Author Guest Post: Dilip Sarkar MBE

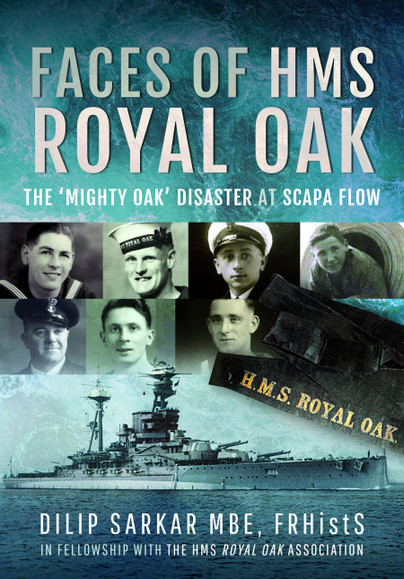

Faces of HMS Royal Oak: The “Mighty Oak” Disaster at Scapa Flow

When I was eleven years old I used to take the weekly Orbis History of the Second World War magazine, and in an early issue read for the first time about the sinking of HMS Royal Oak by U-47. Little did I know then what a journey I would go on in adult life connected with this tragedy.

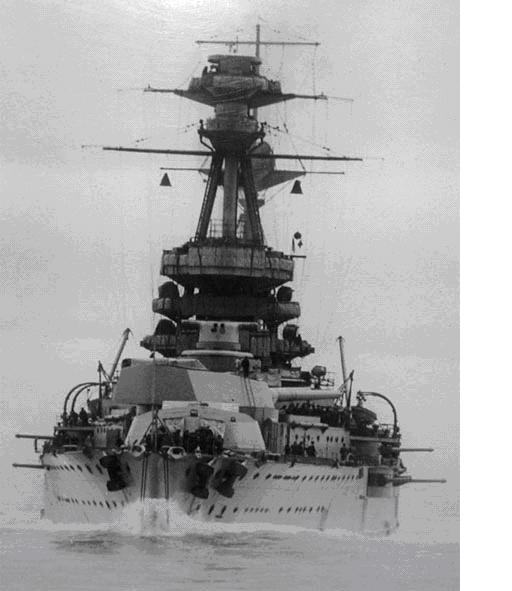

It is sad but fair to say the Second World War began badly for Britain’s mighty Royal Navy. On 17 September 1939, a demoralising loss was suffered when the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous – a valuable asset – was sunk by U-29 with the loss of 518 sailors. The First Sea Lord, one Winston Churchill, had ordered aggressive action against German submarines, the problem being that at first these patrols included slow capital ships – a mistake fully exploited by U-29. As the Courageous went down, just a fortnight into the Second World War, it was clear that the U-boat was as great a menace now as it had been during the Great War. Worse followed.

The British Home Fleet’s main northern base in 1939 was at Orkney’s famous Scapa Flow anchorage – a name hated in Nazi Germany. It was there that after the Armistice in 1918, the German High Seas Fleet was interred – until Midsummer Day 1919 when the German commander, Admiral von Reuter, scuttled his once proud Fleet. Moreover, in the wake of the Versailles Peace Treaty that year, Germany’s armed forces, amongst other things, were massively reduced, not least the navy, which was prohibited from having submarines. After Hitler came to power in 1933, though, the German Wehrmacht increasingly re-armed, at first in secret, as one by one the Führer renounced Versailles clauses – and was eventually sufficiently confident to announce that Germany possessed 129 U-boats with a combined tonnage equal to the Royal Navy’s submarine fleet. By 1939, a former First World War submarine commander, Karl Dönitz, was Kommodore of the 1st U-Boat Flotilla – and determined to avenge the humiliation of the High Seas Fleet. On 28 October 1918, however, UB-116 had attempted to penetrate Scapa’s defences but had been detected and destroyed by mines and depth charges. Indeed, although, in truth, requiring updating in 1939, the British defences were not inconsequential, booms and blockships sealing off entrances – but there was one place, a tight route between blockships in Kirk Sound, that a U-Boat might successfully negotiate. Dönitz, determined to get a U-Boat into the anchorage to wreak havoc on the Home Fleet, concluded that a daring and skilled commander might just get his boat through that gap at night, at slack water (when incoming and outgoing tides meet). This, he knew, was the ‘boldest of bold enterprises’, and the man he chose for this audacious sortie was Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien of U-47.

