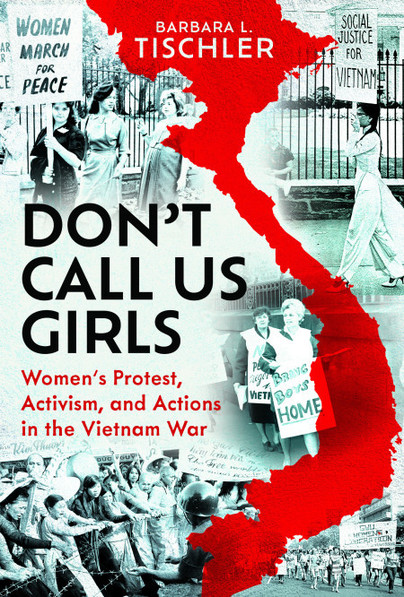

Don’t Call Us Girls

Guest post from Barbara L Tischler.

In celebration of Women’s History Month, this is a brief dive into the story of the origins of Second Wave Feminism in the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, Mexico, and Japan. It is not surprising that a movement dedicated to improving the lives of women emerged in advanced as well as rapidly-developing countries at about the same time in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Women’s movements emerged from the frustration imposed on women by patriarchy as well as dissatisfaction with women’s status in movements for social change such as the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and protests against the Vietnam War around the world.

In the late 1960s, women began to challenge long standing norms of polite behavior. In Great Britain for example, women could not enter a Wimpy sandwich bar after 11:00pm without a male escort. We can ask what horrors women would be subjected to late at night in a Wimpy bar.Women in many countries demanded the right to engage in civil society as equal citizens who could obtain credit by themselves, use their birth name after marriage, call themselves Ms, with no reference to their marital status, and participate in the workplace as equals.

Women protesters against nuclear proliferation and atomic testing in the 1950s and early 60s had generally been polite, even decorous, in their behavior. Early civil rights protesters followed this pattern: Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks refused to give up their seats on city buses in Montgomery, Alabama; the nine students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas were chosen as model citizens for their good behavior and excellent grades; and women like Septima Clark worked tirelessly for civil rights even after losing her teaching job because she refused to resign from the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). As the movement for equality gave way to calls for Black Power, women activists could be seen wearing black leather jackets, shouting angry slogans, and even carrying weapons. Unfortunately, even though women carried much of the burden of the Black Panther Party, they were often called Pantherettes.

Movements for greater say in university governance and frustration with government policy toward the United States brought students from many countries to the movement against America’s war in Vietnam. Thousands of Britons, led by actress Vanessa Regdrave, marched in the streets of London to deliver messages of protest to government authorities while students in Paris tore up the cobblestones of the city’s streets in their1968 protest that became a riot. Women attending a meeting of the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (Germany’s version of America’s Students for a Democratic Society) threw tomatoes at male movement leaders who refused to listen to their demands. Students who sought to modernize and democratize Mexican universities and Mexican society fought police in battles that led to death and injury.

Women’s protests against their second-class status revealed the intensity of the emerging movement. In 1968, women from the radical group Redstockings performed a funeral in Arlington National Cemetery for “true womanhood,” throwing accouterments of the traditional woman–girdles, curlers, and women’s magazines–into a coffin holding a mannequin. Protests against the Miss America Pageant in1968 in Atlantic City, New Jersey and the Miss World Competition in London in 1970 were equally spirited. The Freedom Trash Can on the Atlantic City Boardwalk was also a receptacle for items that evoked the traditional woman of the 1950s. Protesters called attention to what they considered a female meat market by symbolically crowning a sheep as Miss America. Reporters used the image of the bra-burning feminist as a way of describing the women who dared to flout convention. But in Atlantic City, the wooden boardwalk was susceptible to destruction from fire, so it was not set ablaze. The image of incendiary underwear proved to be more myth than reality, but it helped to sell papers. Protesters in London on 20 November 1970 picketed the Miss World Pageant, threw tomatoes and flour bombs, and shot the contestants with water pistols, calling attention to the objectification of women in beauty contests.

A few months earlier, on 26 August 1970, women throughout the United States had staged the Women’s Strike for Equality in which women were asked to withhold their labour in the household as a protest against opportunities for women and the absence of pay equity in the workplace. The date commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution that had awarded American women the right to vote. Marchers carried banners with slogans like “From Adam’s Rib to Women’s Lib” and “The Women of Vietnam Are Our Sisters.” The most pointed message of the day was a banner that declared “Don’t Iron While the Strike is Hot.”

As the National Organization for Women in the United States led the Strike for Women’s Equality, women in France affiliated with the Mouvement pour la Libération des Femmes selected the same date (26 August 1970) to launch a women’s protest in Paris. They laid a wreath at the Arc de Triomphe, the site of France’s tribute to unknown soldiers, in recognition of the person who was even more unknown than the soldier, his wife.

Women from many countries served in Vietnam as intelligence officers, clerks, administrators, and, most importantly, as nurses. In working conditions that can be described only as horrific, these brave women helped to save the lives of thousands of young men, many of whom had been drafted into service in a jungle war thousands of miles from home. Nurses returned from Vietnam with the same effects as male veterans–Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; health problems resulting from chemicals such as agent orange; and other mental and physical ailments. It took years of lobbying and protests for the Veterans Administration to include women in programs to assist veterans. In later decades, women served in combat roles in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the twenty-first century, women around the world face a backlash against the gains they have made in legal and institutional terms. Women now serve in law, medicine, government, business, and the arts in numbers that far outpace their presence in the era of Second Wave Feminism of the 1970s. But the trend toward eroding some of the benefits of the twentieth century and recent advocacy of a return to so-called traditional values (and the emergence of the “trad wife”) pose great challenges for women who call themselves feminists or who eschew the name but nevertheless speak out to demand greater equality. Women are still working for feminist causes–just don’t call them girls.

Don’t Call Us Girls is available to order here.