Author Guest Post: James Goulty

Remembering the Korean War and the Ceasefire of July 1953

This year (2023) marks the 70th anniversary of the Ceasefire or Armistice that halted the Korean War, and the 60th anniversary of the ending of National Service (conscription). Both are significant and inter-related, given that many National Servicemen served in Korea. These young men did not necessarily have any natural aptitude as soldiers, but often performed extremely well, and served alongside regulars and recalled reservists. Similarly, in America there was ‘the Draft,’ and many draftees (conscripts) were posted to Korea, as well as regular personnel and reservists.

Today the Korean War (25 June 1950-27 July 1953) is sometimes dubbed the ‘Forgotten War,’ and certainly there’s been a perception among many Korean War veterans that their sacrifices have not received the recognition they deserve. One British soldier recalled coming back from Korea, looking fit and tanned, when a friend asked him: ‘Where have been, on your holidays?’ ‘No Korea’ and the friend didn’t have any idea of what he meant. Likewise, its proximity to the Second World War, might have led Korea to being overlooked. Since the 1950s, it has been overshadowed in the popular consciousness by later conflicts notably Vietnam, the Falklands, and lengthy engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan. An American veteran, who’d served in Korea during 1950-1951, commented: ‘I gotta bad attitude about it, and I hate to say it but I do. Anything you hear today is Vietnam, Vietnam, or Afghanistan but you don’t hear a damn word about the Korean vets.’

Set against a backdrop of global confrontation between Communism and Capitalism, and with the threat the situation would escalate, the Korean War was a significant event of the Cold War, the ramifications of which are still being felt today. When North Korean invaded South Korea in June 1950, the West perceived it as nothing more than a centrally orchestrated plot by the Kremlin. Cold War politics, led President Harry Truman to term Korea a ‘police action,’ something resented by veterans because it suggested theirs wasn’t a ‘proper war.’

Yet, it was a brutal civil war that became internationalized with the intervention of the American led United Nations Command in support of South Korea. British and American soldiers fought together with those from South Korea, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Philippines, Turkey, Thailand, France, Greece, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Colombia and Ethiopia, plus medical units from India and Norway. On the opposing side was North Korea (with support from the Soviet Union) and Communist China. Largely weaponry, equipment and tactical doctrine of Second World War vintage was employed but there were exceptions, notably the British Centurion tank, then one of the most advanced in existence.

UN casualties were approximately 118,000 killed, and over 264,000 wounded, many seriously. Harold Davis, a National Serviceman with the Black Watch was raked by enemy machine-gun fire causing grievous abdominal wounds that required two years of hospitalisation to recover from, although that did not prevent him becoming a distinguished professional footballer! Around 93,000 UN personnel endured a torrid experience as POWs at the hands of the communists. Enemy casualties are harder to quantify, not least owing to their practice of removing their dead from the battlefield, but might have been in the millions.

Troops endured the unimaginable hardship of the Korean climate, with its savage winters, dry, humid summers, and the pitiful sight of refugees in a land ravaged by war, disease and poverty. Typically, the enemy proved wily and tenacious. Their mass attack tactics came as a shock, especially given the enemy’s apparent disregard for casualties. Lieutenant Colonel Colin Mitchell served with 1st Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and observed that ‘soldiers were tested to the limit. If one survived the dangers and rigors of that war, then I believe that one was truly a soldier.’

Crucially, the ground war wasn’t fought in isolation, and from an early stage the UNC established naval and air superiority, enabling fighting to be contained to the Korean peninsula. Consequently, troops were provided with comparatively high levels of close air support, unhindered by the presence of any credible enemy air threat over the battlefront, not something that was likely to be replicated in any confrontation with the Soviet Union. In this regard, the Australian and South African air forces provided significant assistance alongside their American counterparts and the Fleet Air Arm.

