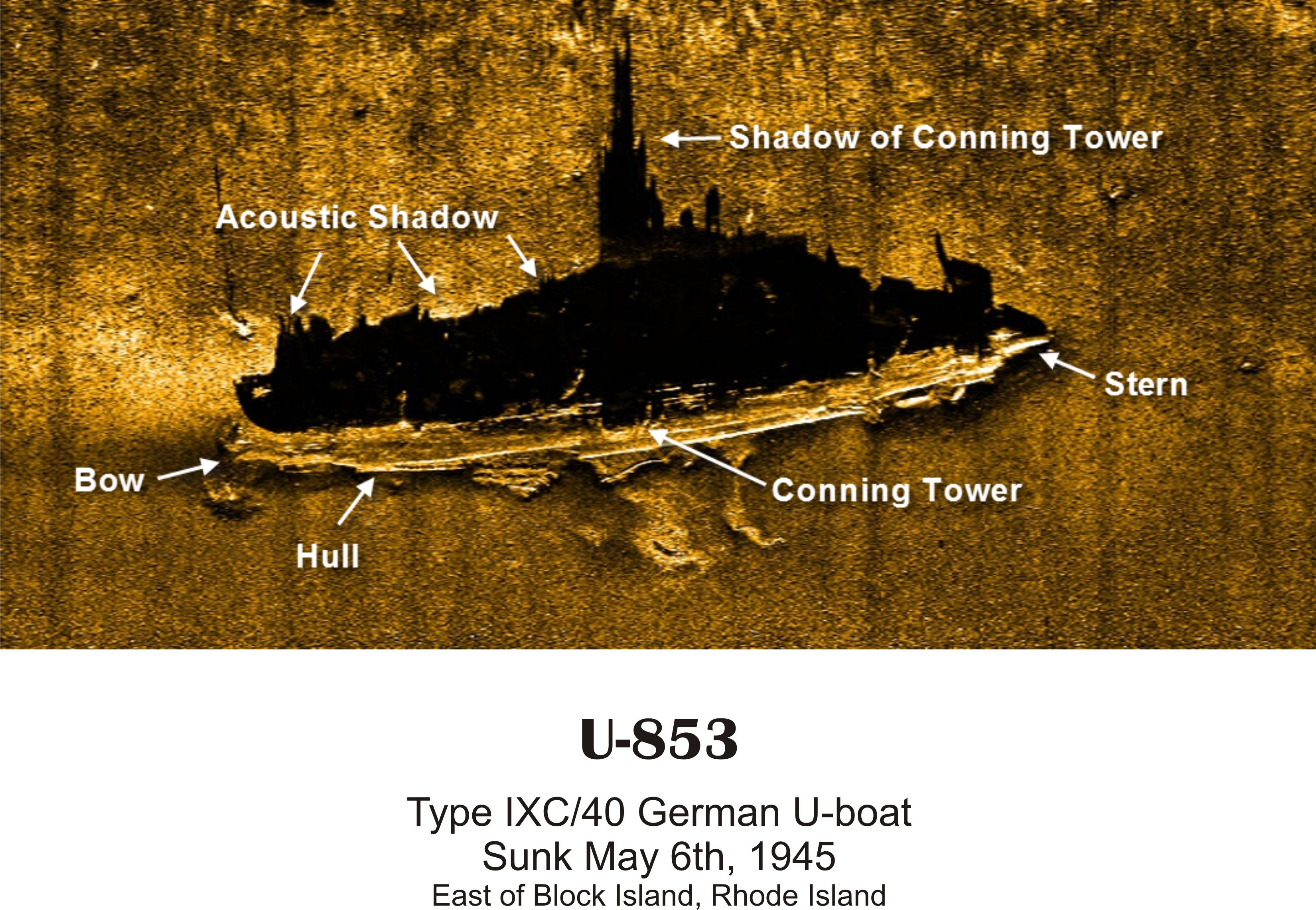

The U-853, a large German Type IXC/40 U-boat, is one of the most dived wrecks along the U.S. East Coast. By the summer of 1960, just 15 short years after the end of World War II, local “skin divers” (as they were called at that time) had already scoured the wreck site, removed the upper portion of one of the periscopes and brought up a number of “souvenirs” to include a complete human skeleton that was later returned to Germany. Its main historical draw for divers is that U-853 was the last U-boat sunk in American waters during World War II. As true as that may be, U-853’s wartime history remains distorted. The U-boat’s 24-year-old captain, Oberleutnant Helmut Frömsdorf, is often maligned in depictions of U-853’s final war patrol due to his sinking of the aging steamer SS Black Point so close to the coast on May 4th, 1945 after Führer der U-Boote im Westraum (Commander in Chief, U-Boats West) broadcast an order to cease all offensive operations earlier that day. This sinking is typically viewed as a “rash” act by a “young” naval officer seeking to risk his crew in pursuit of a “decoration” when the war was all but over. This interpretation, however, loses merit when viewed against the historical record within the context of ‘Total Undersea War’.