On 8 October 1939, Prien and U-47 cast off from Kiel, heading for Scapa Flow. On the same day, the German surface fleet made a sortie up the Norwegian coast to divert attention from the pocket battleships Graf Spee and Deutschland, which had also weighed anchor and bound for the South Atlantic. An RAF Coastal Command Hudson, however, spotted the main German fleet, the Admiralty suspecting that the intention was to breakout into the Atlantic. This could not be permitted, and so both the Humber Force, sailing from Rosyth, and the Home Fleet at Scapa, went to sea and gave chase. The operation was unsuccessful for all involved, as the Luftwaffe failed to locate and attack the main body of the Home Fleet, U-Boats made no contact whatsoever, and the Germans returned to Kiel without having been engaged. The incident, though, was significant for two reasons: firstly, owing to Luftwaffe air activity, the Home Fleet was dispersed, only HMS Royal Oak, an old battleship, HMS Repulse (a battle cruiser), HMS Furious (an obsolete aircraft carrier), and the cruisers HMS Newcastle and Aurora returned to Scapa Flow – thereby robbing Prien of the potential for a decisive blow against the Home Fleet. The North Sea, sortie, however, had shown that Royal Oak was too slow for such operations with more modern ships, so it was decided that the venerable old warrior, which had fought at Jutland, would take up station in the anchorage’s north-east corner, its anti-aircraft guns thereby bolstering the aerial defences of Kirkwall and the Netherburton radar station. A previous Luftwaffe reconnaissance sortie had reported sixty-three ships at Scapa Flow – and these both Prien and Dönitz expected U-47 to find.

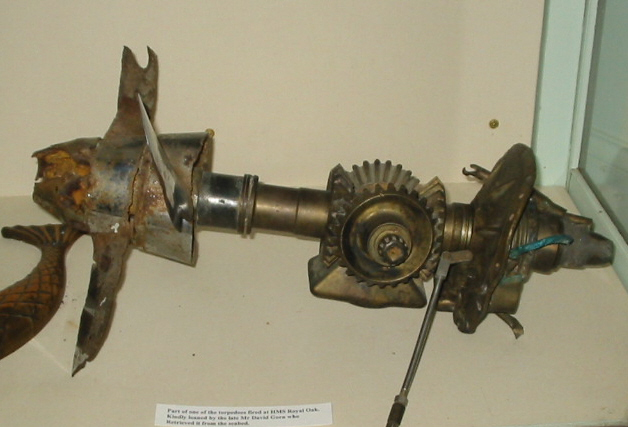

On the night of 13/14 October 1939, U-47 achieved that the Royal Navy believed to be impossible and entered Scapa Flow. There, Prien fired three torpedoes at HMS Royal Oak, one of which found its mark. The resulting explosion, so safe did the crew feel at anchor, caused little alarm, it being suspected that some kind of combustion in the paint store was responsible. Undetected, Prien fired another three ‘Tin Fish’ – and all hit the already stricken battleship. A magazine went up in flames, causing massive damage. It was a warm night and the crew, asleep in hammocks below deck, had left many portholes open – allowing water to rush in as their ship rolled over and sank. Within thirteen minutes, Royal Oak was at the bottom of the Flow – taking 835 of the ship’s company with her – many of whom were teenage ‘Boy’ sailors. On the surface, there was chaos: survivors floundered around in thick black oil whilst John Gatt, skipper of the drifter Daisy II, and his crew laboured to rescue as many as possible. For some, although only a mile offshore, the cold water and trauma was just too much, as survivor Boy 1st Class Arthur Smith remembered: ‘As I was swimming alone I heard splashing and came across another lad… we swam in silence until he suddenly said “Oh bollocks to this” and just disappeared under the water. I think that scared me more than anything else, to think that a young lad of 17 could just give up the ghost with no fuss or commotion. Poor lad just reached the end of his tether’. Over 300 survived, in fact – although there was confusion as to what had happened for time, it being thought impossible that an enemy vessel could have been responsible. Then, a local commercial diver, Sandy Robertson, was sent for, and in the cold light of day confirmed the unthinkable when he salvaged the remains of a torpedo.

