Margaret More Roper – The Female Tudor Scholar

Guest post from Aimee Fleming.

Devoted daughter, diligent scholar: This is normally the way that Margaret More Roper is remembered, if indeed she is remembered at all. Perhaps you may have seen A Man For All Seasons, in which Susannah York portrays a headstrong, somewhat rude Margaret putting the King in his academic place. She has had minor appearances in recent television shows such as The Tudors and Wolf Hall, but these fleeting glimpses do little to show us just how important and influential an individual Margaret really was.

Margaret was born in 1505 in London. She was the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas More, then an up-and-coming layer, and his young wife Joanna Colt. She had 3 siblings: 2 sisters and a brother, as well as several other children who came to live with the Mores and became adopted members of the family. At 16, Margaret married a young gentleman named William Roper, who had come to serve Sir Thomas as an apprentice while he studied to become a lawyer himself. Margaret and he grew up together in the house, and so when Margaret was deemed old enough, they were married. So far, so normal you may say, but Margaret and her family were far from normal.

From their earliest childhood, Sir Thomas gave Margaret and her siblings an unusually thorough education. This was not only from the standpoint of their class and status in society, which while later the family would climb the social ladder but in their early years the family was a normal middle class one, but also because of their gender. Margaret and her sisters were given the same opportunities as their brother and the other male members of their household, learning languages including ancient Greek and Latin, as well as mathematics, astronomy, biology and medicine. Under the guidance of Sir Thomas the children were given the most thorough education to be found outside of the royal courts, and, even more unusually, the girls were encouraged to pursue their own academic ambitions.

