Author Guest Post: James Goulty – An Airborne Soldier at War and Peace

Bill Ness 12th (Yorkshire) Battalion Parachute Regiment

Today we have a guest post from Pen and Sword author James Goulty… Enjoy!

Towards the end of

the First World War General William Mitchell, the noted air power

theorist who commanded the US air forces in France during 1917-18,

proposed the dropping of men from 1st

US Infantry Division behind the German lines. However, the plan was

shelved before it could be put into effect because the war ended.

Subsequently, demonstrations of the deployment of paratroopers were

held in the US but failed to receive official backing.

In contrast, in

1927 the Soviet Union was the first nation to deploy paratroopers in

an active combat role during operations against tribesmen in Asia,

and during the 1930s went on to establish an independent parachute

division. Developments in the Soviet Union had been observed by an

amazed Field Marshal Wavell, who later became the Commander-in-Chief

in the Middle East and then India. Yet the War Office in Britain was

slow to fully appreciate the potential of airborne forces.

The concept

received renewed consideration with the onset of the Second World War

when the British authorities were alarmed by the dramatic successes

of German airborne units, forged under the direction of General Kurt

Student. In April 1940 these undertook an extensive part in the

invasion of Norway and Denmark, and were later deployed against

targets in Belgium. The Germans even envisaged that approximately

8,000 paratroopers would be used in the initial wave of Operation

‘Sealion,’ their proposed invasion of Britain.

On 22nd

June 1940, the Prime Minister (Winston Churchill) issued an

instruction to the Chief of Staff calling for the establishment of ‘a

corps of at least five thousand parachute troops.’ By the end of

that year General Sir Frederick Browning had been tasked with raising

a fully functioning airborne division. This required the necessary

logistical support and training organisation. Under the control of

the RAF the Central Landing Establishment was formed at Ringway that

comprised a Development Unit, Glider Training Squadron and Parachute

School. Eventually, the British Army was able to field two complete

airborne divisions during the Second World War. The 1st

Airborne Division gained extensive operational experience in North

Africa and Italy, prior to famously being deployed at Arnhem as part

of Operation Market Garden in September 1944. The 6th

Airborne Division, with which Bill Ness served, was formed in Britain

during 1943, and deployed on D-Day and in North-West Europe during

1944-45.

Bill was born and

bred in Byker, Newcastle upon Tyne and left school at 14 years old to

go and work for the Co-Operative Stores. He had originally wanted to

be a plumber but his mother insisted that the Co-op offered steady,

secure employment. As Bill recalled ‘in those days you didn’t

argue with your parents and you did as they said.’ He was working

for the Co-op at the start of the war, but once he was 17 years old

he joined his local Home Guard unit.

Contrary, to the

image portrayed by the popular BBC TV comedy ‘Dad’s Army,’ the

Home Guard was not entirely populated by bungling idiots, although

its early days were pretty chaotic while it was still classed as the

Local Defence Volunteers. It was primarily intended for local defence

against the threat of enemy seaborne and airborne invasion. However,

as the historian S. P. Mackenzie explained, once that threat

diminished, the Home Guard increasingly became a valuable source ‘of

stand-in troops’ at a time when Britain’s overall manpower pool

was depleted. Notably Home Guard units were especially useful in

manning ant-aircraft guns and rocket batteries with Anti-Aircraft

Command.

For Bill membership

of the Home Guard proved an ‘inspiration.’ As a young lad it

brought him into contact with several old soldiers, many of whom were

veterans of the First World War with several medals. These men taught

him a lot about army life, including respect for authority and that

you didn’t question orders. As Bill explained, ‘always do as you

were told. If you couldn’t salute smartly turn-about and just

disappear.’ Similarly, he came to appreciate that ‘if you

received an order that you knew was stupid, once again salute smartly

and disappear. Never argue with anyone of superior rank. I learnt

that before I went into the army.’

The Home Guard also

gave Bill a foundation in basic military skills such as discipline,

drill, handling small arms, fieldcraft and elementary tactics. As the

Home

Guard Manual 1941

stressed the aim was ‘to have available an organized body of men

trained to offer stout resistance in every district, and to meet any

military emergency until trained troops can be brought up.’

