As Fate Would Have It

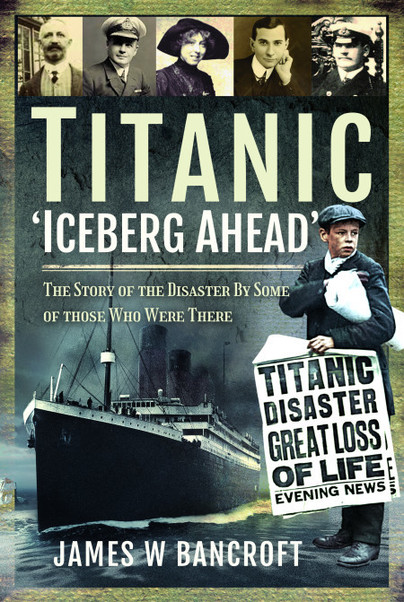

Guest post from author James W Bancroft.

As Fate Would Have It

Arthur Gee – Titanic Victim

Arthur Gee came from a family of printers, and early in April 1912 he had organised a trip across the Atlantic to take a job as manager of a linen mill near Mexico City, after which he was contemplating retiring. He intended to sail from Liverpool, but because industrial unrest had affected the port there the ship was delayed and, as fate would have it, he happily agreed to travel to Southampton to board the brand new luxury liner RMS Titanic.

However, as the local Lytham St Anne’s newspaper reported: ‘He kept a dog, which usually reserved its most affectionate demonstrations for Mr Gee’s children. Mr Gee, in the course of his business, made frequent journeys from home, but his going and comings were apparently regarded with unconcern by the dog. On the occasion of his departure to embark at Southampton, however, the dog followed the cab to the railway station, and at the station jumped about Mr Gee in so demonstrative a fashion that he remarked on the strangeness of the incident to a friend who was seeing him off, and said how remarkable it was that the dog should appear to know that he was going on a long voyage.’

Arthur Henry Gee had been born on 21 March 1865, at 25 Bolton Road, Irlams o’ th’ Height, Pendleton, Salford, the son of Giles Gee, who was a calico print dyer, and his wife, Amelia (formerly Crosby). He had three older siblings. He was taken to Russia by his parents when he was three, and spent his early years at Schlusselburg near St Petersburg, where his father was employed at the local calico printing works. At the age of fourteen he came back to live in Salford for the purpose of pursuing his studies at the Manchester Grammar School, and he attended the United Methodist Sunday School. He was also a member of the chapel choir. His father sent him to Alsace in Germany to study the chemistry of calico printing, and while he was there he learned to speak French and German. After finishing his studies he returned to Schlusselburg, where he was employed at the calico printing works, working his way up to become the manager.

On returned to England in about 1911 he settled at a house named ‘Morningside’, in Riley Avenue, St Anne’s-on-Sea, Lancashire, with his wife, Edith, and his fifteen year old daughter and three younger sons. He took employment as a representative for the firm of Whitehead, Sumner, Harker and Company, a machine exporters based on Deansgate in Manchester. He enjoyed playing golf on the St Anne’s Old Links Golf Course.

On his arrival at Southampton he was obviously impressed by the ship, and in a letter written on White Star Line stationary while the ship was docked at Queenstown, which has survived, he wrote:

‘My dear,

In the language of the poet, ‘This is a knock-out.’ I have never seen anything so magnificent, even in a first class hotel. I might be living in a palace. It is, indeed, an experience. We seem to be miles above the water, and there are certainly miles of promenade deck. The lobbies are so long that they appear to come to a point in the distance. Just finished dinner. They call us up to dress by bugle. It reminded me of some Russian villages where they call the cattle home from the fields by horn made from the bark of a tree. Such a dinner! My gracious!’

During the voyage Arthur kept a diary in the form of an eight-page letter, which records the daily mileage of the ship, details about the food and the people he met. He records that on 13 April he was moved to another cabin by a steward because he wanted a porthole. The cabin was arranged for four people, with two wardrobes, large sofa, chest of drawers, three electric lights, electric fan and heater. The porthole was fifteen feet from the water line.

On the night of 15 April 1912 he had dined with Purser McElroy, after which he retired to the first class smoking room and sat with two businessmen, an American named Charles Jones, and a Yorkshire man named Algernon Barkworth. As the clock approached midnight there was a loud bang and scraping noise, and they were soon informed that the ship had hit an enormous iceberg.

Barkworth stated: ‘Coming over I made the acquaintance of two most agreeable chaps …The other man was A H Gee. I was discussing in the smoking room with them late on Sunday night the science of good road building in which I am keenly interested. When the crash came somebody said we had hit an iceberg, but I didn’t see it. Jones and Gee were looking over the side. I learned swimming at Eton and made up my mind if it came to the worst I would try my luck in the water. When the ship gave the first dip we all went aft. Well, I had read somewhere that a ship which is about to sink gives a premonitory dip, and when the Titanic did that I simply chucked my despatch case, containing all my money and some papers, into the scuppers, Jones and Gee were standing by, with arms on the rail, looking down. I imagine they were preparing for death.’

Arthur was reported to be a strong swimmer but he drowned in the sinking. His body was number 275 recovered from the water by the rescue ship Mackay-Bennett, being described as aged about 60, although he was actually 47, having dark hair and a moustache. He was wearing a brown overcoat, with a tuxedo suit and dress pants. His effects were a silver watch, gold chain, silver cigarette case, various small items and some banknotes.

Arthur’s remains were transported to Liverpool on the Baltic. His funeral took place on 18 May at St John’s Church, on the Height in Salford, and he was buried in the grave next to his father. The gravestone stood for some time but has now been removed and the area has been grassed over.

Titanic: ‘Iceberg Ahead’ is available to order here.