Author Guest Post: Lynn Hamilton

Mary Wade: From Felon to Freedom

For poor children living in 19th century London, every day was spooky, not just Halloween. London’s poorest families lived in ‘rookeries.’ These were heavily populated slums, subdivided to the point of insanity, with multiple families living in a single room. The dark alleys of these neighborhoods were so crowded, diseased, and dirty that no respectable people cared to enter. Even the police dropped their investigations at the outer edge of these communities..

The gutters were stagnant, and the undisposed garbage sat in piles. Groups of women dressed in rags and men with nothing to do created a breeding ground for assault, theft, and coercion. This vast no man’s land was a residential ghetto where even business cared not to venture. Vendors of stale vegetables and rag sellers were the only merchants. Yet, somehow, many of the residents were inebriated, drink being the only real anodyne to the worst poverty. The rookery was so crowded that, at night, the residents jockeyed to find enough space to recline. On a savage plus side, there was enough body heat to save them from freezing to death. There was no privacy anywhere. Every apartment was accessible by every other. The door frames were rotten, and the doors coming off their hinges.

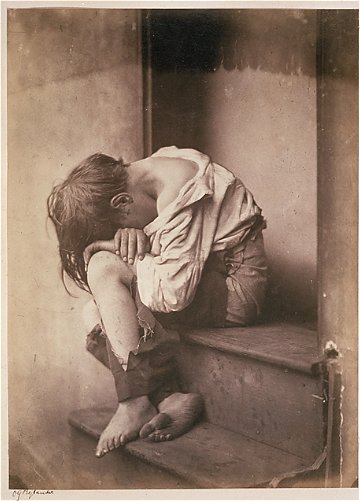

The rookeries were not specifically designed to breed child criminals, but the creation of such children was inevitable, given the poverty of the people who lived in these slums, combined with the lack of compulsory education. So many unintended children were conceived due to lack of privacy and the profound temptation to anaesthetise the pain of poverty with casual sex and alcohol. It is little wonder that the children born to rookeries were often brought up on charges of petty crime.

Within these rookeries, desperate parents cast their offspring on the street to find their own food. Parents of daughters often directly or indirectly sold their children into sex work. Boys would be sent into the city and told to come home with money or valuables. How the child got the valuables did not matter to such parents. Some children succeeded as beggars, though begging could also be prosecuted as a crime. Other children had to steal.

And the vast majority of ‘thefts’ were petty. The reason we know that so many children were criminals is that they were arrested for the smallest crimes–stealing a piece of fruit, a loaf of bread, a pin, a sheaf of paper, a handful of coals. There was almost nothing related to daily survival so humble that a street urchin did not want it. These street children would steal the clothes that were hanging on a line at the back of someone’s tenement. Or, in some cases, these young offenders took the clothes right off their victims, as they were standing on the street.

By today’s standards, it might seem outrageous that a child would be sent to prison for stealing a piece of fruit. But in 1851 and 1852, fifty-five children, under the age of fourteen, were sent to a correctional institute for fruit stealing and similar offences, in which the stolen item was worth less than sixpence. During the same period, another forty-eight children were sentenced for stealing items worth less than a shilling.

The punishments dispensed would be condemned by any civilised country today as human rights violations. At one point a judge condemned a ten year old boy to hanging for a petty theft. The judge’s reasoning was that, to let the boy off would be to encourage such crime. In 1801, a thirteen year old boy was hanged for unlawfully entering a home and stealing a spoon. In 1808, a girl of eleven and her eight year old sister were hanged. Hanging children would not be outlawed until the Children’s Act of 1908 made it illegal to execute someone under sixteen.

Mary Wade was a child of the London streets. There was so little interest in her welfare that, to this day, we don’t know whether she was twelve or fourteen when she became a convicted criminal. Mary mostly begged and swept the streets for pocket money. But one day she confronted another girl and stole her dress, cap, and small cape. She unloaded the dress at a pawnbroker, but was caught and arrested with the cape still in her possession. She was tried at the Old Bailey and sentenced to be hanged.

And there her story would have ended, but for a celebration taking place at the opposite end of English society. Early in 1789, King George III was enjoying one of his occasional respites from chronic mental illness, probably caused by porphyria. England breathed a communal sigh of relief so deep and grateful that all the women on death row, on which Mary sat, had their sentences commuted to transportation. Instead of being hanged from the neck until dead, Mary sailed aboard the Lady Juliana, the first convict ship to transport only women and children to Australia.

Many immigrants, especially those transported under criminal sentences, died on the horrible months-long ship ride. Others were summarily executed for petty crimes in their first months of penal colony life. Still others died from infection or disease in crowded ships and camps where contagion swept unopposed. In this hostile world, Mary grew and thrived. The Halloween of her childhood gave way to an Easter Sunday of prosperity and family love.

The Lady Juliana delivered Mary to Norfolk Island, and in that volcanic wasteland, she had three children. While living in a tent in Sydney, she had two more. She lived with Jonathan Brooker beginning in 1809, and eight years later, they were married. Both Brooker and Wade obtained certificates of freedom, and she had twenty-one more children. A bushfire in 1823 financially devastated the Brooker family, but they recovered, and by 1828 they owned over sixty acres of land. Mary lived to the ripe age of 84, long enough for her descendants to number three hundred. Tens of thousands of Australians carry her DNA, including former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. Mary Wade is, literally, the mother of her people.

Order your copy here.