During 1942-43 Bill

joined the army and was posted to Number 4 Infantry Training Centre

at Brancepeth Castle, County Durham. This provided recruit training

for the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment which he wanted to join, and

the Durham Light Infantry. At the ITC all drafts underwent a six week

course designed to turn civilians into soldiers. Bill remembered that

it taught you ‘the rudiments of army life,’ although he had

already experienced much of this with the Home Guard. There followed

a further ten weeks of infantry training with the Duke of

Wellington’s Regiment, after which Bill was officially classed as

‘a trained soldier.’

Bill and a

comrade from Sheffield were held back owing to their young age.

However, both were granted the rank of unpaid lance corporal with the

Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. This was an unsettling time for

Bill. Although he had successfully completed his training, he

considered that he was too young and inexperienced for the role and

responsibility he had been given. ‘Sometimes I was in trouble for

overstepping the mark, other times I was in trouble for not stepping

over the mark.’

When a company

commander from 12th

(Yorkshire) Battalion Parachute Regiment visited Bill’s unit

seeking personnel for training as airborne soldiers he and his pal

from Sheffield were enthusiastic and volunteered. The 12th

Battalion became part of 5th

Parachute Brigade that was assigned to the 6th

Airborne Division, formed in the summer of 1943 under the command of

General Sir Richard Gale. The British organisation stipulated that

each airborne division should have two parachute brigades and one

air-landing brigade as their main components. This was because as

General Gale emphasised, ‘parachute infantry by their nature were

lightly equipped, possessing neither anti-tank guns nor mechanical

transport, both of which the air-landing battalions carried in their

gliders. These more heavily equipped troops were of particular value

in defence and gave depth to the general tactical layout.’

Initial airborne

training occurred at a camp near Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, which

was comparatively close to the Central Landing Establishment at

Ringway on the other side of the Pennines. According to Hilary

Saunders in The

Red Beret,

his history of the wartime Parachute Regiment, Hardwick ‘became for

the parachute soldier ‘‘what Caterham is to the Brigade of

Guards, a place of trial but not of error.’’ Bill found it

completely different from his earlier training with a much stronger

emphasis on physical fitness. There were also night exercises, often

in poor weather, with little or no time to rest before staring work

the next day. As he put it they really ‘took you to the limit.’

Essentially the training was designed to foster toughness, physical

fitness, initiative and common sense that were vital perquisites for

the airborne soldier to possess.

After this,

parachute training commenced at Ringway, which ultimately entailed

jumping from balloons and aircraft. It was important for men to

overcome their fear, particularly when hurling themselves out of an

aircraft, and arguably this was one of the greatest challenges facing

most volunteers. Years later Bill admitted he sometimes found his

training scary, although he came through it.

One aspect that he

didn’t like was when learning the technique of parachute jumping

and landing using a machine. ‘You put a belt on and as you jumped

it started reversing while you jumped before easing up just as you

hit the ground and rolled over.’ This was probably what Hilary

Saunders described as the ‘Fan.’ A ‘steel cable, wound around a

drum was attached to the harness of the jumper, who then leapt from a

platform’ about 25 feet high onto a mat. The jumper’s weight

caused the drum to revolve, ‘but its speed was checked by two vanes

or fans, which revolved with it and thus created an air break.’ The

idea being that a soldier would land with about the same force he

would encounter during a real parachute jump.

During training

aging Whitley bombers were predominately used to drop parachute

troops, although later in his service Bill encountered the Stirling

bomber and Dakota. In general the latter was preferred because as a

purpose built cargo aircraft with a side entry/exit door it made the

whole business of parachute drops much easier to accomplish than when

using bombers converted for the role. According to one soldier quoted

in By

Air into Battle the Official Account of the British Airborne

Divisions,

on jumping from an aircraft ‘your legs are immediately blown into a

horizontal position by the slipstream and you find yourself parallel

to the ground.’ Then there is a ‘nibbling feeling at your

shoulders’ just as the canopy opens with a jerk.

Bill encountered

one night drop during training which proved very ‘queer as

everything was still.’ Also he vividly recalled one of the RAF

parachute instructors, a flight sergeant, who stated ‘it doesn’t

matter if you fall out now you’re up as high as you can go.’