Initially, the Americans proved ill-equipped to oppose the North Korean invasion, as units rushed from occupation duty in Japan were typically under-prepared and under-equipped. Over the next few months defeat appeared possible, and would have led to a ‘Far Eastern style Dunkirk’ from the southern port of Pusan. Then in September, UN ground forces broke out of the Pusan Perimeter, in conjunction with an audacious amphibious landing at Inchon, 150 miles to the north, and within striking distance of Seoul, the South Korean capital, altering the course of the war. Troops in the Pusan Perimeter advanced north, and on 26 September linked-up with those who’d landed at Inchon, simultaneously Seoul was liberated after vicious fighting.

By late November, UN troops neared the Yalu River, the Korean-Chinese border, the decision having been made to cross the 38th Parallel, the political dividing line between North and South Korea, and potentially unite the two Koreas. This prompted Communist China to enter the war, and thousands of Chinese People’s Volunteers (in reality hardened troops from the People’s Liberation Army) hurled the UN forces back, in what China termed ‘the war against American aggression.’ Aided by the mountainous terrain, which separated the American Eighth Army advance in the west from that of X Corps in the east, the Chinese were successful. By the end of 1950, the Eighth Army had been forced back to the line of the 38th Parallel, and survivors of X Corps had to be evacuated by sea.

