Author Guest Post: Bryan Lightbody

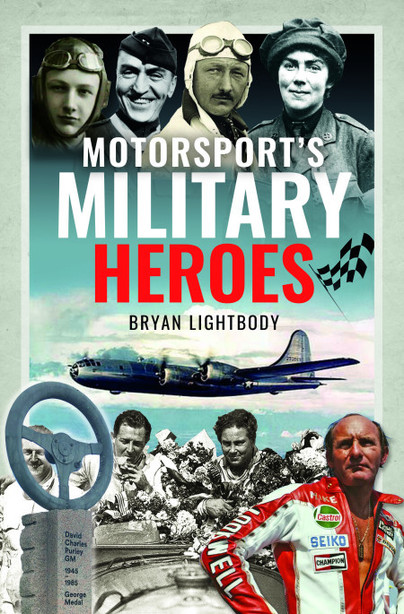

As previously highlighted, my enthusiasm for historic motorsport coupled with writing and battlefield guiding lead me to produce (what I hope will be) Volume one of ‘Motorsport’s Military Heroes’. It showcases some extraordinary individuals who braved all in war and on the racetrack. Male and female competitors, profiling individuals who raced from the 1920s up to the 1970s.

Moving on further, and examining more of the subjects on an abridged basis to give a flavor of the book, in this post we’ll continue with Raymond Baxter. He was best known as a TV presenter, but also a rally driver and most incredibly a respected and tenacious WW2 fighter pilot.

Raymond Frederic Baxter OBE (25th January 1922 – 15th September 2006) was born and raised in Ilford on the outskirts of East London. He revered his father, who was a teacher and was most likely responsible for Raymond’s lifelong passion for motorcars.

Like many boys of his age in this era he thrived on the creative mechanics of Meccano, a methylated spirits driven train set and days when he attended Croydon Airport with an uncle to watch the planes coming in.

He first attended Christchurch Road Elementary school before commencing secondary education at Ilford County High school. One of his school passions was singing, and in 1934 he even won a silver medal at the Barking Music Festival. His attendance at Ilford County High was dependent on passing the eleven plus exam, so a place there was prestigious. Raymond was a talented pupil with many interests, he boxed, he acted with aplomb in school productions and played the violin in the orchestra.

The day World War Two broke out he had cycled from home to the coast at Walton-on-the-Naze and was sailing when he and his best friend heard the sounding of an air raid warning at 11am on 3rd September 1939.

His world was further thrown into turmoil beyond this when he was caught smoking at school in a restricted area and the harsh disciplinarian headmaster expelled him in spite of pleas from other masters at the school. It crushed one of Raymond’s main dreams of trying to audition for RADA (the London Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts). He left school and drifted from working briefly at Hampton’s furniture store near Trafalgar Square, before taking a temporary position with the Metropolitan Water Board as he waited for the months to pass to be able to apply for the Royal Air Force as UT (under training) aircrew.

Entry into the training ranks of the RAF soon came as he reached seventeen years and nine months, first off billeted comfortably in St John’s Wood, London for initial Air Crew Receiving Centre, afterwards he was then transferred to Initial Training wing in Torquay. After a period of six weeks he passed out as a leading aircraftsman and was allocated equipment and clothing to commence flight training. Along with his fellow recruits he boarded a troop ship in Scotland and set sail under Royal Navy escort for Canada before further passage for flight training in Oklahoma. It was late winter/early spring of 1941, and the flight recruits were bitterly cold in the open cockpits of Fairchild, Vultee and North American aircraft.

Raymond achieved the distinction of being the first of his training course to fly solo after five days, having recorded total of six hours and fifty-five minutes. As well as the skill of flying the pilots were also taught navigation, night flying and blind-instrument flying.

During a period of leave Raymond took a Greyhound bus to New Orleans to see Louis Armstrong. Not only did he get to see him, he also met him and shook his hand. And they spoke.

‘I’ve travelled over four thousand miles for this,’ said Raymond.

‘Well, thank you,’ replied Satchmo, ‘and good luck.’

In May 1942 it was time for the journey home, a reverse of the journey taken to get to North America, and after a brief period of leave Raymond attended No 5 Advanced Flying Unit in Shropshire to start the final part of becoming a fighter pilot. On 18th July 1942 Raymond was strapped into a Hurricane for the very first time and knew that the experience of this aircraft and then the Spitfire was going to be very different to the machines he had flown so far.