Frömsdorf’s actions while in command of U-853 were entirely consistent with those of hundreds of other U-boats now retrofit with a new snorkel system. Introduced in late 1943 as a defensive measure against radar equipped Allied aircraft, and retrofit into the U-boat fleet thereafter, the snorkel revolutionized submarine warfare well into the postwar world. It allowed the once surface bound U-boat to remain submerged indefinitely, evading even the best efforts to locate and destroy them. More importantly, the snorkel allowed the U-boat to return to the offensive in ways that Befehlshaber der U-Boote (Commander of U-Boats) or BdU, never intended.

The U-boat was a surface bound submersible that could only remain submerged for at most 30 hours before the oxygen onboard ran out. It needed fresh air not only for its crew, but also to run the diesel engines to recharge its batteries. By May 1943 surfaced U-boats were being detected and attacked by radar-equipped aircraft vectored to the U-boat’s position locations with coordinates from decoded signals traffic known as Ultra. The U-boat loss rate made mid-Atlantic Wolfpack operations unsustainable. Admiral Dönitz, overall commander of the U-boat force at that time, needed to find a way to enable his boats to continue the war. The solution was the snorkel. U-boat’s equipped with the snorkel no longer needed to surface to refresh the boat’s air, or to run their diesels to charge batteries. It was soon found that snorkel-equipped U-boats could in fact run their diesel engines while submerged through the snorkel increasing their underwater speed beyond what was capable on only electric motors. They rarely sent wireless signals, degrading Ultra’s value in the last year of war, and staying submerged reduced sinking’s by Allied radar-equipped aircraft by a factor of 10 almost overnight. They did not even need to use a periscope to hunt Allied vessels, often firing an acoustic homing torpedo from depth at a sound contact. Operations and tactics evolved. Gone were the days of the mid-Atlantic Wolfpacks and night surfaced attacks. By the summer and fall of 1944, U-boats operated alone into the shallow waters of the English Chanel, Irish Sea, Gulf of St. Lawrence and outside various Allied convoy embarkation and debarkations ports all along Great Britain’s coast.

Contrary to what has been portrayed in the past literature of the Battle of the Atlantic the snorkel was universally accepted by U-Boat crews. They realized during their first patrol with the device that their chances at survival dramatically increased, even in the most challenging operational areas like the English Channel, which was off limits to U-boat since almost the start of the war. Conceived initially as a defensive technology, the snorkel quickly became an effective enabler of offensive operations as crews became adept at underwater navigation, tracking and firing at sound contacts without visual identification by periscope, and the employment of ‘bottoming’ to hide from hunting Allied surface vessels by utilizing the surrounding underwater terrain.

It took about five months of snorkel-equipped U-boat operations for enough experiences to be compiled by BdU and transmitted out to the U-boat force in the form of new tactical guidance. U-boat crews were learning how to use the snorkel effectively on their first patrols, incorporating the lessons of prior U-boats’ cruises without the benefit of any pre-operational training. The snorkel, which at first was intended only to allow U-boats to stay submerged for a few days, soon allowed U-boats to remain submerged indefinitely. After six months of operational patrols against the coasts of Great Britain and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, BdU was ready to dispatch U-boats back against the U.S. East Coast in greater numbers than at any point in the previous two years.

In order to understand the significance of this last deployment to the North America’s Atlantic coast in 1944-45, it can be compared to the initial operations by U-boats against this area in 1942. During the seven months (January-July 1942) of operational Paukenschlag (Drumbeat) more than sixty German U-boats were dispatched to the North American coast. After the strengthening of US coastal defenses, the operation was ended by BdU. With only a few exceptions, U-Boats were dispatched alone to patrol the deep-water approaches off the North American continental shelf until the introduction of the snorkel. During the twenty-month period of August 1942 through May 1944 a total of 31 U-Boats were sent to patrol the deep water off the continental shelf of the North American coast at an average of 1.5 U-boats per month. With the introduction of this snorkel, U-boats began to patrol against Canada, then the U.S. East coast in greater numbers. Starting in May 1944, through the end of the war in May 1945 a total of 37 snorkel-equipped U-boats were dispatched against the North American coast, with a total of 20, dispatched in the last sixty days of the war. Of those twenty U-boats, 90% were dispatched to patrol off the U.S. East coast. This represented the highest concentration of U-Boats to deploy to the area in almost three years.

When Frömsdorf and the crew of U-853 departed on their third patrol in March of 1945 his U-boat was among a dozen enroute or already operating off the North American coast. Morale in the U-boat force at this time was high, because the sinking of U-boats during the fall of 1944 reached its lowest point since early 1943 thanks to the introduction of the snorkel. In addition, the sinking of Allied vessels also increased during the same period.