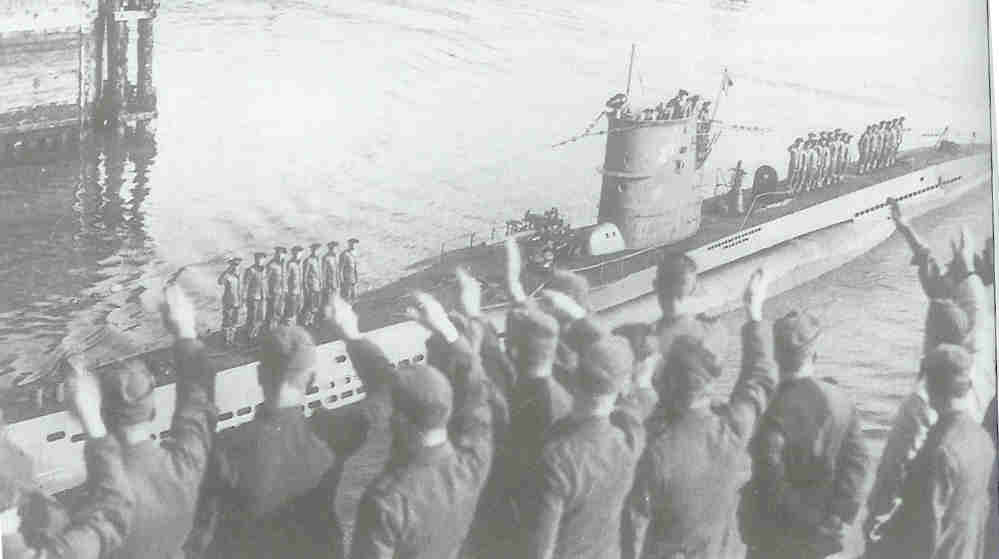

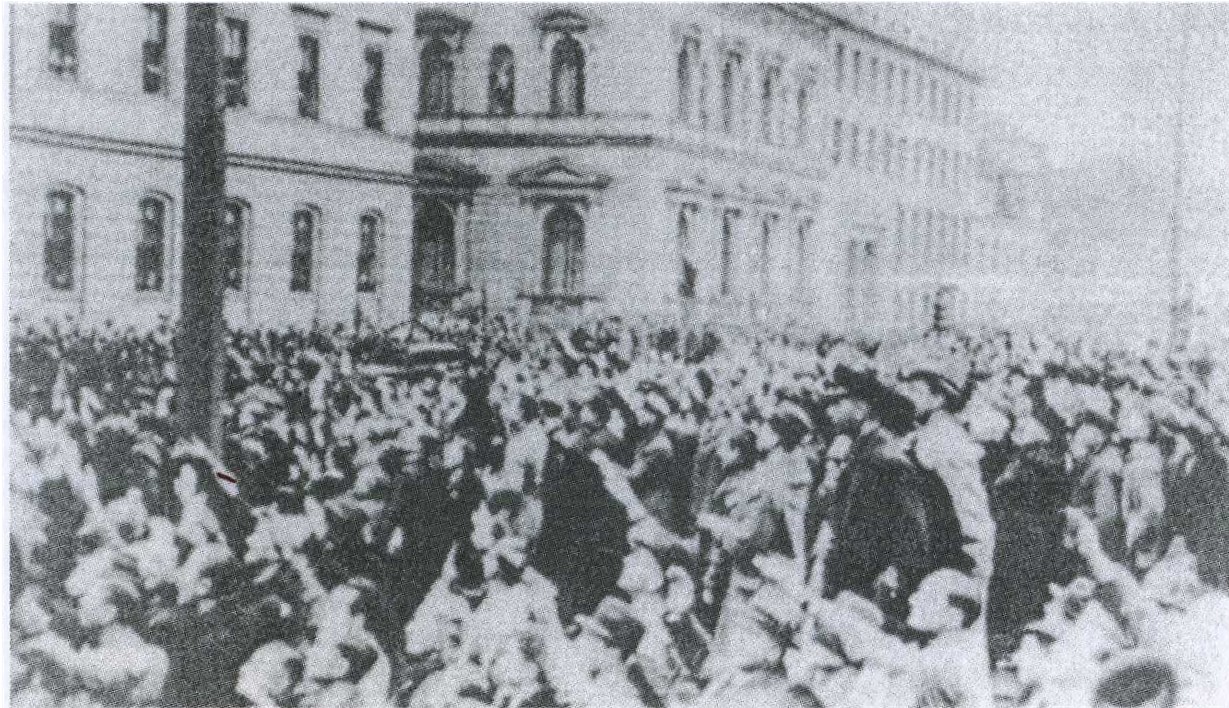

Meanwhile, Prien slipped away unnoticed, U-47 returning home to a heroes’ welcome. In truth, the raid was far from as successful militarily as Dönitz intended, but the tragedy was a massive blow to British morale and national pride – whilst in Germany the triumphal celebrations were bordering on hysterical, Prien being decorated with the Knight’s Cross by Hitler himself, who insisted on dining with U-47’s crew in Berlin. Needless to say, the Nazi propaganda machine trumpeted a wildly exaggerated account of the action far and wide. Exaggerated though it was, Prien’s sortie was, Churchill considered, ‘a remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring’ – and that no-one could deny.

