Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

Monday, 7 October 1940: The Last Raid

Having turned away from targeting 11 Group’s Sector Stations at a critical, if not decisive, moment, and instead bombed London round-the-clock, partly in retaliation for Bomber Command attacking Berlin and also in the mistaken belief that Fighter Command would commit its last reserves to defend the capital, when this latest stratagem failed, Reichsmarschall Göring changed tack once more.

Conducting the battle in this way literally flew in the face of the ‘Principles of War’, which advocated the concentration of effort on a specific front or target; ironically, the author, Von Clausewitz, was a Prussian. Unable to sustain such heavy losses by day, after the ill-fated raid on Westland Aircraft, which obliterated the picturesque Dorset town of Sherborne in error on 30 September 1940, the Heinkels and Dorniers were withdrawn to exclusively bomb Britain by night. So, on 1 October 1940, the Battle of Britain entered its final phase.

Although none of Germany’s bombers were long-range strategic types, the best available was the Junkers Ju 88: twin-engined, fast and heavily armed. Going forward, it was decided that only this bomber would operate over England by day, either in Gruppe strength (comprising three Staffeln, or squadrons), heavily escorted by fighters, or operating alone, in bad weather, using cloud cover to stealthily reach, attack and safely egress from their targets undetected. These raids were to be largely directed against the British aircraft industry and airfields, although the lone nuisance raids represented a growing investment in general damage and disruption.

By this time, one staffel of every Me 109 jagdgruppe had converted to the fighter-bomber role; although unpopular with the pilots, who felt that this unnecessarily reduced their already stretched resources, there was merit in this. Offensive fighter sweeps are only dangerous if defending fighters are scrambled to intercept – otherwise all the enemy does is waste time, fuel and effort. Including fighter-bombers in these formations, however, meant that no incursion could be ignored – and the Jagdbombers – ‘Jabos’ – were escorted by vast numbers of fighters, flying very high, ready to engage the intercepting RAF squadrons.

The first such Jabo raid occurred on 20 September 1940, and caught 11 Group out: assuming this to be a pure fighter sweep, defending squadrons were only scrambled when bombs, astonishingly, began falling on central London – and the German Jagdflieger, ready and waiting, gave Fighter Command a salutary lesson of just how lethal they could be in the right circumstances. This bombing, however, was inaccurate and random, in terms of what could be achieved when dropping a single SC250KG bomb from 20,000 feet with no bombsight or training. Nonetheless, this tactic of heavily escorted ‘Tip’n run’ raids would be a primary feature of the final month of battle.

