Author Guest Post: Samuel de Korte

27 and 28 January 1944: The days when the Tuskegee Airmen showed the world they could fly and fight as well as white pilots.

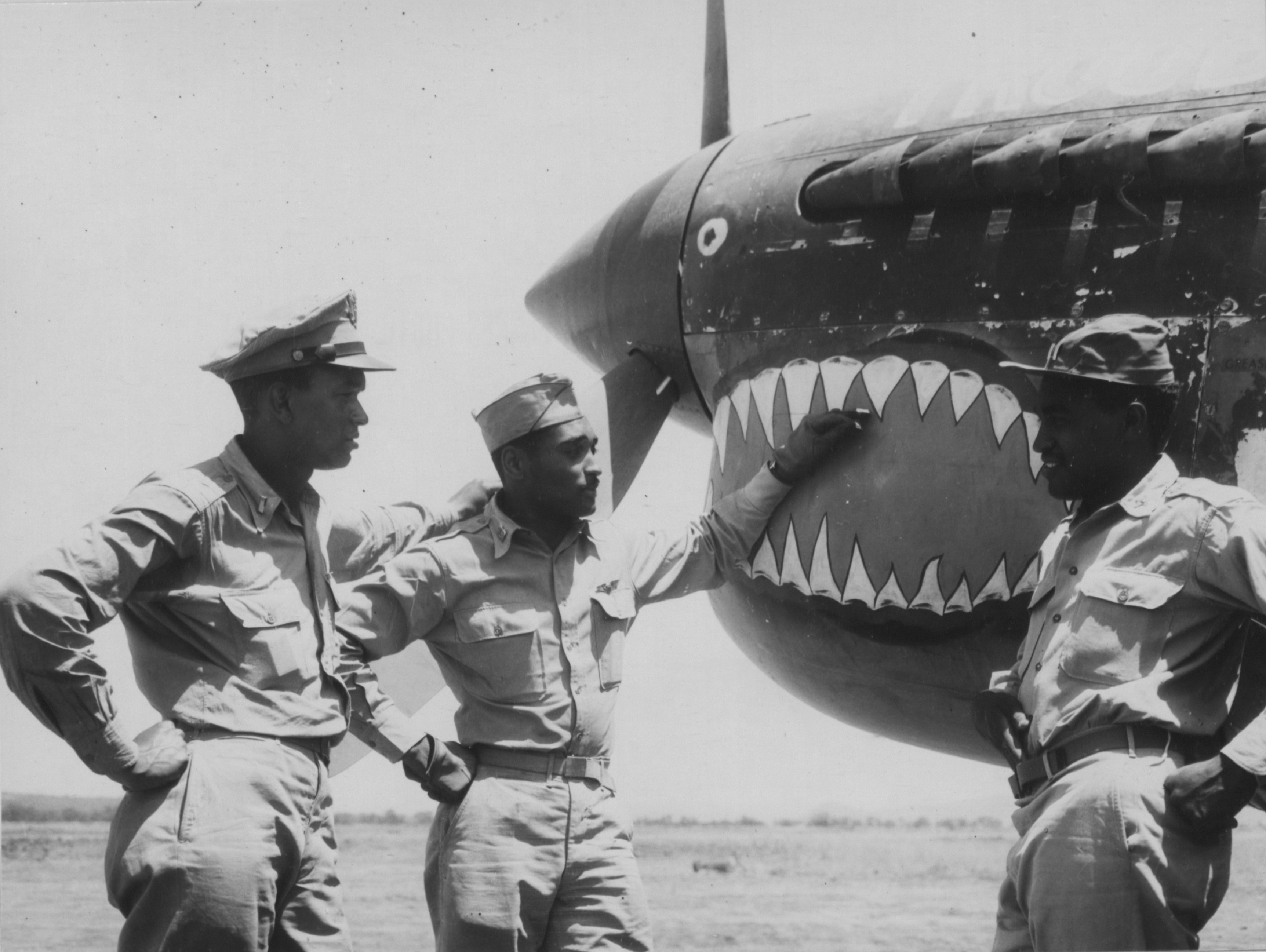

Before the Second World War, American society was segregated. It meant that there were dedicated train cars, dedicated schools, and dedicated restaurants for Black and white Americans. This extended to the armed forces, where there were dedicated units in which Black Americans were allowed to serve, such as the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiment or the 24th and 25th Infantry Regiment. However, in the Army Air Forces, there were initially no units for Black Americans. When Benjamin O. Davis Jr. neared graduation from West Point, where he was trained to become an army officer, he applied for the Army Air Forces and was rejected. There were simply no Black outfits in which he could serve.