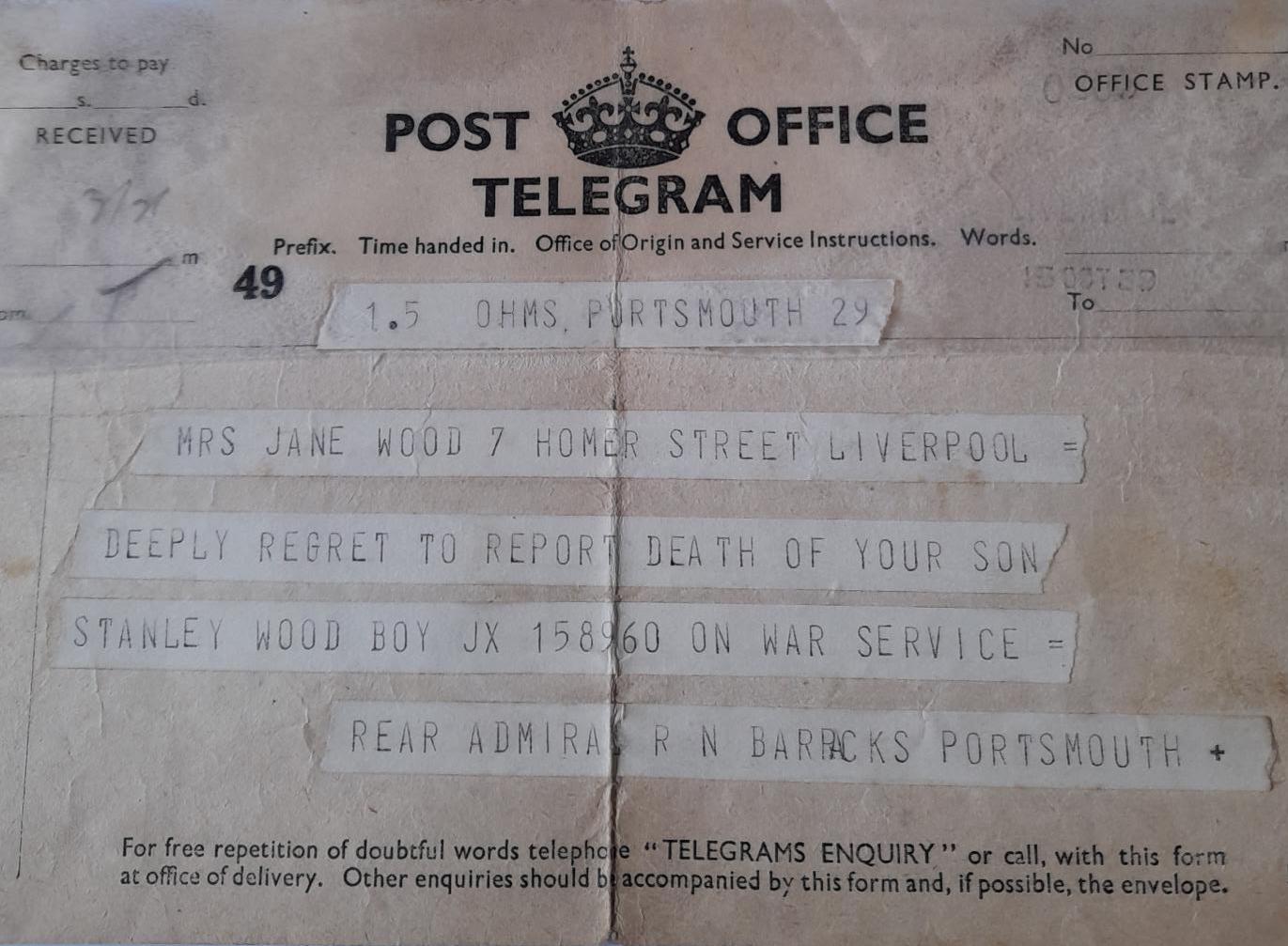

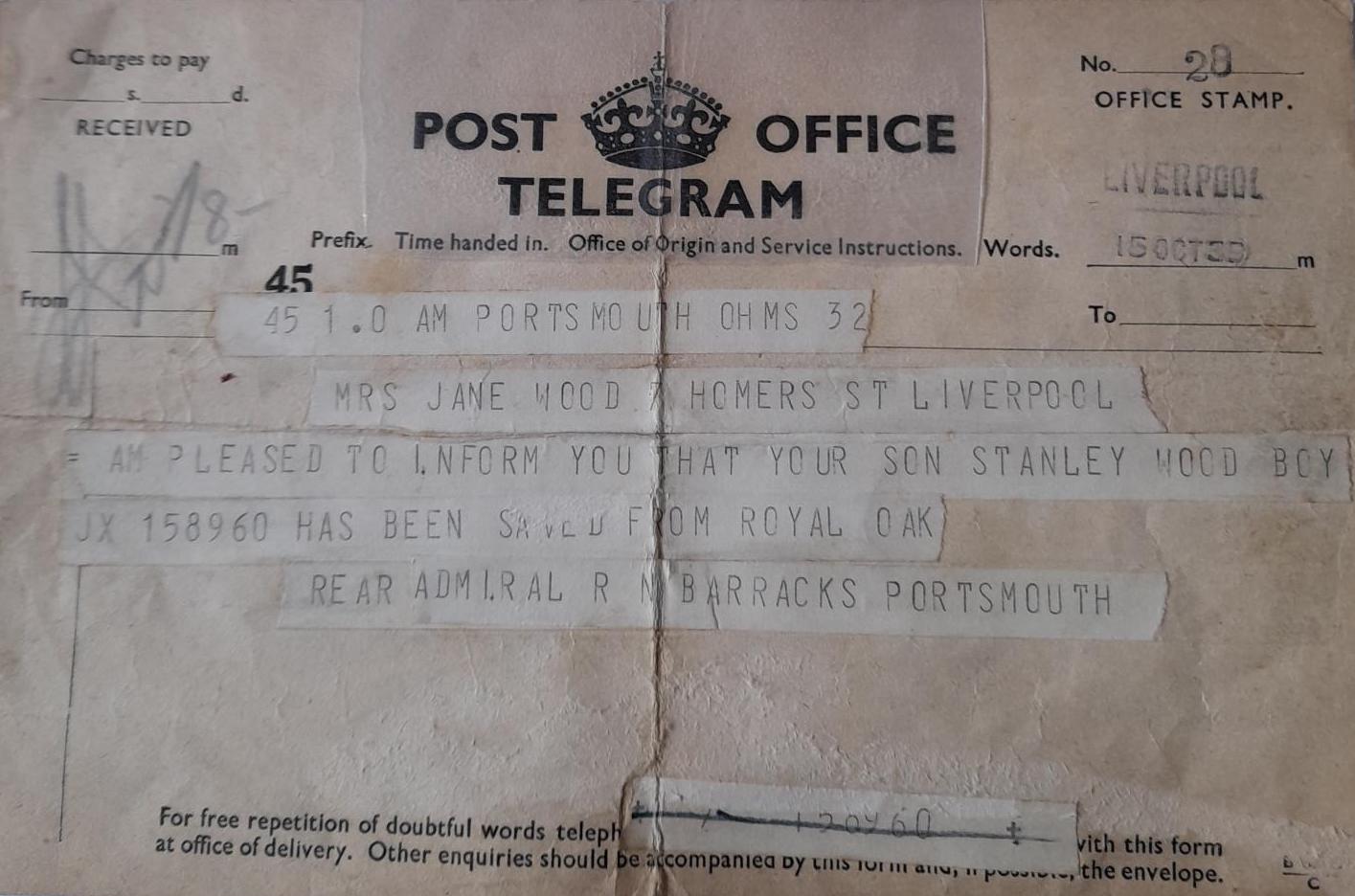

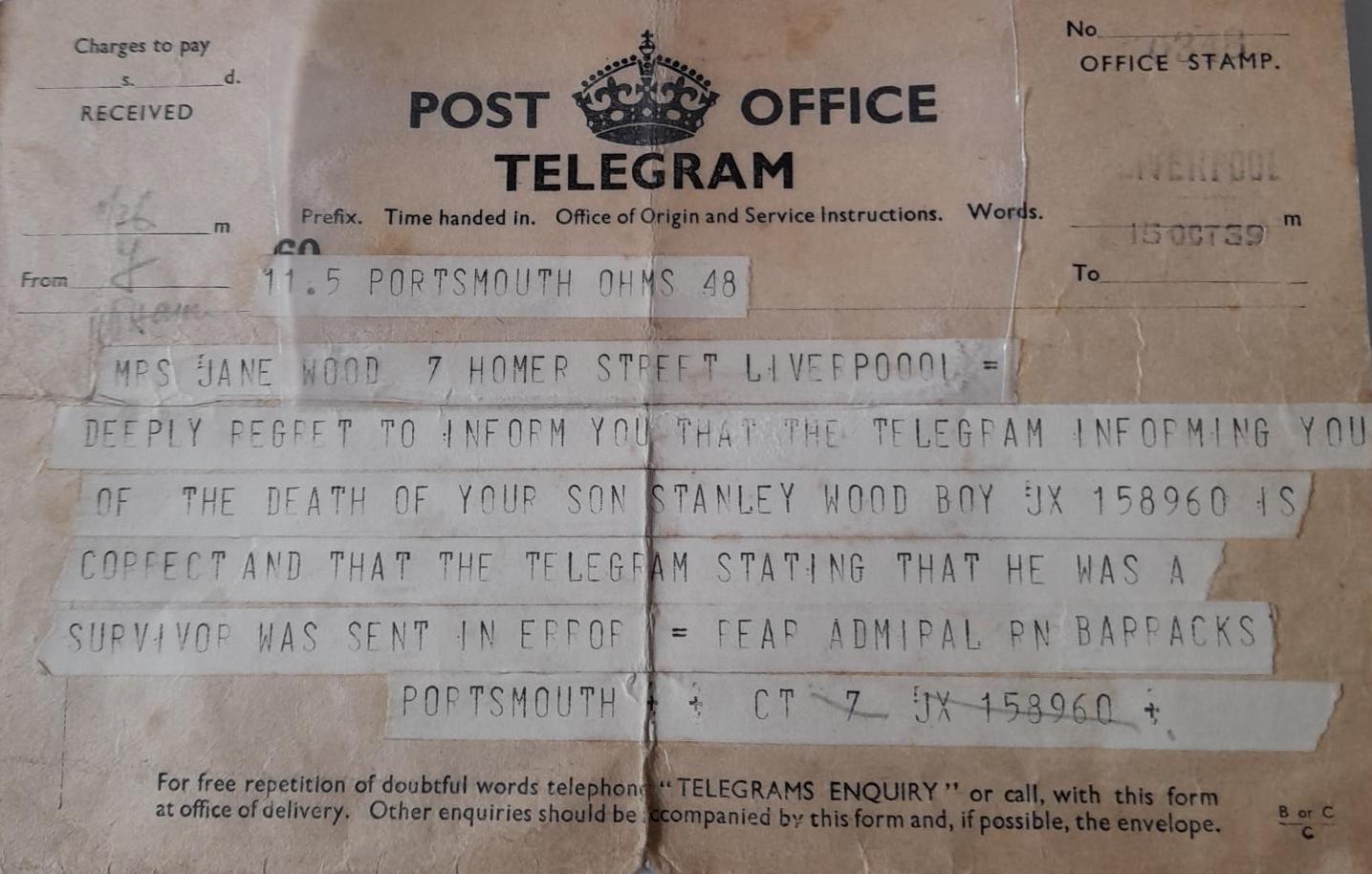

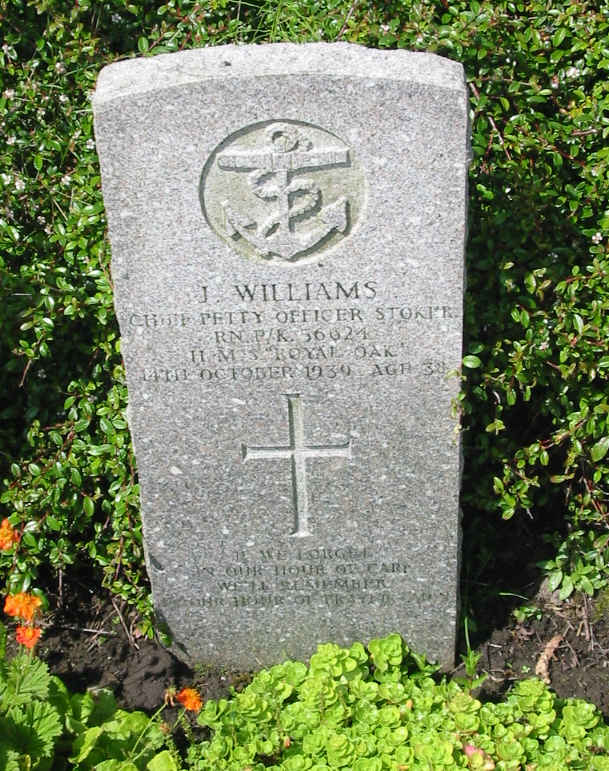

Portsmouth was HMS Royal Oak’s home port, and there, outside the famous naval base, lists were posted of the dead and survivors. For some, there was good news – for most the worst, each man lost a tragedy to his individual family within the wider tragic act. Reflect, if you will, on the story of Boy 1st Class Stanley Wood, a Liverpudlian – one of two Boy Sailors aboard the ship of that name. On 15 October 1939, his widowed mother, Jane Wood, received the official telegram notifying the death of her beloved son. A few hours later, a second telegram arrived, informing the grief stricken single-parent that her son had, in fact, been saved. Her joy can only be imagined – as can the crushing blow when a third telegram came within a matter of hours acknowledging that an error had been made and Stanley was indeed lost. Those