Frömsdorf actions off the U.S. East Coast have often been characterized as “reckless” and explained by referring to his “tender age”.i Yet, the average age of a U-boat captain sent against the North American coast in 1945 was 28 years old. At the age of 24, Frömsdorf was not even the youngest! Three other U-boat captains were 23 years old and in command of over 50 sailors and a 750-ton weapon system. To better understand Frömsdorf, we can look to his actions when he took over command of U-853 during a harrowing attack by Allied aircraft nearly a year earlier.

On June 16th while on its first combat patrol, U-853 was surfaced in the mid-Atlantic in order to transmit a required weather report back to BdU. U-853 was soon attacked by two Allied aircraft that dove out of the sun. The U-boat’s 29-year-old commander, Kapitänleutnant Helmut Sommer was severely wounded. Sommers turned over control of the U-Boat to his First Watch Officer, the 23-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Helmuth Frömsdorf, who was also lightly wounded. Destroyers were now in pursuit and Frömsdorf had to lead under fire as he worked to maneuver U-853 out of harm’s way. Under Frömsdorf’s leadership U-853 made its way to the Bay of Biscay and 18 days later arrived in Lorient on July 4th, safely. The crew did not know it at the time, but the hunter-killer group that included the escort carrier USS Croatan (CVE-25) was in pursuit and maintained active patrols against U-853 all the way to the Bay of Biscay. Allied intelligence had picked up the transmission from U-853 noting its losses and continued to vector the Croatan after the stricken U-Boat.i In a postwar interview USN Captain John P. Vest of the Croatan stated “you have to have got to hand it to him, he did a great job of . . . getting his boat home.” Frömsdorf did just that. His actions on the return suggest he was a competent, if not prudent, officer who effectively outmaneuvered a hunter-killer group to return his stricken U-Boat back to port. While in Lorient, France, Sommers was medical discharged as commander to recover from his wounds while U-853 received a snorkel retro-fit.

U-853, now under the command of Frömsdorf, underwent snorkel training before its planned departure back to Germany where more extensive repairs of the U-boat could occur. Before its departure, U-853 was assigned the 10th U-Flotilla commander Korvettenkapitän Gunter Kuhnke as temporary commander of U-853 during its return trip to Germany. It is likely that in practice Frömsdorf oversaw the U-boat’s transit from Lorient on August 28th through some of the most heavily defended waters around Great Britain, back to Flensburg, Germany where it arrived safely on October 14th. Once back in Flensburg, Frömsdorf officially took command of U-853 again.

The snorkel’s impact can be readily seen when U-853’s first two war patrols are compared. Both patrols were very similar semicircular routes between French and German ports. The first patrol lasted 67 days and included mandatory weather reporting, while the second lasted only 48 with the clear goal to avoid enemy contact and return to Germany for a thorough overhaul. On its first patrol without a snorkel U-853 cruised 5,869.9 nautical miles (3,760.8 surfaced and 2,109.1 submerged). This amounted to 40% of the patrol underwater. If we calculate its return patrol from Lorient to Farsund at the southern tip of Norway, where it stopped before heading south across the Skagerrak to its final destination at Flensburg, U-853 was at sea 43 days. Its cruise from Lorient to Farsund accounted for 2,409.6 nautical miles of which 1,988.6 were completed submerged. This meant that 83% of the entire return cruise was submerged—more than double the time spent underwater then on its first cruise. Frömsdorf and the crew of U-853 clearly gained valuable operational and tactical experience with the new snorkel system, remaining submerged for 18 days straight during one portion of their return journey. When U-853 departed on its third wartime patrol its commander and crew had the benefit of more snorkel experience than most U-boats that conducted their first wartime patrol with the device.

No Kriegstagbuch (KTB), or daily war diary, exists for U-853’s final patrol because it was sunk, however Ultra intercepts, Allied weekly intelligence assessments of U-Boat operations, and the prevailing tactical guidance issued by BdU provide context for what likely occurred.