These parachute instructors were often characters and came from a

variety of backgrounds. Ultimately they proved the unsung heroes in

the creation of Britain’s wartime airborne forces owing to their

important training role.

Men could refuse to

jump during training without disgrace. However, once they had

completed seven jumps and received their wings, it was an offence to

do so, punishable by at least 56 days detention, and the ignominy of

having their wings stripped off in front of their commanding officer.

Having passed

parachute training and earned the right to wear the much coveted red

beret which had been adopted by airborne units, Bill together with

several soldiers from the Green Howards was posted to barracks at

Lark Hill. Here trained infantrymen such as Bill formed a cadre for

‘C’ Company 12th

Battalion Parachute Regiment as it was being brought up to its war

establishment.

He soon became

accustomed to a morning drink of ‘gunfire’ or tea and numerous

training schemes. This included runs in full kit or G.1098, and

culminated in major exercises that were to prepare his unit for its

eventual deployment on D-Day (6th

June 1944). One of the tasks that had to be mastered was conducting

parachute jumps with men and specialised containers that carried

weapons and ammunition. Given that parachute troops were by their

nature comparatively lightly equipped, this was particularly

important for them to perfect. It was not helped by the design of

containers many of which split open on initial exercises. Bill

recounted that it was vital to synchronize proceedings and have men

and containers in the correct place so they didn’t collide on a

drop. ‘Numbers 1 to 5 would jump, followed by container, container,

container and then number 6.’ It became possible to drop weapons

such as Bren guns and two-inch mortars in these containers, plus

ammunition. A bag was also used that could be connected to

parachutists and was capable of holding supplies of around 100 pounds

in weight.

On D-Day the 6th

Airborne Division was intended to be deployed in a five-mile strip

between the Rivers Orne and Dives to secure the left flank of the

seaborne landings, particularly against the threat of counter attack

by German armoured reserves located in the Caen area. David Howarth

in Dawn

of D-Day

neatly sums up the Division’s plan as follows:

12.20 A force in

gliders to land on the Orne and canal bridges.

12.20 Pathfinders to

drop by parachute, to mark out dropping zones for the main parachute

forces.

12.50 Main parachute

drop to begin. Objectives: to demolish the Dives bridges, reinforce

the defence of the Orne and canal bridges, capture a coast defence

battery, seize the territory between the rivers, and clear landing

zones for the main glider force.

3.30 Main force of

72 gliders to land with anti-tank armament, transport and heavy

equipment.

As part of this

overall plan 5th

Parachute Brigade under Brigadier J. H. N. Poett, were to land north

of Ranville and capture the crossings over the Orne and Caen Canal

near the villages of Benouville and Ranville. The Brigade was then to

secure and hold the area around these villages and Le Bas de Ranville

which was the target of the 12th

Battalion. It was also necessary to clear and protect the landing

zones near Benouville and Ranville so that the gliders transporting

the rest of the Division could be landed safely later in the day.

As Bill prepared to

exit the Stirling bomber which had flown him to Normandy on D-Day, he

remembered thinking ‘the sooner we get out the better.’

Fortunately they hit the correct drop zone and with a sense of relief

he began to recover from the jump and remove his parachute. ‘Wait

till my mother finds out where I am. She will go bloody mad and give

me a right coating!’

To help troops

organize on the drop zone 12th

Battalion had a soldier who would use a policeman’s whistle but

unfortunately he was killed during the landing. Even so, Bill soon

found himself ‘at the back of Ranville looking towards Caen.’ Le

Bas de Ranville was taken comparatively easily and there the

Battalion was able to rendezvous with numerous of its soldiers who

had landed outside the drop zone and using their initiative made

their way to the objective instead of attempting to find the drop

zone. Having established a defensive perimeter, at dawn elements of

‘C’ Company under Captain (later Major) J. A. N. Sim engaged

German units, including formidable self-propelled 88mm guns in an

intense action for which he subsequently was awarded the Military

Cross.

During the fighting

that followed their landing, Bill recalled having to cover a flank

with his mate ‘Stoney’ on the Bren gun. They were directed by

Sergeant Milburn from Greenside, who was awarded the Distinguished

Conduct Medal for his part in the fierce fighting with Captain Sim,

and was described by Bill as ‘a sergeant of the old school.’