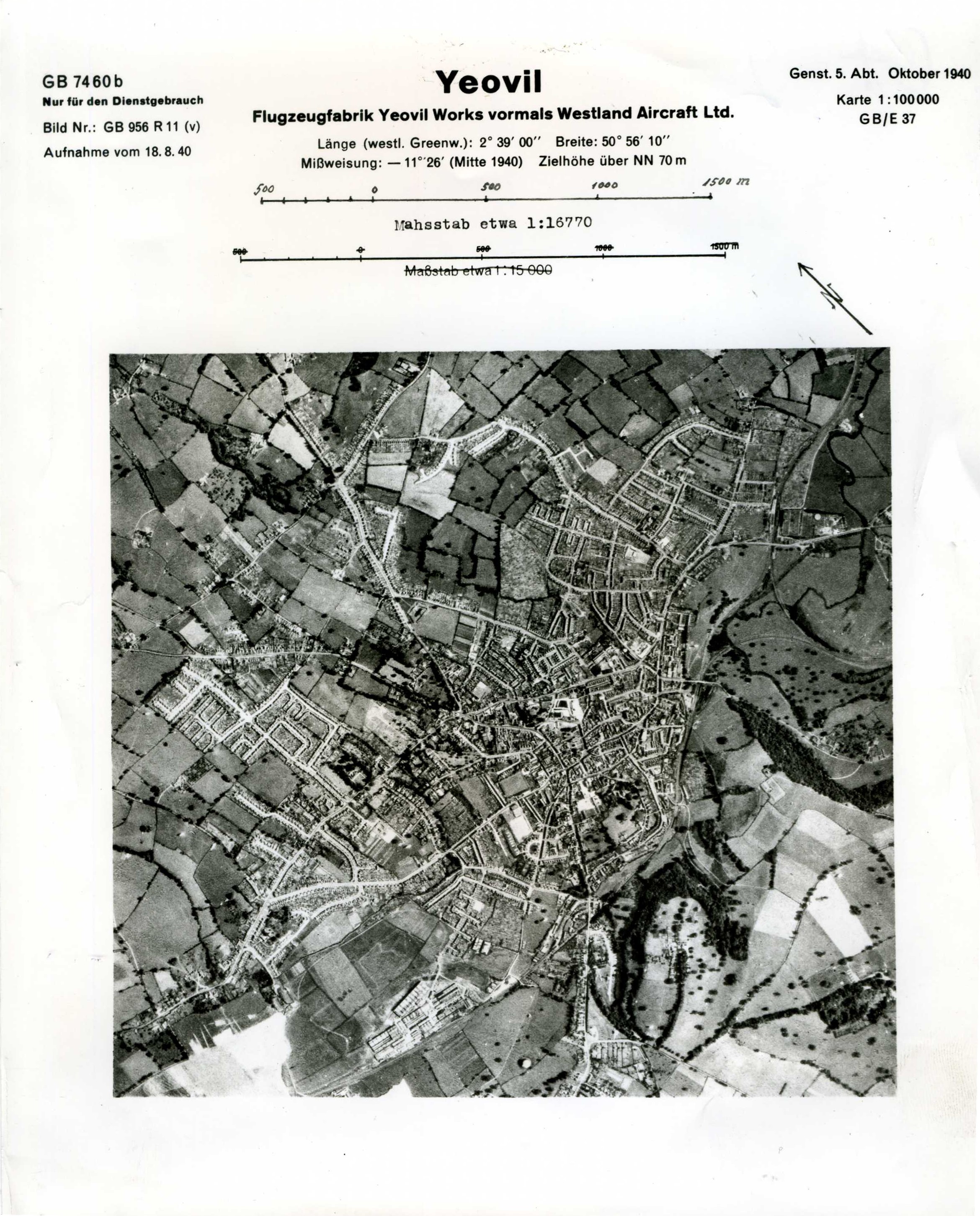

After KG55 had failed to hit Westland Aircraft on 30 September 1940, a second attempt was made on 7 October 1940, by twenty Ju 88s of II/KG51, escorted by thirty-nine Me 110s of the one-legged Oberstleutnant Joachim-Friedrich Huth’s ZG26, fifty-two Me 109s of Major Wolfgang Schellman’s JG2, and seven more of Oberst Günther Freiherr von Maltzahn’s JG53 – a formidable force indeed. Meanwhile, fighter sweeps and fighter-bomber raids would be ongoing over the 11 Group area, tying down defending squadrons. The raid on Yeovil, therefore, would be met by 10 Group’s Hurricanes and Spitfires, and Tangmere’s fighters.

In my The Final Curtain: 1 October 1940 – 31 October 1940, being the seventh of my eight-volume official history for The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust and National Memorial to The Few, published by Pen & Sword, the subsequent action is documented in detail, blow-by-blow, minute-by-minute, from a 360 perspective. Suffice it to say here that, yet again, Westland Aircraft escaped any serious damage – but Yeovil town centre was devastated. Fighter Command lost two Hurricanes destroyed and one damaged, three of their pilots wounded, and three Spitfires destroyed, two damaged, one pilot killed and three wounded, including poor Pilot Officer Akroyd who subsequently died of his wounds.

According to Hauptmann Genst’s after action report, I/ZG26 claimed a Spitfire and two Hurricanes, and II/ZG26 two Hurricanes; I/JG2 claimed three Spitfires and two Blenheims; II/JG2 four Hurricanes, and III/JG2 one Spitfire. Exaggerated though these claims were, there can be no doubting that the German fighter escorts did their job well, as II/KG51 only lost a single Ju 88. This, however, was at a cost: although the Me 109s returned to France unscathed, ZG26 lost seven Me 110s in what was also the types last significant showing during the Battle of Britain. In military terms, once more, the raid had achieved nothing of military value, just the destruction of another provincial town centre.

This raid by II/KG51 was, in fact, the last daylight attack by a formation of German bombers, all of which were now withdrawn to operate over Britain after dark – except those occasional harassing attacks by lone Ju 88s. The fighting by day continued, however, becoming a high-altitude contest between the fighters of both sides – more of which later …

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.