U-Boat captain’s motivations were personal and varied. Frömsdorf was no different. A member of the Class of 1939, he was a new captain, but not unknown to the crew. The investigation into Frömsdorf by past researchers has often led them to rely on simple hearsay for an explanation for his actions on U-853’s final patrol. His last letter to his parents did not reveal anything out of the ordinary, except the sense of duty to his assignment that undoubtedly many his age felt at that time. A statement from Kapitänleutnant Sommer’s wife long after the end of the war has also taken on evidentiary weight far greater than its actual historical value. Sommer was a captain in the pre-snorkel U-boat fleet. Klara Marie, Sommer’s wife, penned a letter in 1974 to an intrepid researcher of U-853 that is often cited as evidence of Frömsdorf’s apparent “recklessness”. Writing from memory, Klara Marie recalled a statement made by her late husband about the sinking of U-853: “He often told me, that he never had attacked a ship in such a situation, U-853 was lost from the beginning with such little water under the keel and so near the coast.” Sommer’s statement was that of U-Boat captain who never once cruised on a snorkel-equipped U-boat. He never received the training to conduct shallow water operations that dominated the last year of the U-boat war. Sommer only understood the Battle of the Atlantic through the pre-snorkel lens of Wolfpacks and anti-convoy operations. In fact, when Sommer left command he would not have known much about the snorkel, which was treated as a classified “secret” technical capability. No one outside the U-boat force was made aware of this invention until the German public was first notified of it through a single propaganda broadcast made a few months before the end of the war. Sommer’s statement on Frömsdorf’s final action is an uninformed opinion, not a credible piece of historical evidence. A significant shift in U-boat tactics was issued on December 4th, 1944 in BdU’s Current Order No. 4. The order stated in part “If no prospects of success exist in the original area of operation, [the captain] may seek out another area. For example, to run closer to the coast, to penetrate deeper into the bays, and thus occupy the apparently more difficult areas.” Clearly official guidance from BdU to the snorkel-equipped U-boat force directed action close into the coast, contrasting the statement made by Sommer to his wife.

U-853 departed Norway on February 23rd for its patrol to the North American coast. Its orders, recorded on April 1st, 1945, were clear: “Gulf of Maine as operations area, focal point off Boston. If unfavorable, alternative area Halifax or New York.” By mid-March there were more than a dozen U-Boats enroute or operating off the U.S. East Coast with one operating off Nova Scotia. BdU broadcast two intelligence reports to these U-Boats outlining Allied defenses around Cape Hatteras and Halifax. With so many U-Boats deployed to the U.S. East Coast for the first time in nearly three years, many of which were not transmitting wireless messages that could be triangulated through direction finding, confusion entered into the ability for Allied intelligence to track them all. In addition, not all U-boat ciphers in the last year of war could be read through Ultra. In the case of U-853, Allied intelligence never assessed that U-853 was assigned the Gulf of Maine as its initial patrol area. Specifically, it was not clear as to which operational area the U-boat was destined and Allied intelligence incorrectly identified Cape Hatteras as U-853’s operational area.

As Frömsdorf set course for the port of Boston, Allied intelligence incorrectly identified U-853 as the U-Boat that arrived off Cape Hatteras on April 14th and sunk a number of Allied ships. Unknown to Allied intelligence at that time was that two other U-Boats were assigned to Cape Hatteras, and likely involved in the reported attacks. The confusion in Allied intelligence assessments has much to do with the lack of U-Boat radio communications, which was common place after the introduction of the snorkel.

As Allied intelligence believed U-853 was operating off North Carolina, a sinking occurred in the Gulf of Maine 18 days later on April 23rd when the patrol boat USS Eagle PE-56 was torpedoed three miles south-southeast of Cape Elizabeth, Maine. The 430 ton Eagle was towing targets for US Navy bomber exercises when it was struck amidships with a heavy explosion, broke in two and sank. The commander, four officers and 44 enlisted sailors were lost, while one officer and twelve enlisted sailors were picked up about 30 minutes later by the USS Selfridge (DD 357). The Selfridge immediately began to drop depth charges on a nearby sonar contact.

Allied intelligence never recorded the destruction of the USS Eagle as sunk by a U-boat during the war as the US Navy initially determined it was a boiler explosion at that time. Not until 2001 did the US Navy determine that the USS Eagle was indeed sunk by U-853 based on dogged detective work by Attorney Paul M. Lawson who identified testimony by several survivors who reported briefly sighting a U-Boat’s conning tower with the same orange and red colors of the ‘Golden Horseshoe’ emblem that adorned the tower of U-853. U-853 easily prowled in the Gulf of Maine undetected through the tactic of “bottoming”, whereby a U-boat rested among the rocky underwater terrain that obscured sonar detection. This was a tactic broadcast out to the snorkel-equipped U-boat force by BdU as early as July 1st, 1944 in Experience Message 113 titled “Silent Trim”, which was reinforced multiple times through the fall of that year. While the seabed terrain in the Gulf of Maine offered U-853 protection from surface sonar, it likely adversely impacted U-853’s underwater detection ability, and Frömsdorf was unable to identify further viable targets. Frömsdorf likely remained in the Gulf of Maine for about 5-7 days before deciding to make his way southward to the New York, as specified in the second part of his orders.

