Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

Saturday, 12 October 1940: The Battle Won

According to Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, Fighter Command’s Commander-in-Chief during the Battle of Britain, the contest began on 10 July 1940. This, his Lordship admitted in his Despatch published in the London Gazette, was an a arbitrarily chosen date. According to Dowding, the Battle ended on 31 October 1940. The great man was, however, writing during the Second World War, when German plans and machinations were unknown – unlike today, when historians have access to what were top secret papers from both sides. The question I would have for Lord Dowding, who died in 1970, is would he still have chosen those dates, if he knew what we do today?

The Battle of Britain, we are told, was fought to deny the Germans aerial superiority over southern England as a prelude to a seaborne invasion, not for any other reason. That being so, surely the Battle of Britain could only begin when enemy air operations were appended to an expressed intention to invade, and conclude when either the aggressor was decisively defeated or abandoned the enterprise?

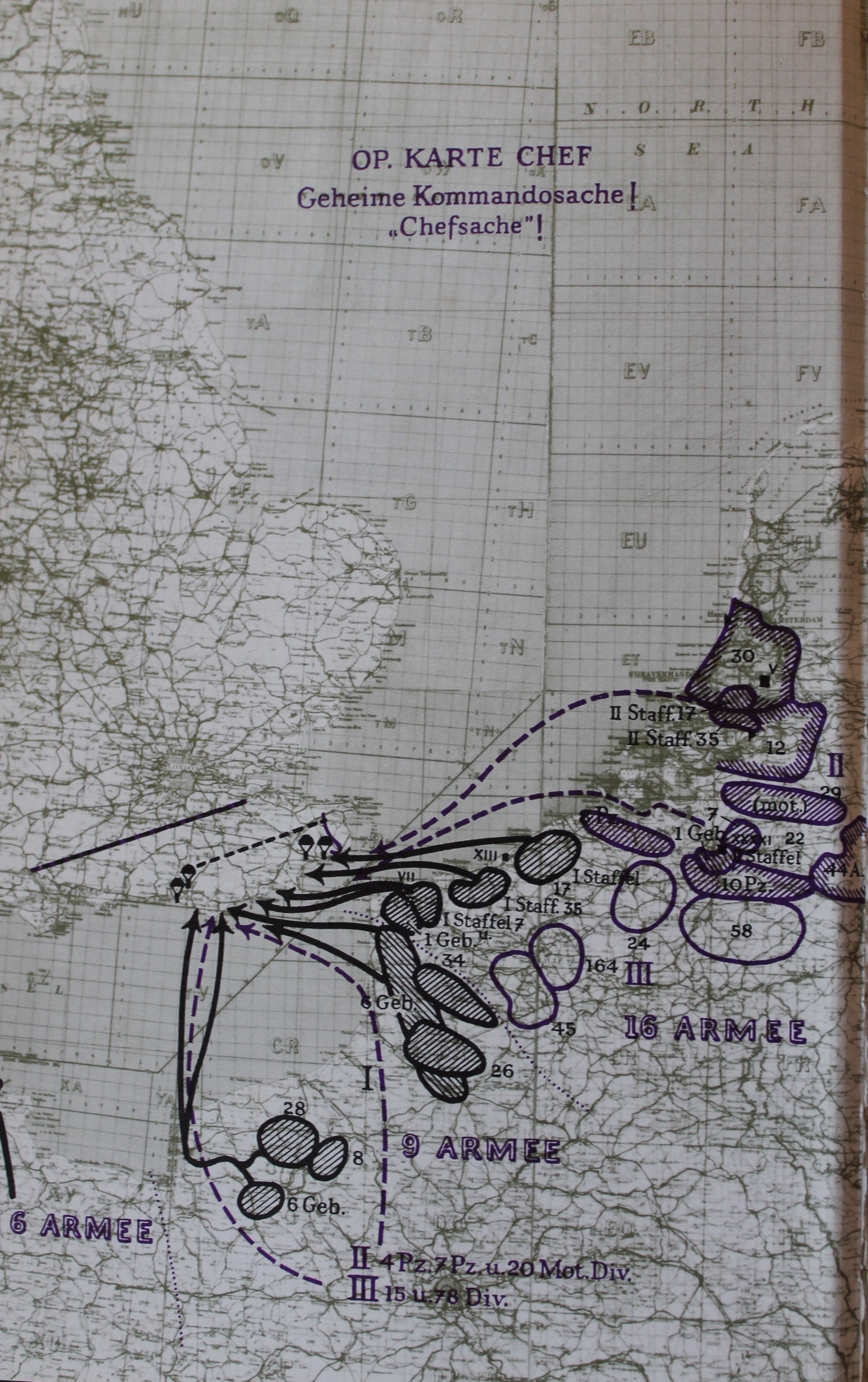

I would argue, therefore, that the Battle of Britain actually began on 2 July 1940, when the air fighting after the Fall of France resumed in earnest, over the Channel, and, crucially, because it was on that day the German high command, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) recorded Hitler’s intention to invade. Indeed, on that day, Hitler actually approved the invasion plan drawn up by the OKW’s Chief of Operations, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht being informed that landing operations would be considered if certain pre-requisites were met – the priority amongst which was aerial superiority. It is arguable, therefore, that the Battle of Britain began that day, because German air operations were now directly linked to achieving aerial superiority as the prelude to a seaborne invasion.

Lord Dowding, however, was unaware of these facts when composing his Dispatch, and chose 10 July 1940 as the start-date because that day saw the heaviest fighting so far. Some have since suggested that the Battle of Britain began on 16 July 1940, when Hitler issued his infamous Führer Directive No 16, outlining his intention to invade Britain in the event that favourable conditions were achieved, but the fact of the matter is that his decision had already been made, a fortnight previously.