This changed on the eve of the US entry into the Second World War. When the Army Air Forces finally relented under pressure, they established a unit on 22 March 1941: the 99th Fighter Squadron. However, the 99th was judged unfairly after entering combat and it was soon recommended that this unit would serve in a non-combat area. Due to this damning report, people questioned whether Black pilots could fly and fight as well as white pilots. This changed on 27 and 28 January 1944, when the 99th Fighter Squadron shot down twelve German airplanes in just two days.

27 January

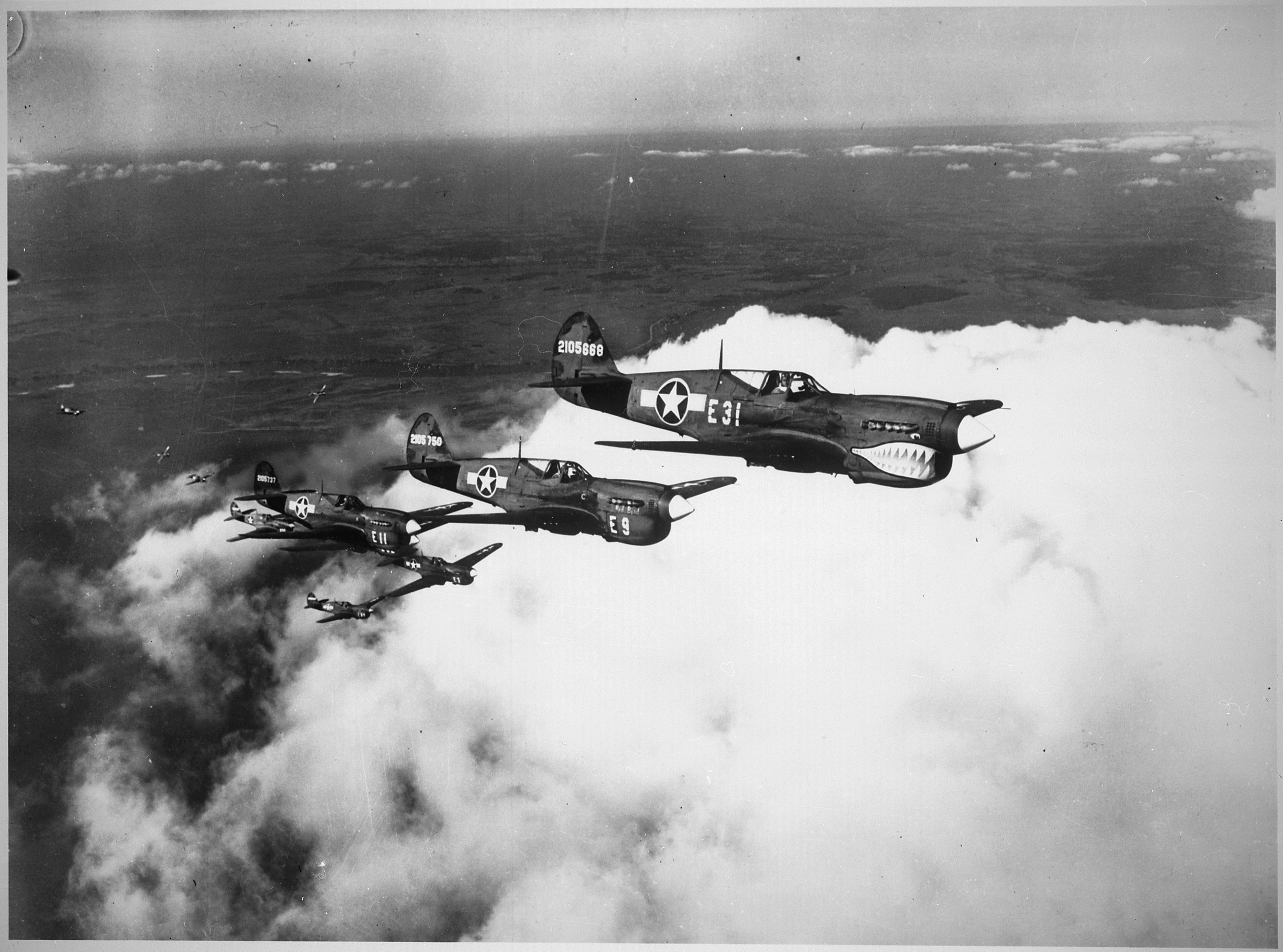

In the skies over Anzio, the 99th Fighter Squadron proved all their doubters wrong. After the Allies had landed on the beaches, the Germans tried to push them back into the sea. When arriving over the beach, the 99th saw several German aircraft divebombing targets below. The American pilots immediately dove into their enemy. They attacked ferociously and during the swirling melee, they shot down several German aircraft as the enemy tried to escape.

Later that day, during another patrol, the Germans once more attacked the Anzio beachhead, while the 99th Fighter Squadron was flying cover for the ground forces. They shot down three more enemy aircraft. As Lieutenant Howard Baugh commented on the battle of that day: “I saw 12 or more Focke-Wulf 190s cut away from our ships and hit the deck. I was flying about 5,000 feet and went down firing. I gave three or four bursts of fire, then saw one plane skid along the tree tops, throwing clouds of dust as it hit the ground.” However, the victory did not come without a cost. The pilot Sam Bruce perished after jumping out of his damaged plane. His parachute failed to open. He never got to meet his daughter, who was born one month after his death.

28 January

The next day, the 99th Fighter Squadron was flying cover over the Anzio beaches. The pilots had been invigorated by the successes of the previous day. Luckily for the pilots, this day, they had another chance to prove their worth, when the Luftwaffe made another attack at the beachhead. However, the 99th dove on the enemy as