U-853 cruised down the coast, passing Cape Cod, Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, finally entering close inshore near Block Island. The order from U-boat command to cease all U-Boat operations was first broadcast on May 4th. Did U-853 receive this initial order? It appears unlikely based on what is now known regarding communication problems associated with snorkel-equipped U-boats. What has been previously unknown, is that wireless communications became a major problem with snorkel-equipped U-boats that maintained near continuous underwater patrols. BdU broadcast out a Top Secret message in November 1944 known as Current Order No. 80 “Causes of bad wireless communication” that stated in part “Bad transmitting conditions are not only caused by bad atmospheric conditions, but according to recent experience, by state of the aerial apparatus. Long snorkel cruises make heavy demands on the aerials.” Allied intelligence noted that among snorkel-equipped U-boats “Great difficulty is being experienced with radio transmissions in the middle and western Atlantic . . . .” Further to the point, wireless reception onboard a submerged U-boat diminished the deeper it cruised. As U-853 was almost certainly cruising submerged, Frömsdorf, at best, might have heard a garbled or partial transmission that was not understood.

While we do not know with certainty what U-853 was doing on May 4th because no KTB exists, we do have the operational guidance and tactical precedence issued during the period of ‘total undersea war’ to reconstruct Frömsdorf’s final actions. U-853 likely snorkeled sometime between midnight and 4:00am for about an hour, as dictated by current guidance, to recharge batteries and refresh the boat’s air. Given the thick fog that morning that halted surface traffic, Frömsdorf likely bottomed his U-Boat in the shallow water between Sandy Point, Block Island and Point Judith, Rhode Island to await a sound contact in the coastal waterway between New York and Boston.

That same day the SS Black Point, a 5,353 (GRT) aging collier loaded with coal, was enroute to Boston from Norfolk. It was following a well-traveled coastal route from New York City to Boston via the Long Island Sound, Rhode Island Sound, and the Cape Cod ship canal. This was a natural choke point for shipping that was likely known to Frömsdorf. His decision to stalk this route was consistent with similar tactics pursued by U-Boats off the coast of Great Britain. The Black Point maintained its position at anchor during the period of fog that morning as its captain, Charles E. Prior, did not want to run the risk of hitting another ship. The morning fog in these waters can be exceeding thick as I personally experienced on my first dive upon U-853 in 2015. When the fog burned off on May 5th, the Black Point was greeted with sunny, blue skies and moderate seas. Captain Prior gave the order “Full Ahead” and the Black Point’s screws began to turn as the ships engines came to life.

The Black Point’s screw was identified in the hydrophone room onboard the bottomed U-853. Frömsdorf likely gave the order to lift off the sandy bottom, engage his electric motors, and set a course toward the sound contact. Sometime later a T5 acoustic homing torpedo was fired from a depth of 30 meters while U-853 remained below the surface as per Current Order No. 67 “Firing torpedoes on the basis of firing data obtained by hydro-phones” issued in November 1944 to the snorkel U-boat fleet. i At 5:40pm on May 5th, two miles off Point Judith the stern of the Black Point was blown off.

There was nothing unusual about an attack so close to shore by a snorkel-equipped U-Boat off the U.S. East Coast. Such tactics were utilized by hundreds of U-Boats operating on both sides of the Atlantic over the past 10 months with a high-degree of success. Orders by BdU directed such tactics as in Experience Report No. 152. also issued in November 1944, that stated “behavior after firing torpedoes, especially in the vicinity of the coast: move away from the place of firing and then, but not until then, lie on the bottom in order to escape direction-finding and hydrophone pursuit.” In order to constantly change tactics and confuse Allied Escort commanders, BdU altered its guidance accordingly. While we cannot know if Frömsdorf received the following transmission, BdU issued a new Experience Message on March 2nd 1945 that stated in part “Do the opposite from what the enemy expects of you, for instance, move off into shallow water. They have added no new tricks to their defense.”

The tactical situation Frömsdorf found himself was expected of a snorkel-equipped U-Boat during the period of ‘total undersea war’. U-853 was in about 39 meters of water. Frömsdorf knew his shallow depth and that deeper water was 50-60 miles to the east where the 100-meter line was located. But Frömsdorf had no reason to be concerned or feel compelled to head for deep water. He had identified no Allied escorts in the area. Had Frömsdorf known that US Navy Task Force 60.7 was thirty miles away enroute to Boston for supplies, he might have either bottomed near the Black Point or headed closer inshore. U-853 might well have escaped the coming retribution to surrender as a number other U-Boats did off the North American coast. What we do know is that U-853 briefly surfaced, then headed south toward Southeast Point, Block Island.

The sinking of the Black Point after the initial order to cease combat operations should not be interpreted as a “reckless” act on the part of Frömsdorf when compared against the training and tactical guidance issued to the snorkel-equipped U-boat fleet. Further evidence suggests that Frömsdorf simply did not receive the initial transmission. As the message was being repeated, he might have picked up a garbled rebroadcast, especially if U-853 rose to periscope depth to inspect the stricken Black Point. The strongest evidence to support this interpretation of Frömsdorf’s action comes from a report by the crew of the Yugoslav flagged freighter SS Karmen that rescued the survivors from the Black Point.