Later Bill was given the job of acting as runner tasked with taking

messages to Brigade HQ. He heard wail of the pipes as Lord Lovat’s

Commando unit landed on the coast, not that far from where they were

operating, although they were beyond visual range.

Bill’s unit later

had to advance by leap frogging 1st

Battalion Royal Ulster Rifles, from the air landing brigade of the

6th

Airborne Division, as part of the move towards Caen. They would

themselves then be leap frogged by the RUR. The order went out to

trot and Bill observed ‘we were being fired on from across the

canal but I did not realise it and some of the men started falling

down. I thought what’s the matter with them before appreciating

they had been shot.’

A while later as

they moved towards Longueval, Bill was wounded by a mortar bomb. It

fell in a small patch of the bocage countryside, where he and four

other soldiers were positioned. One was killed and a fragment of the

bomb sliced through the toe of Bill’s boot, injuring him badly in

the foot so that he had to be taken to the Regimental Aid Post.

An artificer

sergeant major in a jeep then arrived at the RAP and said:

‘Are you alright?

You know what’s happening?’ ‘No, no what?’ Bill replied. He

said ‘all walking wounded are going back to England. Can you walk?’

‘Never mind walking’ I said, ‘I can bloody well run!’ He got

me onto the jeep and some of the lads onto stretchers and we went up

to the Casualty Clearing Station which was in the old brick works. A

lad came up who had been hit in the face but they got him there

carefully.

Eventually Bill was

evacuated by a DUKW (an amphibious truck) which took him out to a

Landing Ship Tank for the voyage back to England. It became come

practice in Normandy that these comparatively large vessels would

land their cargo of troops and vehicles at the beachhead and then

taken on board casualties, some of whom even received treatment from

medical staff while at sea. Back in England Bill was operated on to

remove the mortar fragments from his foot. However, after a spell of

recuperation he returned to the 12th

Battalion while it was being deployed during the final stages of the

break out from Normandy. As Hilary Saunders explained this was a

relief for most paratroopers after the frustrations of over two

months of defensive warfare that they had experienced since D-Day.

In September 1944

the entire Division was pulled out of Normandy and returned to

Britain for a refit, respite or leave period, and training. By now

the popular Dakota transport aircraft had become more widely

available and was being deployed to drop parachute units. Bill was

now a combat veteran and received a promotion to corporal which

placed him in charge of a section.

Bill’s next

period of action came in the Ardennes during the winter of 1944-45,

in what has become termed the Battle of the Bulge. On 16th

December 1944 the Germans mounted a thrust for Antwerp, initially

taking the Allies by surprise. Panzer units strove to reach Stavelot,

where there was a large Allied supply depot, and further south the

Germans managed to create a gap in the Allied lines between St. Vith

and Bastogne. The US 1st

Army, under General Courtney Hodge was forced back along a 50 mile

front, but further north the enemy offensive was halted. By 19th

December the overall position had begun to stabilise for the Allies,

helped in part by the German’s shortage of supplies, particularly

petrol. Although the bulk of the fighting on the Allied side was

conducted by the Americans, several British units were deployed to

the Ardennes.

The 3rd

and 5th

Parachute Brigades were rushed to the Continent at short notice,

having conducted some strenuous training since September 1944, which

included exercises in urban warfare. They were to cover the River

Meuse and hold a defensive line between Dinant and Namur, before

eventually going over to the offensive in January 1945. In that

winter of 1944-45 Bill recalled being rushed to South Coast where his

unit boarded the Queen

Emma and

set off across the Channel, only to be chased back into port by

German E-Boats (equivalent to the Royal Navy’s Motor Torpedo

Boats). Eventually, they did manage to cross, and in freezing weather

endured a torrid journey by truck with little protection from the

elements. As Bill remarked ‘sometimes officers would take turns to

let a man sit in the cab of the truck in an effort to keep us warm.’

Initially there was

limited if any fighting for the 12th

Battalion, although the unit formed a succession of defensive

perimeters. Subsequently, the Battalion and the rest of 5th

Parachute Brigade endured a period of particularly grim fighting at

Bure. It was during this that Bill witnessed first-hand an inspiring

example of leadership that had a morale boosting effect on the men.