Hitler’s attempts to force Britain to accept his surrender terms through Brinkmanship and ‘Air Fleet Diplomacy’ during June and July 1940, however, had wasted much time, and arguably the events of both 2 and 16 July 1940 were all part of his bluff, a misguided effort to frighten Britain into running up a white flag. All of this was building up to Hitler’s speech of 19 July 1940, his ‘Last Appeal to Reason’ – which was firmly rejected by Britain. Even then, the Führer dallied, wasting more time, before ordering an al-out aerial assault on Britain as a prelude to a seaborne invasion – the hazards of which Hitler was acutely aware. Nonetheless, Luftwaffe chief Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was sublimely confident, assuring Hitler that given four days of good weather, his Luftwaffe would destroy the RAF. Hitler believed him, and plans were made for the aerial offensive, the ‘Attack of the Eagles’, to be launched on 13 August 1940 – ‘Eagle Day’ – another date incorrectly suggested by some as the start-date.

‘Eagle Day’ – Adler Tag – ended up a damp squib owing to poor weather and miscommunication. The offensive was primarily aimed squarely at 11 Group airfields and was making progress when everything changed on 24 August 1940 – as the result of a navigation error, German bombs dropped on central London, such attacks being prohibited by Hitler and only allowed with his express permission. Cleverly, Churchill ordered an immediate retaliatory raid on Berlin, which went ahead on the night of 25 August 1940, shocking Germany and denting the Führer’s pride and prestige.

As Churchill expected, Hitler was baying for blood and hell-bent on revenge. So it was that the Luftwaffe turned away from hammering airfields at what was a critical time – the airfields were not knocked out, but had the battering continued, they could well have been. Instead, on 7 September 1940, the German assault on London began, reprieving 11 Group’s airfields and thereby enabling Air Vice-Marshal Park’s robust defence to continue. The attack on London, the Germans believed, Luftwaffe Intelligence having woefully underestimated RAF strength and misunderstood how Britain’s aerial defences were organized and controlled, would force Dowding to commit his last reserves to battle, which would be destroyed.