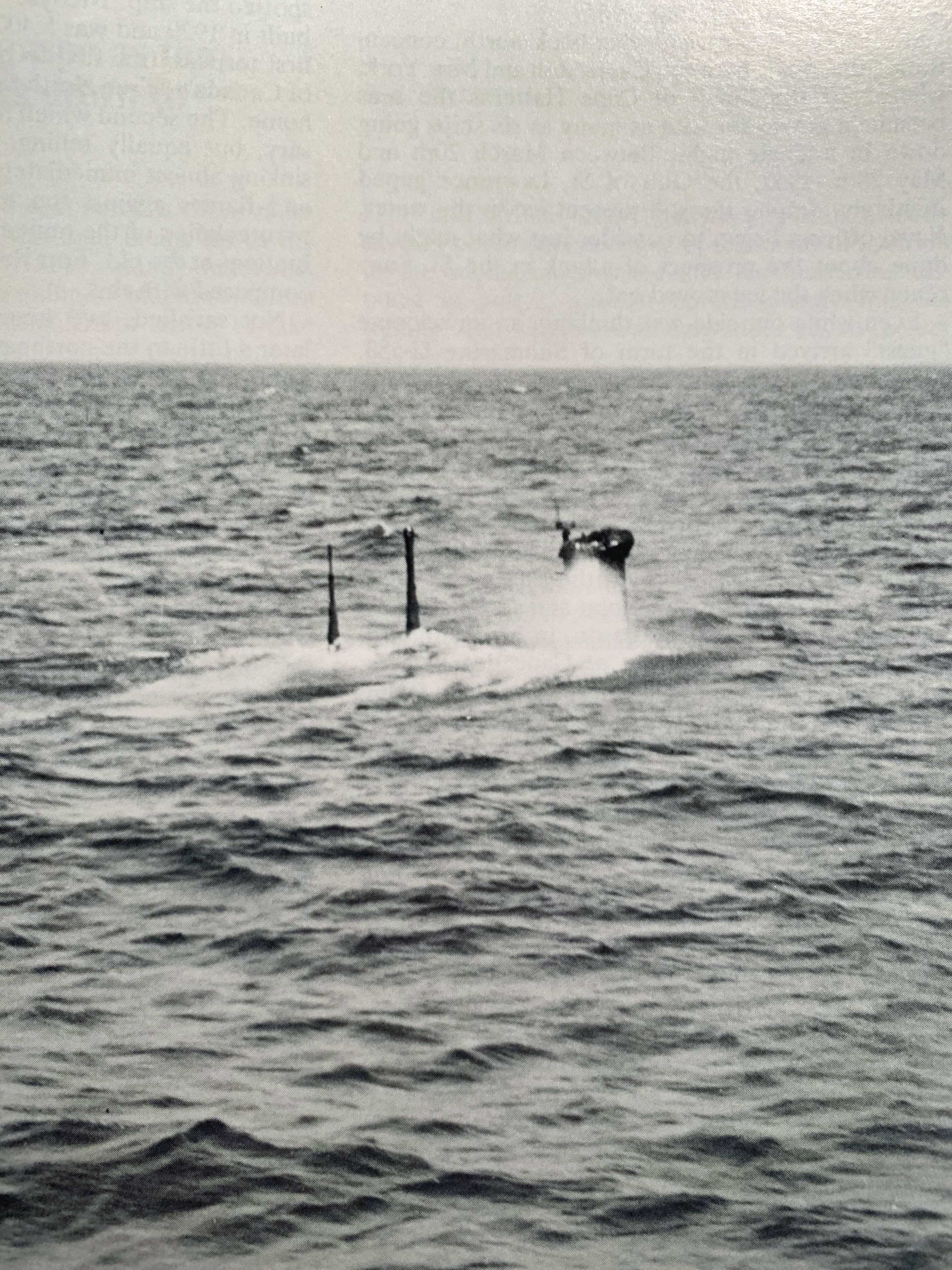

Witnesses onboard the Karmen reported seeing U-853 surface. They observed several crew members emerge from the conning tower, head to the “aft deck” and attempt “to deploy a yellow inflatable raft.” Within moments, the crew scrambled back down below deck and submerged. What was the crew attempting and why did they quickly retreat back into the U-Boat and submerge? Given both the color and texture of the observed item, U-853’s crew was very likely attempting to send up an Aphrodite anti-radar balloon. U-Boats that had trouble sending or receiving wireless messages attached a copper wire that was hooked up to the auxiliary radio in the conning tower and sent the balloon aloft to be able to improve transmission and reception back to BdU. Other Type IXs operating off the North American coast deployed this device as in the case of U-541 operating off Canada in September 1944 and U-1233 operating off the U.S. East Coast in January 1945. This solution was recommended by BdU and became standard practice in the snorkel-equipped U-boat force. It is almost certain that Frömsdorf was trying to boost his wireless reception by sending aloft an Aphrodite balloon, perhaps to send a message back to BdU to confirm the order to cease combat operations. Frömsdorf, however, spotted the nearby Karmen or picked up its S.O.S. message and quickly ordered U-853 submerged. A course was plotted to take the U-boat out of the area, to the southeast around Block Island.