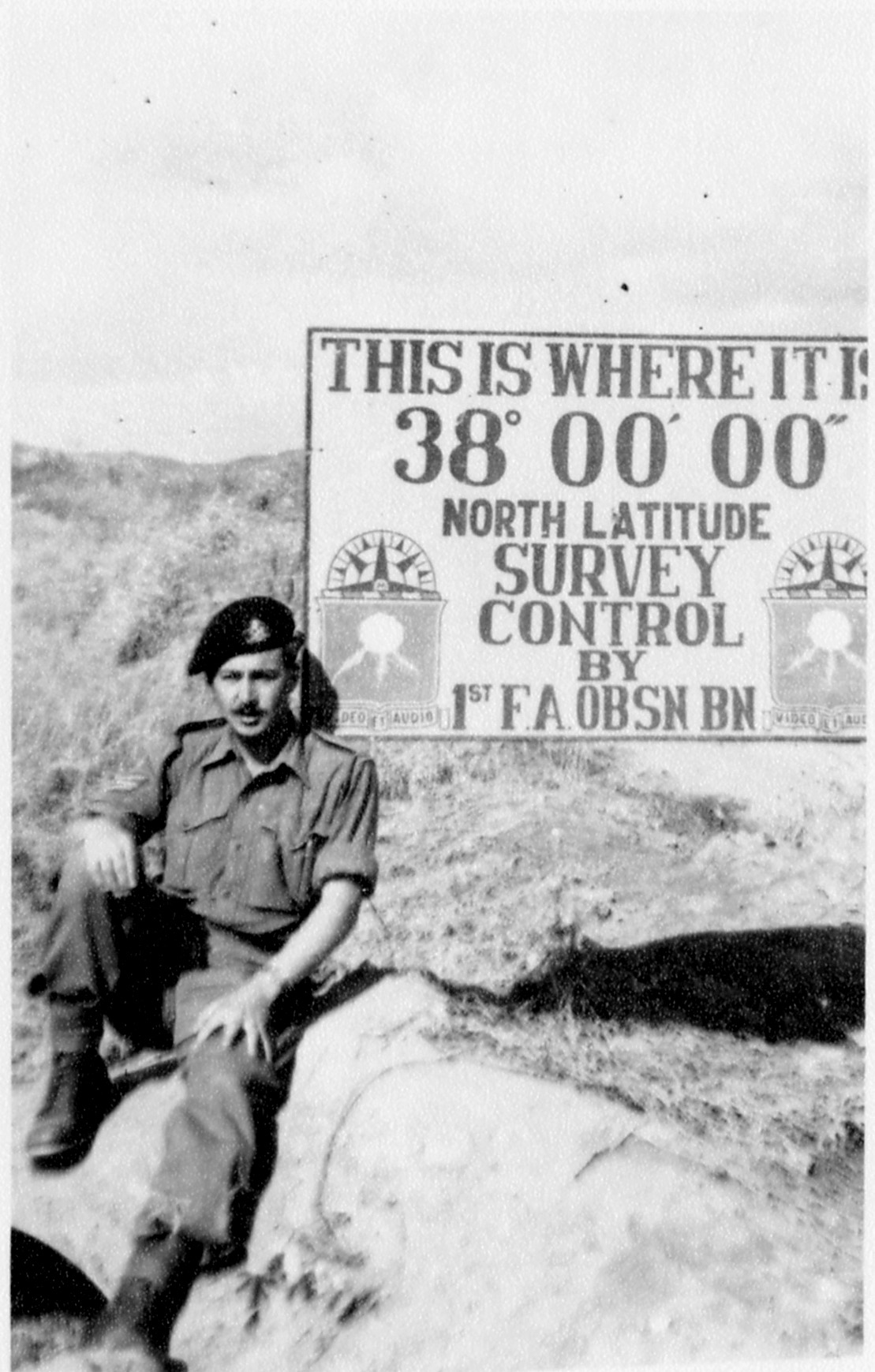

Spurred on by these events, the UNC abandoned the notion of uniting Korea, and was prepared to seek a negotiated settlement. However, first a renewed offensive by the communists had to be confronted during early January 1951. UN forces then launched a series of limited counter-offensives during late January-March, re-taking Seoul, and leading to the frontline stabilising around the 38th Parallel. The fighting then ebbed and flowed in this region for the rest of the war. For the British, the Battle of the Imjin (22-25 April 1951), made famous by the last stand by 1st Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment, and those for the Hook a key feature in the Sami-Chon Valley (18/19 November 1952 and 28/29May 1953), loom large.