Early in 1943 he volunteered for an overseas posting and Raymond found himself posted to No 93 Squadron in March and the North African theatre of war. No 93 Squadron was made up of Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Kenyans, Rhodesians and one American who had been in the volunteer American Eagle Squadron who fought in the Battle of Britain. Raymond flew with 93 for nine months during which time his logbook records active service in not only North Africa but in Malta, Sicily, Salerno, and Naples.

Raymond, or ‘Bax’ as he had become known, had complete confidence in the qualities of the Spitfire, including on one occasion when he had an under-carriage failure. When returning to Malta he could only get one wheel down, but then could not get the same one back up when considering emergency landing options. Flight control suggested he fly out to sea and bale out, but he didn’t want to lose an aircraft and felt that he’d seen too many bale-outs go wrong. He was confident that he could land on one wheel, and roll to a halt with minimal damage, which he did with only minor damage to the wing tip and propeller. Far more danger was yet to come.

Near the end of 1943 following operations moving onto the Italian mainland, Raymond went down with jaundice and by the end of the year he was back in the UK via RAF Lyneham. Six months followed ‘on rest’ flying as an instructor at Montford Bridge, Shropshire, which with mind to the fact he’d completed one and half operational Spitfire tours, been shot down, had malaria and jaundice, he wasn’t exactly taking a back seat.

For Raymond this posting was a great period, he recalled formation flying, low flying, dogfighting, night flying and navigation. And away from flying they escorted the ‘new chaps’ to the pub demonstrating how to behave, when to get drunk and when not to. It was also during his posting that he met his future wife Sylvia when he was part of a group invited to a nearby American OTU (Operational Training Unit). Raymond and three others pushed the swing doors open of the officer’s mess on the US base and after greeting their host, the base Colonel, Raymond saw ‘this beautiful, beautiful girl stood at the bar in a green evening dress who I asked to dance’.

It turned out Second Lieutenant Sylvia Kathryn Johnson was an American nurse at the 64th Field Hospital at Oulton Park.

Five weeks after D-Day Raymond was posted to mainland Europe with his CO a man called Max Sutherland, whom he describes as, ‘the most dangerous man I ever met, but I almost adored him’. Sutherland made ‘Bax’ the leader of ‘A’ flight of the 602 City of Glasgow Squadron.

Linked to the war on the V2, early in March 1945 Squadron Leader Max ‘Maxy’ Sutherland came upon a daring idea, he gathered his four most senior officers around him at drinks to share his concept. Max was a DFC recipient. For some time the men of 602 had been ‘flying their socks off’ in Operation Big Ben the dedicated anti V2 campaign. Raymond and the other pilots would see the rockets in their take off stage with their plumes of white smoke behind them as they accelerated skyward at phenomenal speed towards indiscriminate UK targets. In a later interview about his wartime career, Bax described once flying over a V-2 rocket site during a launch with his wingman firing on the missile. ‘I dread to think what would have happened if he’d hit the thing!’

Sutherland; ‘Outside The Hague is the former HQ building of Shell-Mex. It is now the centre of operations for both V1 and V2 attacks. I have worked out that the width of the building is equal to five Spitfires flying in close formation wing-tip to wing-tip.’ He paused and the said, ‘I reckon we can take it out’.

When the mission was launched, Sutherland led them in a perfectly judged dive down to one hundred feet with the target three hundred yards ahead in their sights. They each let loose with two 20mm cannons, 0.5-inch machine guns, one 500lb bomb and two 250lb delayed timer bombs. As they passed the target Raymond barely avoided a cockerel weathervane on a church spire, and Sutherland had his tail shot up badly. The five planes dispersed to draw fire and hopefully create confusion, but Sutherland in attempt to take a look back at the target took some more flak.

After the war had officially ended and having been posted to Egypt, in March 1946 Raymond walked into the studios of Armed Forces Broadcasting in Cairo and asked if they had any jobs. He was tested reading the NAAFI News and three weeks later he was posted to HQ MEDME Welfare (Middle East & Mediterranean). Later in 1946 Raymond Baxter was demobbed from the RAF and he returned to the UK.

Wanting to pursue a career in broadcasting, particularly with the BBC, Raymond took a job with the British Forces Network over the winter of 1946/47. This led to him reporting on the Berlin Airlift, hitching a ride at one point on one of the DC-3 (an aircraft he was familiar in flying).

Raymond Baxter joined the BBC in 1950. He provided radio commentary on the funerals of King George VI in 1952 and Winston Churchill in 1965, the former given from high up near the ceiling of Westminster Abbey. He also reported at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, reporting from Trafalgar Square.