soon as they were within range. The enemy tried to turn away, but not before four airplanes were shot down. Captain Charles Hall shot down a Me-109, which burst into flames and crashed into the ground, while later he shot down a Focke-Wulf 190 with several short bursts. Lieutenant Smith hit a Focke-Wulf 190 from the side, which burst into flames and crashed. Lieutenant Robert Deitz shot down a Focke-Wulf 190 and the German pilot bailed out. The 99th Fighter Squadron suffered no losses that day.

The effects of that day

These two days changed the perception of the 99th Fighter Squadron almost immediately. The squadron had tangled with the Germans and managed to win. As described by Benjamin O. Davis: “We immediately received news of the 99th’s aerial victories over the Anzio beachhead on 27 and 28 January, just days before our landing. This came as a tremendous shot in the arm. The glamour of a quick succession of aerial victories immediately produced a wave of recognition for the 99th and other black airmen in the theater. No number of bombs expertly placed on ground targets or in support of ground troops could have produced comparable acclaim.” General John Cannon, who had previously endorsed a negative report about the 99th Fighter Squadron, flew over to the squadron and congratulated the men. “Keep shooting,” he said as he left. Praise from General Arnold, Chief of Air Corps, included: “The results of the 99th during the past two weeks, particularly since the Nettuno landing, are very commendable. My best wishes for their continued success.”

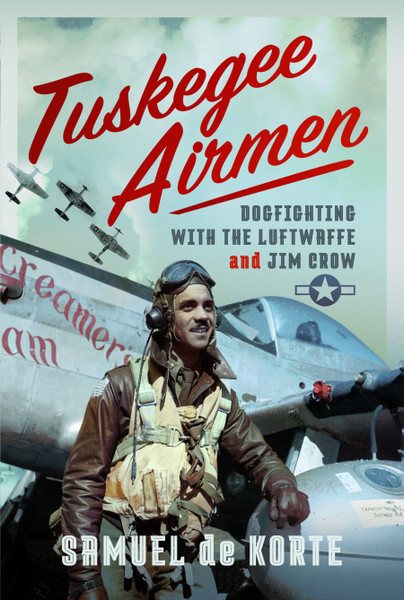

In two days, they had shot down twelve enemy aircraft, got three probables, and damaged four more. The Tuskegee Airmen had justly demonstrated that they could fly and fight as well as white pilots. The 99th Fighter Squadron, as well as the 332nd Fighter Group, continued to serve valiantly during the Second World War. If you want to learn more about the Tuskegee Airmen and their service during the Second World War, check out Samuel de Korte’s Tuskegee Airmen: Dogfighting with the Luftwaffe and Jim Crow.

Order your copy of Tuskegee Airmen here.