U-853’s action on May 5th was not unique, nor was this the only U-boat operating so close to the North American coast. As late as May 14th Allied intelligence was tracking the surrender of U-805, and U-190 that had yet to fall under escort of an Allied vessel. U-873, U-1228 and U-858 had just reached their assigned surrender points and fallen under escort. U-889 just arrived at Shelburne, Nova Scotia. U-234 had not responded to any hourly radio calls to surrender and was still being hunted aggressively by USS Milledgeville (PF-94).v Of particular note is that on May 4th U-530 was operating off the shallow coastal waters along Long Island, near the approaches to New York City, and fired a spread of three torpedoes that missed their target. Two days later U-530 repeated an attack, but missed again. On May 7th, three days after the order to cease hostilities was broadcast U-530 again fired two more torpedoes at another convoy, but scored no hits. Frömsdorf’s sinking of the SS Black Point cannot be viewed as some “suicidal” act under the circumstances, nor was his U-boat the only one experiencing wireless reception issues. It was only fate that intervened and prevented U-530’s torpedoes from striking an Allied vessels days after the Black Point was sunk. If U-530 did sink a ship after the U-853, how then would Frömsdorf’s final combat patrol be remembered?

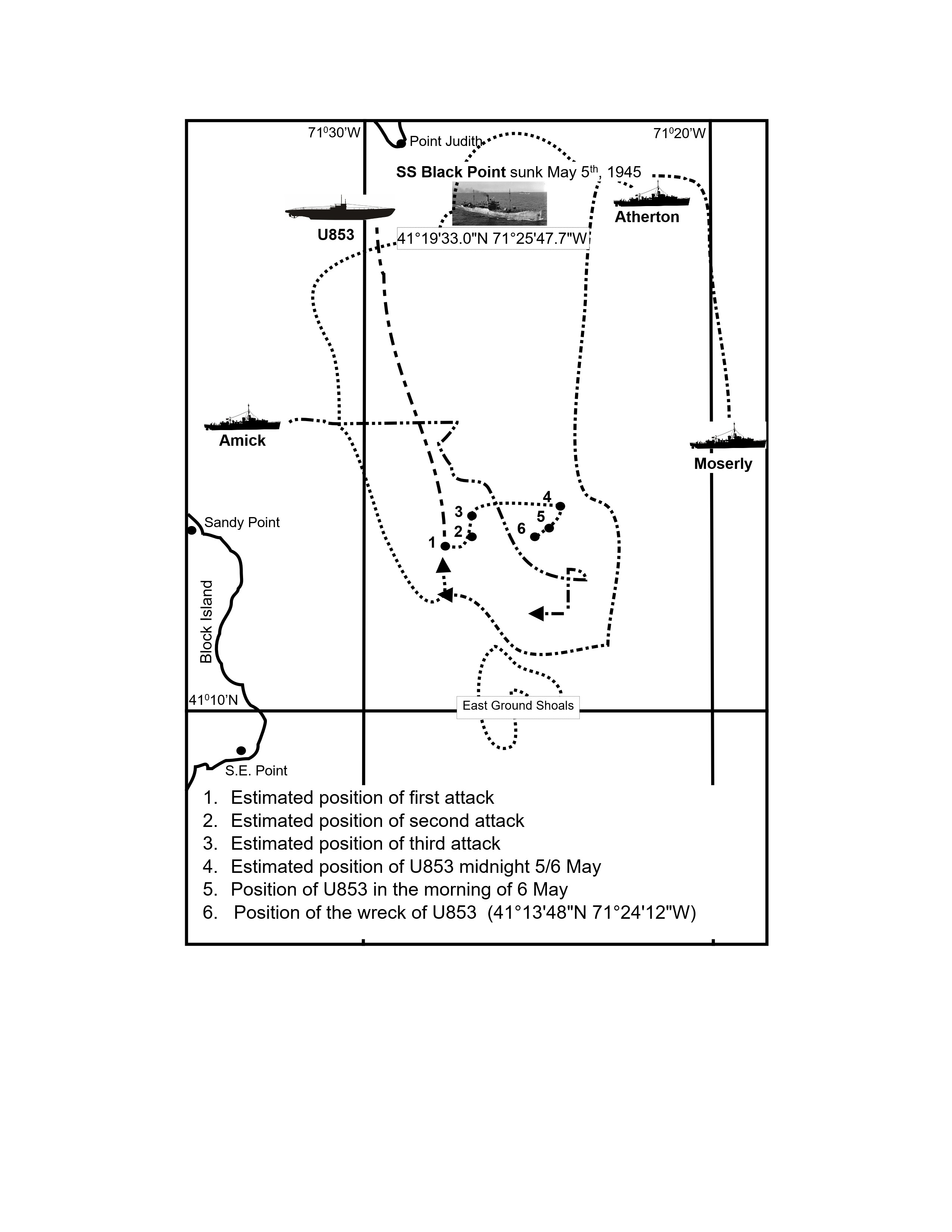

Even the final account of U-853’s sinking was prone to confusion and led some to believe that Frömsdorf was running for deep water after being caught unprepared in the shallows off Block Island causing some to wonder why his U-boat was operating in such shallow water. Three escorts that made up the remnant of US Navy Task Force 60.7 were only thirty miles away bound for the Navy Yard in Boston for routine maintenance and supplies. These ships consisted of two US destroyer escorts, USS Amick (DE-168) and USS Atherton (DE-169) as well as the U.S. Coast Guard operated patrol frigate USS Moberly (PF-63), which had picked up the S.O.S. signal sent by the Karmen. Command of the U-Boat search immediately fell to Lieutenant Commander L.B. Tollaksen, USCG, of the Moberly.

Tollaksen notified the two destroyer escorts of the S.O.S. and ordered Atherton, who was in the lead, to head toward the site of the sinking and sweep south, while the Amick, who was second in column, to sweep the western approaches to the sinking site. By 7:30pm all three search vessels formed a line about 3,000 yards abreast at the northern tip of Block Island and began a southward sweep. New shallow water U-boat tactics were generally known to US escort commanders from their Royal Navy and Canadian counterparts who gained vast experience against snorkel equipped U-Boats. However, US commanders had no such practical experience along the U.S. East Coast. What Tollaksen knew was that as part of these new tactics, a U-Boat would likely “bottom” near a shoal or a wreck in order to mask its acoustic signature and avoid detection.