casualties whose bodies were found were buried in the naval cemetery at Lyness – Stanley Wood was not amongst them, or at least not known to be so given that a number were never identified, and he, along with many others, is commemorated on Portsmouth’s Naval Memorial at Southsea.

Fast forward to 2003, by which time I had become a very keen scuba diver, mainly to lay eyes on First and Second World War shipwrecks scattered around Britain’s coastline. That summer, my Worcester-based dive club made the annual trek North to dive the German High Seas Fleet wrecks at Scapa Flow. During a break between dives, our skipper, Bob Anderson of MV Halton, took us out to see the buoy marking the wreck of HMS Royal Oak. Having spent years researching and sharing stories of wartime casualties, I was deeply moved to see messages from bereaved families festooning the buoy. Here was a story not yet told: whilst the facts surrounding the sinking of the venerable old battleship have long been known, the individual stories of survivors and the hidden histories of those who died had not – and such stories are crucially important to record. So it was that I resolved to do so. Returning home, I worked with survivor Kenneth Toop, then Hon. Sec. of the HMS Royal Oak Association, tracing 32 families of the 832 souls believed lost – since updated to 835. This led to publication of my first book on the tragedy, which placed the event in context, mainly for families without knowledge of naval or wartime history, to better understand the event. That book, Hearts of Oak: The Human Tragedy of HMS Royal Oak, included numerous accounts from survivors whilst majoring on the stories of certain casualties, collectively representing the ship’s company. This was published by Amberley in 2010, then re-released by the same publisher as a paperback, The Sinking of HMS Royal Oak in the Words of the Survivors, in 2012 (must be said, however, that I was completely unaware of the title change, which suggested that this was a completely new book, which it was not and hence one of the reasons I stopped writing for Amberley).