One of their senior officers in a plummy voice said to a fellow

officer with regard to artillery support: ‘Nigel I am not happy

about the situation. Could you please give them a stonking [soldier’s

term for an artillery barrage].’ As Bill put it hearing this and

the manner in which it was delivered ‘did us the world of good.’

After the Ardennes

12th

Parachute Battalion was deployed in Holland, notably conducting

awkward patrols along the Maas. Not only was the weather cold and wet

but mines posed a constant threat to infantry, particularly along the

river banks. The Battalion and rest of the 5th

Parachute Brigade performed well, and sometimes conducted company

sized sweeps. For the most part from Bill’s perspective as a

section leader, he remembered Holland during early 1945, as being

dominated by ‘a bit of shelling and a few snipers. Nothing we

couldn’t deal with.’

On one occasion a

particularly interesting time was had when they handed over to an

American unit that demanded to know where their tents were. The

paratroopers spent some time attempting to explain to the Americans

that British soldiers didn’t tend to have tents. As Bill recounted

the American troops demanded: ‘Where’s your pup tents?’ He

replied: ‘We sleep in the trench and it’s a three man trench so

that means only one man gets up and the others get two hours sleep.’

As they left the position the Americans were busy putting up their

tents, and Bill felt ‘you could imagine Jerry thinking what the

hell is going on over there?’

During February

1945 the 6th

Airborne Division returned to Britain and began preparing for its

role in Operation Varsity, the crossing of the Rhine. Based on

experience at Arnhem and elsewhere it was decided to transport all

the airborne troops involved in a single lift. They would also be

landing either by parachute or glider on top of their objective which

would dispense with the need for an approach march, during which the

enemy might have been able to hinder their progress. The airborne

assault would occur in daylight to aid navigation and as Bill noted

crucially they would be flying in with the ground forces already

having commenced their operations. Once landed the 6th

Airborne Division was to secure the northern flank of the 18th

US Corps.

A witness to the

drop talked of the roar of aircraft, sound of small arms fire, thumps

of flak or anti-aircraft fire and wave upon wave of parachutists. The

12th

Battalion had difficulty because its rendezvous was under heavy fire,

but the situation improved when a platoon under Lieutenant P.

Burkinshaw captured some German 88 mm guns that had been causing the

main problem.

Subsequently, the

12th

Battalion played a part in the advance to and fighting for Erle,

during which Bill was wounded for a second time.

Moving forward

because we were in the front line we sprayed them with bullets. The

Germans were running away from us and we got over the top and crossed

this trench. I was a section corporal by then and the officer had

been killed and my sergeant had taken over the platoon. I looked back

and nobody was getting up so I gave that well known word of command

‘Up on, Howay lads!’ Shortly afterwards we were point section as

there was no time to swap over. A small tank came up and we followed

behind it. The tank was hit, the officer in front of us had been

killed and his batman [military servant] badly wounded. Sargent

Kitchen said ‘Go back he has been hit.’ Then Lieutenant-Colonel

(later General) Darling launched a full scale counter attack and we

found we were in the middle of a Hitler Youth training camp.

During the

fighting at Erle Bill received a bullet wound to his leg and was

eventually evacuated to Bruge. The medical staff who treated him

considered it wisest to leave the bullet in with a view to removing

it after the war. For a few weeks Bill was posted to a convalescent

depot where he was given a job once the authorities discovered his

background in the grocery trade.

By VE-Day (8th

May 1945) he had returned to Britain, and at Lark Hill was surprised

to discover the stores were full of jungle green kit. Much to the

displeasure of his mother, Bill was among those airborne soldiers

posted to the Far East, at what proved to be the tail end of the war.

By now he had been promoted sergeant. The 5th

Parachute Brigade was to participate in Operation Zipper, the

proposed invasion of Malaya, and when the atomic bombs were dropped

and the surrender was signed with Japan it was in Singapore. Here

duties included looking after part of the notorious Changi Gaol. Most

of the Brigade was then sent to Java, as the Dutch East Indies (later

Indonesia), attempted to recover from the Japanese occupation during

the war and Indonesian separatists sought to exploit the situation.