Tollaksen assessed Frömsdorf’s next action correctly. However, a postwar interview with then Lieutenant Commander Lewis Iselin, Atherton’s commander who is credited with the U-853’s destruction, is often used to explain the search tactics that resulted in the U-Boat’s location. Iselin stated that “I use my experience. I felt he would be making for deeper water and I caught him before he got there. It was just damn good luck on my part not his.” Iselin’s memory of that search and U-853’s final action is likely incorrect. A 1960 article about the destruction of the U-853 was written by Ensign D. M. Tollaksen, USN, who was the son of L.B. Tollaksen, the acting onsite search commander. He had access to his father’s notes and recent memory of those events and wrote a more accurate assessment of the search. According to the younger Tollaksen:

The search was planned on the assumption that the submarine would try to run out of the area at high speed until the skipper felt he could safely lie on the bottom for the night. [Author’s emphasis] It was believed that she would not get very far as she would want to keep a reserve charge in her batteries. About nine miles to the south of Black Point was an area which might be chosen by the submarine as an excellent place to hide. In this area, known as East ground, there is a steeply rising shoal alongside of which a submarine might be able to lie and escape detection of any searching destroyer. In addition there was the possibility of a wreck in the area which would further confuse the search. Such tactics were the latest in use by German U-Boats. Once the above course of action was deemed most likely for the German submarine skipper to follow, the search plan was set up to sweep across the area and back. [Author’s emphasis]

The senior Tollaksen correctly assessed Frömsdorf’s actions based on new shallow water U-boat tactics and caught U-853 on the low-relief seabed accordingly just north of the shoals.

This was now the first hunt for a U-Boat using such tactics in US coastal waters. Frömsdorf in fact headed south toward the shoal, and not due east or southeast toward deeper water as Iselin claimed in his later years. Unfortunately for Frömsdorf, the shallow coastal waters south of Block Island were smooth and sandy, and offered no protection from the constant pinging of active surface sonar that the Gulf of Main’s rocky seabed provided. Frömsdorf then turned the U-boat and headed north, then east, likely in an attempt to throw off his pursuers, before turning back to the southwest again. U-853 was caught and sunk on May 6th, 1945, the first and last such U-boat to employ these tactics in North American waters during a surface anti-submarine hunt.

In evaluating the final war patrol of U-853 within the historical framework of “total undersea war,” Frömsdorf’s actions were not the reckless behavior of a “suicidal” commander, but were consistent with the new guidance issued by BdU. The introduction of the snorkel that ushered in an evolution of submarine operations and tactics late in the war were as deadly and tragic to the men lost on USS Eagle and SS Black Point, as they were to the crew of the U-boat that sunk them.

About the Author

Aaron Stephan Hamilton is an academically trained historian. He holds both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in history, as well as the Field Historian designator awarded by the U.S. Army’s Combat Studies Institute. He is an amateur maritime archeologist with a focus on submarine history. For more than twenty-five years he has researched and published ground-breaking studies about the final year of World War II in Europe.

Total Undersea War is available to preorder here.