All these years later, research is so much easier – one of the more positive sides to social media being the innumerable special interest groups and pages on Facebook – amongst them the ‘HMS Royal Oak Families and Friends’ page. Through this medium I was able to trace many more families, and was delighted to learn that although all of the survivors are no all gone, the Ship’s Association is thriving. It was therefore decided to produce a completely new book, majoring on faces and stories of the crew, in cooperation with families and in fellowship with the Association, the current Hon, Sec, Gareth Derbyshire, kindly contributing the Foreword. Annually, moving services of remembrance are held at Southsea, the National Memorial Arboretum and, of course, at Scapa Flow to commemorate the sinking – and I was delighted to learn that the Association has initiated and driven forward plans for a memorial close to Portsmouth’s naval dockyard’s famous gates, which will be unveiled in 2024, the tragedy’s 85th anniversary year. Collectively, then, all of these things, ensures that the Royal Oak story still has currency – which is so crucially important.

This new book, Faces of HMS Royal Oak: The “Mighty Oak” Disaster at Scapa Flow, is, it is fair to say, unique in the Royal Oak’s bibliography and I would urge any other families with material to contribute to contact me via my website, or Facebook, because a follow-up book of ‘new’ photographs could then happen, paying further tribute to those lost at sea that terrible night…

………………………………………………………………..

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS

Order the book here.

Dilip’s website.

Dilip’s YouTube Channel.

Anyone interested in joining the HMS Royal Oak Association should contact the Hon. Sec., Gareth Derbyshire: info@hmsroyaloakassociation.com

HMS Royal Oak Friends & Families Facebook page.