However, Bill did

not go with them and was instead posted to India, still then part of

the British Empire. This was an awkward period for the 12th

Battalion as it absorbed new reinforcements who had to be brought up

to standard as rapidly as possible. Similarly, there were several

‘barrack room lawyers’ within the ranks who with the war finally

over saw no reason why they should have to remain in the army.

From India Bill was

sent to Palestine, where the 12th

Battalion was split up and he ended up with 4th

(Wessex) Battalion. In the late 1940s the British Army was expected

to keep the peace between Jews desperate for an independent state and

the local Arab population. As Bill put it ‘we were piggy in the

middle.’ Suppressing terrorism and maintaining law and order was a

different experience for soldiers like him, who had been used to

operations against the Axis Powers, and initially only joined the

army owing to the war.

During one riot

he was hit the face by a brick ‘I had my back to these Jewish

rioters. Suddenly there was a cry ‘‘watch it’’ and I saw the

brick and it split my eye completely open and I saw this little bloke

who did it run off. I cried ‘‘you bastard!’’ It was bleeding

like hell and opened up.’ The officer said ‘you were lucky. We

were expecting you to get stabbed in the back.’

After Palestine

Bill eventually returned to Britain during the harsh winter of 1947

and endured tough conditions at an old wartime camp, formerly used by

the US military. On account of his experience and holding the

necessary qualifications he was told that if he stayed on in the army

he would make sergeant major. However, Bill had seen enough by then

and did not feel he wanted to sign up for a further engagement with

the Colours.

On leaving the army

he went back to the Co-Op and went to work for an outlet in Byker. He

found First World War veterans who worked for the Co-Op had similarly

found it difficult initially in civilian life after returning from

the military, and like him did not always feel that their sacrifice

was fully recognised.

In the 1960’s

Bill left the Co-Op and was employed by the Tyneside based

engineering firm Parsons. For around 19-20 years he worked on

machinery as a hand winder, before taking early retirement in the

1980s. He was granted a small pension from the army and received

medical help, especially for his hearing, when he was referred to a

doctor who has also, been in the Parachute Regiment. Today he is

President of the West Jesmond Branch, Royal British Legion and

Tyneside Parachute Regimental Association. He has many interests and

particularly enjoys seeing his family, plus being active in a choir

with his friend and fellow Second World War veteran George Henderson,

who served in the Royal Navy. It was a privilege to meet Bill and

below are listed the materials used to construct this account of his

war/life experiences.

Sources

Interview with Bill

Ness by James Goulty, at his home in Byker, 26/1/15

Anon, By

Air into Battle the Official Account of the British Airborne

Divisions

(HMSO, 1945)

Anon, Home

Guard Manual 1941

(Reproduced by Tempus Publishing Ltd, 2006)

Gale, General Sir

Richard A

Call To Arms: An Autobiography

(Hutchinson, 1968)

Howarth, David Dawn

of D-Day

(Odhams Press Ltd, 1960)

Mackenzie, S. P. The

Home Guard: A Military and Political History

(Oxford University Press, 1996)

Parkinson, Roger

Encyclopaedia

of Modern War

(Granada Publishing Ltd, 1979)

Saunders, Hilary St. George The Red Beret (Odhams Press Ltd, 1958)

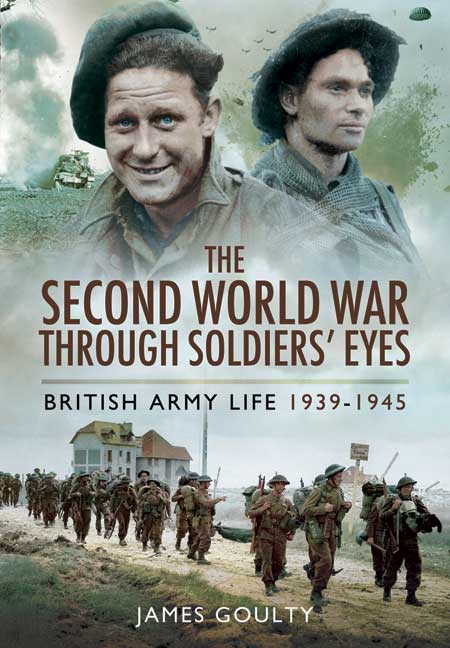

The Second World War Through Soldiers’ Eyes is available to order now from Pen and Sword.