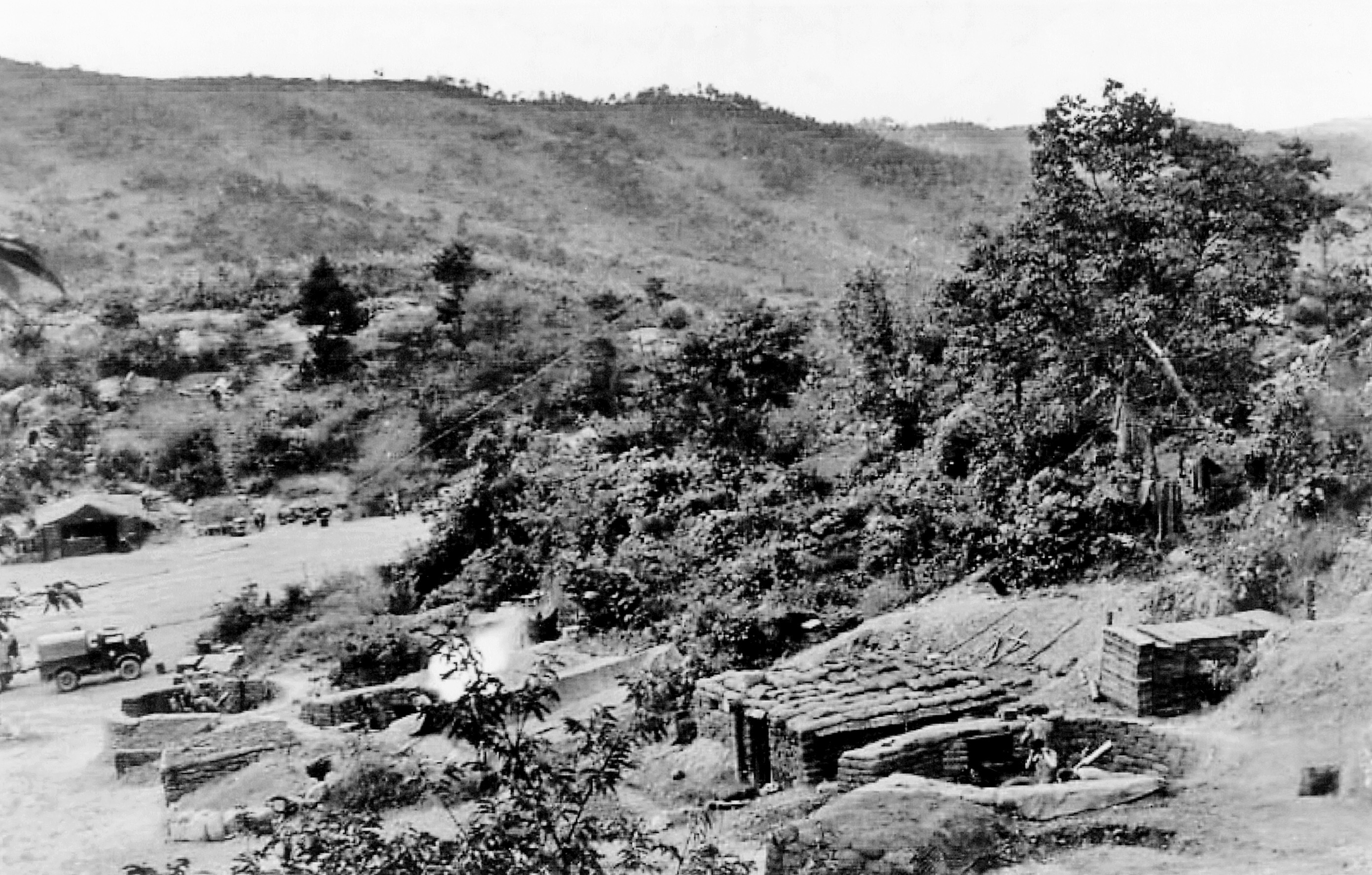

Armistice negotiations commenced at Panmunjom on 12 November 1951, and continued hesitantly for nearly a year. Meanwhile troops endured static warfare, increasingly reminiscent of the First World War. There was an emphasis on battles for significant terrain features, such as Pork Chop Hill, and nerve-wracking patrolling and raiding, mostly by night.

On assuming the presidency in early 1953, Eisenhower was determined to end the war, and peace talks resumed, leading to the eventual ceasefire agreement of 27 July. Although the negotiations had been ongoing, the suddenness of the Armistice caught many soldiers by surprise. Brigadier Brian Parritt, then a more junior artillery officer, recalled orchestrating a ‘Victor’ or corps sized shoot shortly before hand, the idea being that the UNC wished to demonstrate that although they would sign the agreement, they were prepared to continue fighting if necessary. Likewise, an American soldier with 2nd Infantry Division on the frontline on the eve of 27 July noted how the Thai unit on their left flank began intensive firing, perhaps loosening off all their ammunition so it did not have to be carried away. News soon filtered through to troops that the UNC had agreed a ceasefire with the communists at 10.00 hours 27 July 1953, to become effective at 22.00 hours.

On standing down there was rejoicing as the guns and mortars fell silent. A British gunner manning a Command Post remembered ‘wild celebrations’ with much consumption of Asahi beer and enthusiastic, if discordant singing. Others in the frontline let off flares or fired smoke bombs in response to similar initiatives by the enemy. Contrastingly, some soldiers experienced less cause for celebrating, and more of an intense sense of relief that the killing seemed over, tempered by the realisation that they had to be prepared to resume fighting should the Armistice Agreement break down or be violated. Mixed with this was uneasiness at the sudden uncanny calm, punctuated by the noises of Korean wildlife, which had previously been obscured by combat. Some could not cope with this sudden cessation of hostilities, and the absence of the adrenaline rush of active service. One British soldier, who had received the Military Medal for bravery, flung his kit in the River Imjin, and had to be evacuated as a psychiatric casualty. Another aspect, observed by some officers, was that troops released from the strains of war, started to adopt a ‘skiving’ attitude towards their employment, more akin with peacetime.

In some units the Armistice gave rise to fraternization with the enemy, albeit officers were discouraged from this. The American infantryman Carl Ballard, who served during the latter phases of the Korean War, was interviewed by Grand Valley State University. He recalled that initially he was scared by the eerie silence, and wondered if the Chinese were up to something. However, at dawn the next day there was a sense of relief:

…the Chinese were out. They’d probably not seen the sun for a year or however long they were there because if they popped their head out we would have blown it to pieces. And they were sunning themselves and washing their clothes and waving back and forth when the night before we’d have been shooting at them. Some guys went over and gave them cigarettes. It just shows you, you’re not fighting the people, it’s the governments-governments are doing this. You had no personal feelings against that Chinese man over there or that North Korean but you’re doing your job and they’re doing theirs. That was it.