From 1950 and for an unbroken thirty years Raymond attended the Farnborough Air Show as a BBC correspondent. Having an authoritative voice made Raymond Baxter suited to commentating on motoring and aviation events, this was in line with his natural talent as well as occupation in broadcasting, and passion for both motorsport and flying; a given with his flair and wartime experiences. Baxter is best known amongst a certain generation, for being the first presenter of the BBC Television science, innovation and technology programme ‘Tomorrow’s World’, with a tenure of 12 years from 1965 to 1977.

He was the BBC’s motoring correspondent from 1950 to 1966, including at least twenty Formula One races, the Le Mans 24-hour race, and the Monte Carlo Rally. His first BBC commentary for a motor sport event was from the Goodwood circuit in Sussex for the British Automobile Racing club Easter Meeting for 1950. Demonstrating a professional preparedness that was one of his hallmarks, two weeks before Raymond requested a list of ‘runners and riders’ for the event to memorise, and he contacted as many of the drivers as he could to establish himself. It cemented a place as the BBC’s principal motor racing commentator for the next 23 years.

On the subject of Formula One he made a cameo appearance in the 1966 John Frankenheimer classic movie ‘Grand Prix’ as a track side commentator/interviewer. By the paragraphs in his biography, ‘Tales of my Time’, on his experience with director/producer John Frankenheimer on set, he disliked his arrogant brashness, felt he hit the European racing scene like a bull in a china shop, and missed the opportunity to make the definitive motor racing movie. He also appeared in the films ‘The Fast lady’ and ‘The Green Helmet’.

For thirty-three years, he was the regular commentator at the Royal British Legion’s annual Festival of Remembrance at the Albert Hall, giving it up in 1996 after the death of his wife Sylvia, as in his own words, ‘I could not trust myself to cope with what was always an emotionally demanding experience.’ The Royal Tournament was another stalwart BBC TV event that he provided commentary for over several decades.

Raymond, through the motorsport connection, formed a strong friendship with twice Formula One world champion Graham Hill, and flying had brought them closer together including sharing a cockpit. When Hill was killed on 25th November 1975 it hit Raymond quite badly. Being connected to motor racing through the 1950s and 1960s sadly gave you a direct link to danger, tragedy and death. Not only did Raymond feel the tragedy of the loss of drivers in accidents he might not have witnessed, he did bear witness to what is probably motor sports most tragic accident in all elements; he saw how it happened, what happened and the enormous death toll. That was the Le Mans tragedy of 1955 when a Mercedes cartwheeled off the track into the main stand killing seventy-two and injuring more than one hundred people.

From 1949 Raymond Baxter competed in numerous Monte Carlo, Alpine, Tulip and RAC Rallies, winning his first ‘silverware’ in Hamburg. His first international event was the Lisbon Rally of 1950 at the invitation of a businessman ‘Goff’ Imhof. Raymond was his co-driver and went on to compete with him at Monte Carlo (Montes) and the Tulip Rallies in Holland. In 1960 he raced in the same team as Paddy Hopkirk, and eventually raced in the legendary BMC Mini Coopers team from 1964 again with Hopkirk and two stellar Finnish drivers. Raymond Baxter was without doubt an accomplished rally driver himself and competed in the Monte Carlo Rally a total of twelve times, six of them as a member of the BMC Works Team.

After a long career in television presenting, Raymond was invited to present the first ‘Raymond Baxter Award for Science Communication’ in July 2000. He was surprised to find that he was the first recipient. He was made an Honorary Freeman of the City of London in 1978 and awarded the OBE in 2003.

Raymond was a founder member of the Association of the Dunkirk Little Ships. He owned one of the small vessels that evacuated British troops from the beaches, purchasing L’Orage (formerly ‘Surrey’ during Operation Dynamo) in 1964. He became its Honorary Admiral from 1982. With his famed career and interest in flying he became Honorary Chairman of the Royal Aeronautical Society from 1991. He was on the Council of the Air League from 1980 to 1985.

Raymond Baxter died on 15th September 2006 at the age of 84 at the Royal Berkshire Hospital. Without doubt, Flight Lieutenant Raymond Baxter achieved much in his life, and is remembered as an avuncular radio and TV broadcaster, but during World War Two his tenacity and daring not only saw him twice mentioned in dispatches, but also immortalised in an aviation oil painting by Michael Turner, ‘Spitfire Special Delivery’. The Raid on the Shell-Mex building most certainly was.

Order your copy of Motorsport’s Military Heroes here.