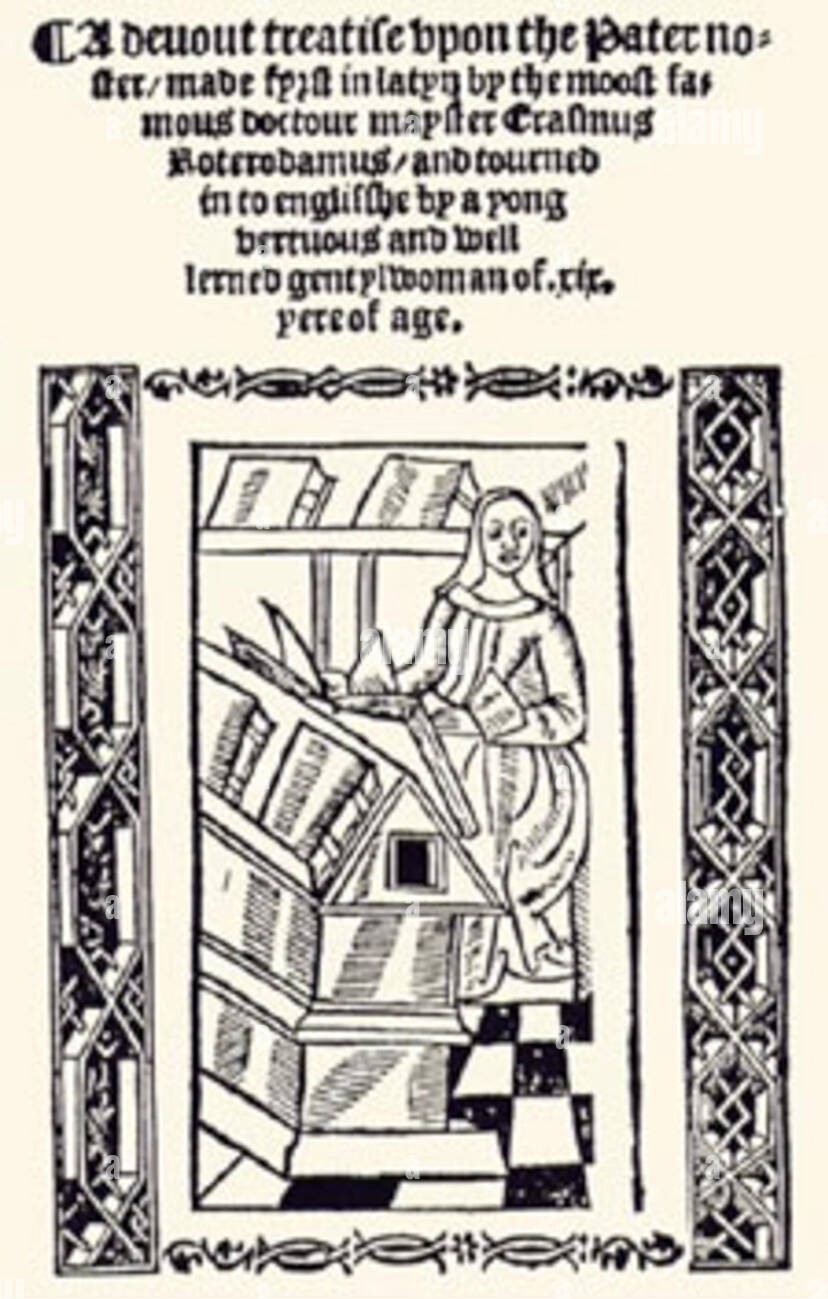

When Margaret was 19, she took on a project that would ensure that she left a legacy. She translated the ‘Precatio Dominica’, which she entitled ‘A Devout Treatise on the Paternoster’, a study of the Lord’s Prayer. Erasmus had written in Latin, and Margaret translated the whole document into English and then, through family connections, her translation was printed and distributed all over England. The aim of the work was the encourage people to read the bible and other scriptures for themselves, and to learn about God and his teachings directly from the source, which was a popular and fundamental part of humanist teachings.

Margaret’s role in the humanist movement was very much influenced by her father, and their relationship was a close one. He wrote to her when he was away on state business and would tell officials he met on his travels about her achievements as well as those of her siblings. This allowed Margaret and the rest of the More family to gain a reputation both at home and abroad.

One way we know that they were well known is through writings found very recently in a copy of the Qur’an in the Bodleian Library. The inscription, written into the margins, reads:

‘…whose name is callid Thomas More

knight lord chancellor of England the

to and twenty yere of king henry the eight and he had

thre daughters exelently lernid in the laten Greec and Hebrew

whose names were Margaret Bes and Cecile of whom in

special Margret Roper was alone the most noble of any that ever lived…’ 1

Margaret’s relationship with her father continued throughout her life, and all the way up until his death she was his loyal supporter and helped him when he was imprisoned prior to his execution. She negotiated for him to have better living conditions and visited him often, when they would walk and write together and discuss events happening at court.

Even after his death, her loyalty to her father as admirable. She collected all her father’s works; his papers, books, letters and anything that may have been special to him in life, hoping to preserve her father’s legacy for future generations. She even risked her own life to preserve the one part of her father’s body that survived the execution, his head, which was put on display on a traitor’s spike. She bribed the guard to retrieve the head instead of allowing it to fall into the River Thames, and she kept the head with her until her death, when it was buried with her.

After Margaret’s death as the young age of 39, her collection of her father’s work was distributed amongst family, but this collected works was more useful than simply being a collection of family heirlooms. After Margaret’s death her husband, William Roper, began to write the first biography of Sir Thomas More; this biography, entitles ‘A Man of Singular Virtue’, is still used to this day by historians and researchers as it gives not only a dearth of information about Sir Thomas himself, but about life in Tudor England and events at the court of Henry VIII too. In order to complete this biography William used the letters, papers and books that Margaret had kept. Had Margaret not worked so hard to preserve her father’s legacy, perhaps we would not have such a vivid knowledge of the Tudor era as we now enjoy.

Margaret is therefore a woman to whom we owe a lot; both as women and as historians. Without her work, we may not have anywhere near the amount of evidence or source material, or indeed have, as women, the opportunities for education and equality that Margaret and her sisters so adeptly proved that women were more than capable of accomplishing.

References

All of the information presented can be found in my book. Specific quotations and images are referenced below.

- Berthold, Cornelius, and Claudia Colini. ““The most noble of any that ever lived in this world”: an encrypted text praising Thomas More’s daughter Margaret, contained in a miniature Qurʾan at the Bodleian Libraries.” Moreana 60, no. 1 (2023): 95-113.

Recommended Reading

More information about Margaret, her life and work, can be found in my book, ‘The Female Tudor Scholar and Writer: The Life and Times of Margaret More Roper’. For more general information about the lives of Sir Thomas More and his family, I would recommend John Guy’s ‘A Daughter’s Love’.