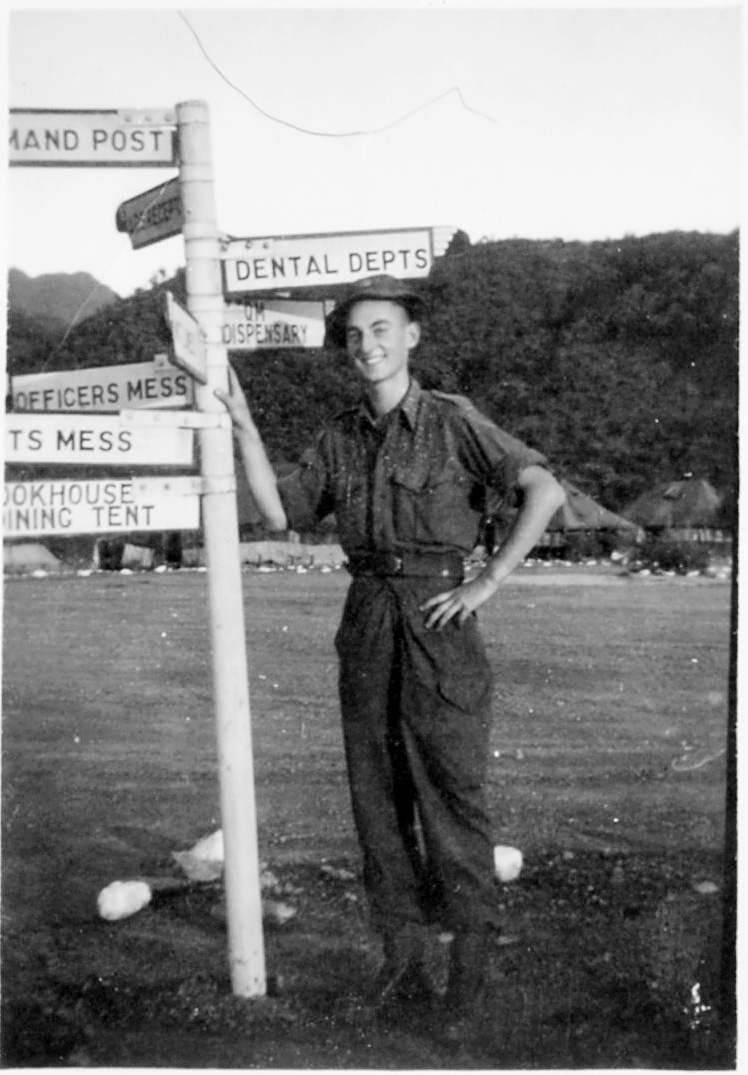

Shortly after the Armistice, both sides agreed to withdraw two kilometres from the line of demarcation, and establish a Demilitarized Zone. In the case of 1st Commonwealth Division, it withdrew to an area north and south of the River Imjin. Training rapidly commenced in case there was a resumption of hostilities, with an emphasis on offensive and defensive operations, including patrolling, a distinct feature of fighting in the latter stages of the Korean War. New defensive positions and accommodation had to be prepared ahead of the Korean winter, and to maintain morale provision made for rest and relaxation. Likewise, positions on the old frontline had to be destroyed, and weapons, ammunition and stores removed, which was a considerable undertaking. The gruesome task of recovering bodies was another pressing concern.

The British Army maintained a presence in Korea until the late 1950s, and the American military continues to this day to support South Korea. There has been no formal end to the Korean War, and some veterans wonder what it was all about, given the war ended as it began with a divided peninsula. Others remain proud that they thwarted communist aggression. Despite several serious incidents since 1953, the Armistice has largely held. In April 2018 the Panmunjom Declaration was signed by the leaders of North and South Korea with a view to seeing the denuclearisation of the peninsula and working towards a formal end to the war.

To read more about the experiences of British and American troops during the Korean War, 1950-1953 please see my book: ‘Eyewitness Korea’ and thanks to the publisher Pen and Sword Ltd.

James Goulty