The date on which Hitler must decide whether Operation Seelöwe would sail or not was set for 15 September 1940. As things turned out, the Germans were met over London on that fateful day not by the last handful of Hurricanes and Spitfires but by several hundred of them – demoralizing Luftwaffe aircrews and making clear that the RAF was far from a beaten air force. Furthermore, this outcome convinced Hitler that, contrary to Göring’s boasts, the Luftwaffe was incapable of defeating the RAF in short order – and time, due to the changing season, was running out. Consequently, unable to delay any further, owing to moon and tide predictions, Hitler made his decision in the early hours of 17 September 1940: Operation Seelöwe postponed until further notice.

Could that, then, have been the end of the Battle of Britain?

The answer is no.

Although Seelöwe had been postponed, it had not been cancelled, and the aerial bombardment remained ongoing, arguably still aligned to an intention to invade in the event of favourable conditions being achieved. Indeed, the ever arrogant and overly optimistic Reichsmarschall genuinely believed that his Luftwaffe alone could still bring Britain to its knees.

By 30 September 1940, however, the Luftwaffe could no longer continue sustaining such heavy losses to its bomber force, all but the Ju 88 being withdrawn from the daylight battle. On 7 October 1940, the last major raid of the Battle of Britain was mounted by twenty heavily escorted Ju 88s of II/KG51, unsuccessfully targeting Westland Aircraft at Yeovil, after which that type also switched to night attacks. Bombing after dark was safer, because Britain’s nocturnal defences were inadequate, the trade-off being that it was less accurate, and hence the saturation bombing of large urban areas as opposed to specific military targets.

As October advanced, so did the autumnal weather, and with it was lost the unique and unexpected opportunity, presented by Hitler’s lightning Blitzkrieg of May and June 1940, to invade Britain. As early as 26 September 1940, Gross-admiral Erich Raeder, chief of the Kriegsmarine, had pressed Hitler to make a final decision about Seelöwe by 15 October 1940, because this high degree of readiness required to maintain the invasion fleet was negatively affecting naval strength elsewhere – not least the vital U-boat campaign.

Four days later, the OKW also wrote, requesting a decision by the same date, because the continued concentration of forces in the invasion ports had led to ongoing attacks by the RAF and ‘continual casualties’. Moreover, the Army’s winter training programme was now being impeded, and specialist troops, including engineers, could not be released back to their parent units in eastern Europe, where their presence was required.

On 12 October 1940, Hitler made his decision: there would be no invasion in 1940, preparations thereafter being ‘only a means of exerting political and military pressure on England’ – more Brinkmanship and bluff – and ‘Should a landing in England again be considered in the spring or early summer of 1941, the required degree of preparedness will be ordered at the right time. Until then the military basics of a later landing will further be improved’.

Seelöwe, which had been in a gradual decline since 17 September 1940, was finally off. Although Hitler still considered the war already won, the fact was that the Führer’s intentions in 1940 had been frustrated – and for the first time Germany had suffered its first major failure of the Second World War.

If we are to accept that the Battle of Britain was fought to deny Germany aerial superiority over southern England, and thereby prevent a seaborne invasion, then this epic aerial contest must surely have begun on 2 July 1940, for the reasons given, and ended on 12 October 1940, when Hitler finally abandoned Seelöwe and consigned this hazardous operation to the dustbin of history. Certainly, the Night Blitz and the daylight fighter sweeps and fighter-bomber raids continued, but these operations were no longer appended to an invasion plan.

At the time, of course, Hitler’s orders and intentions were unknown by Churchill’s War Cabinet, and to all intents and purposes Britain, bombarded by night and to an extent by day, remained an island under siege, the prospect of invasion, if no longer an immediate threat, still a haunting spectre. So, to the aircrews of both sides, the fighting continued …

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.