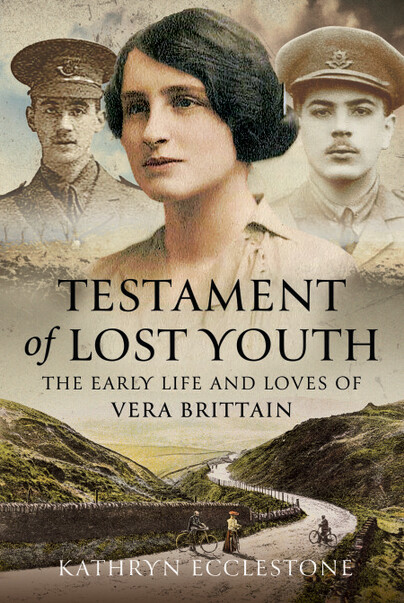

VERA BRITTAIN’S EARLY LIFE – TRUTH OR FICTION?

Guest post from Kathryn Ecclestone.

At the age of 25, Vera Brittain ended the First World War traumatised, utterly disillusioned and on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Alongside the horrors of nursing on the French Front, her fiancé Roland Leighton, adored brother Edward and two close friends had been killed. In her haunting First World War memoir, Testament of Youth, Vera said “Roland had taken with him all my future, Edward all my past. Only ambition held me to life”.

With incredible stoicism, Vera Brittain devoted the rest of her life to feminism and pacifism, producing 29 books (including five novels), a prolific output of journalism and being a renowned public speaker. Her most acclaimed work is Testament of Youth. Published in 1933, it catapulted her to celebrity status.

Vera died in 1970 at the age of 76. When the feminist publishing house Virago re-issued Testament of Youth in 1979, it went back to the top of the bestseller lists. An award-winning BBC dramatization in 1979, followed by a film in 2014 have brought new admirers to Vera Brittain.

My own admiration began in 2020 when I moved into her former home in the once-fashionable spa resort of Buxton in Derbyshire. Inspired by this unique sense of place, I gained access to Vera’s previously unpublished diary, letters and photographs. Discrepancies in tone and content between her memoir and unpublished diary suggested that Vera’s public account of her early life and its impact on her later success had been rather one-sided. My biography sets Vera’s lively voice against a backdrop of great social change and an Edwardian ‘estate resort’ controlled and owned by the powerful Devonshire family. Its more nuanced account of this period and of a young woman her mother described as “complicated and unusual”, highlights even more poignantly than Testament of Youth just how much of herself Vera lost in the First World War.

The morally serious, “mentally voracious”, ambitious, spirited protagonist of her memoir vies for space in Vera’s diary with an exuberant, often giddily enthusiastic, young woman who threw herself into everything she did, no matter how difficult or daunting. She loved clothes and being admired as much as the literature she devoured and veered between loneliness and a defiant sense of her own exceptionalism, moody prickliness and happiness, idealism and frivolity.

The reasons for Vera’s one-sided public portrayal are as complicated as she was. She noted in the preface to her 1930s diary that “today I feel only a remote family relationship with the girl who lived in Buxton and went to Oxford. I feel closer to my ten-year old daughter”. In Testament of Youth, she said it’s impossible to see “ourselves and our friends and lovers as we really were” because people resemble “strange ghosts made in their image, with whom they have no communication”.

Vera is far from alone in those feelings. Called on to narrate our past, we all, to a greater or lesser extent, subconsciously and consciously, reinterpret events, people, and our younger selves. It’s easy to erase unpleasant or unappealing aspects of our youthful character or to highlight those which complement how we see ourselves now. Our attempts to construct a sense of self and to understand the past make memory more an act of imagination than a matter of simple mental recuperation. More prosaically, Vera is not the only restless young person yearning for escape and adventure, hoping to meet more interesting people than our parents’ acquaintances, to carve out a meaningful life for oneself.

Beyond these universal tendencies, it’s impossible for a twenty-first century reader to understand how a brutal war which killed over 900, 000 British young men created an unbridgeable chasm between a lively, exuberant young woman full of hope and energy, and the psychologically and physically exhausted woman who had to rebuild her life.

When Vera began Testament of Youth in 1929, she was 36. Not only was she utterly changed emotionally and psychologically, but fourteen years had passed since she left Buxton, she had been married for four years, had one child, and was expecting a second. She was a renowned feminist journalist, member of the Labour party and a lecturer for the League of Nations.

Vera told friends “I’m writing the sort of book no one has written before”. A question in her 1914 university entrance examination had required her to explicate Thomas Carlyle’s view that ‘history is the biography of great men’. When an acquaintance at a London literary party heard Vera was writing her autobiography, he said ‘I wouldn’t have thought anything in your life was worth reading!’ Testament of Youth turned such notions upside down and redefined the genre of autobiography.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Vera did not, or could not, highlight sides of her pre-war persona that war had all but eradicated. And given the prejudice that would greet the autobiography of a relatively unknown woman, it’s understandable that she wanted to present a tidied-up, progressive and cosmopolitan version of her young self.

There’s also a literary reason for Vera’s one-sided portrayal. When she began Testament of Youth, she had published two moderately successful autobiographical novels and was working on another. In a burgeoning market for feminist fiction, key themes in Testament of Youth were already popular: an idealistic, intellectually ambitious protagonist fighting to escape ‘provincial young ladyhood’ for university; the oppression of being a ‘debutante’ in a provincial marriage market; cossetted by Edwardian “rich materialism and tranquil comfort” and untouched by events in the outside world before war destroys the lives of a gullible generation; rising above a philistine upbringing and the trauma of war to forge a career and achieve feminist womanhood in 1920s London.

Understanding Vera’s memoir as both truth and fiction enhances our appreciation of an extraordinary, intriguing young woman who went on to become one of the 20th century’s most significant political and literary figures.

Testament of Lost Youth is available to order here.