Author Guest Post: Norman Ridley

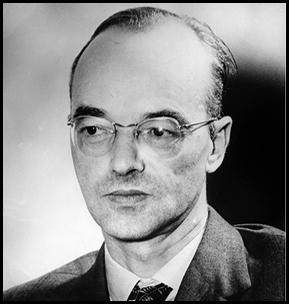

Klaus Fuchs; Soviet Spy

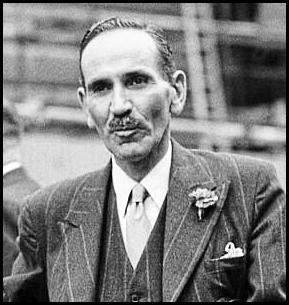

In September 1949, four years after the end of the Second World War, the British MI5 counter-espionage agency received information that a British scientist working in the Physics Department at the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment had been passing classified information to the Soviet Union for at least seven years. It was thought that they had become aware of this treachery thanks to US ‘Verona’ codebreakers but recent research has suggested that it was the British GCHQ cryptanalysts who had been reading the Soviet signals. In December, the ex-Scotland Yard officer turned MI5 chief spy catcher, William ‘Jim’ Skardon, called in Klaus Fuchs for one of his ‘cosy chats.’ So as not to scare Fuchs off, Skardon told him that it was just a routine vetting interview since, Fuchs’ father had recently been offered a teaching post in the Soviet Zone of occupied Germany.

Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs had been born in Rüsselsheim on December 29, 1911. He studied mathematics and physics at the University of Leipzig then the University of Kiel and joined the German Communist Party (KPD) in 1930. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, to avoid persecution, Fuchs fled to England where he found work as a research assistant at the University of Bristol before received his Ph.D. in physics in 1937. After graduation, he moved to the University of Edinburgh and began working under Max Born.

Skardon began in his usual avuncular way talking about this and that and just occasionally referring to the purpose of the meeting. Then towards the end he said ‘While you were in New York, I believe you were in touch with representatives of the Soviet Union, were you not?’ Fuchs was startled, took off his glasses, polished them then put them back on and said, ‘I don’t think so.’ ‘Don’t worry,’ said Skardon, ‘tell us all about it and there’s every chance you can get back to work without any risk of further repercussions.’

Fuchs had been granted an unlimited residency permit in 1938 but still had his application for British citizenship approved when the war had broken out. He was subsequently interned as an enemy alien and sent to a camp in Canada. Ever since he had arrived in England, MI5 had him marked as a potential security risk for his communist background and it was known that he had made contact with Jürgen Kuczynski the rather well-connected head of the British branch of the KPD. His old university professor was able to secure his release from detention and Fuchs returned to Britain where he resumed his work in Edinburgh. Two things happened in 1941 that would change Fuchs’ whole life. He was co-opted to work on the British atomic research project and German forces invaded the Soviet Union.

On their fourth meeting, Skardon sensed that Fuchs was ready to talk, took him to the Queen’s Hotel in Abingdon, treated him to a hearty lunch then sat back as Fuchs told all. ‘The Soviets were not our enemy,’ Fuchs said, ‘How can it be treasonous to help an ally?’ Skardon agreed that it was a valid argument. In Fuchs’ eyes, the Western Allies had chosen to let the Soviets and the Nazis slaughter each other on the Russian Steppes and fight the war to a bitter end after which the British and the US would go in and pick up the pieces. He felt under an obligation to help the Soviets in any way he could. Skardon did not disagree and let the story unfold.

What Fuchs believed had been a chance meeting with Kuczynski in 1942 led him to start passing snippets of information about the British bomb project to Kuczynski’s sister Ursula, a Soviet agent, codename ‘Ursula’. The process was like something out of spy fiction. Fuchs would mark page 10 of a magazine, then throw it into a London garden to set up a meeting with the KGB. His Soviet handler responded with a chalk mark on a local lamp post. All went smoothly until Fuchs was suddenly whisked away to Columbia University in New York to join up with the Manhattan Project, the US atomic bomb programme. Once there he was approached by his new contact, Harry Gold, codename ‘Goose’. More spycraft as Fuchs sauntered to his first rendezvous off East Broadway carrying a green book and a tennis ball. He approached a man in a dark suit and overcoat wearing gloves and carrying a second pair in his hand and asked him for directions to Chinatown. ‘I think Chinatown closes at five-o-clock,’ the man replied. Soon Fuchs was off again, this time to Los Alamos to work on uranium enrichment. His work involved calculating the approximate energy yield of an atomic explosion. In June 1945, just before Trinity test, he passed along a sketch of the bomb, providing its components and dimensions, and described the design in great detail. After the war, Fuchs returned to England and continued his work on the British atomic bomb project as the head of the Physics Department at the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment.

After his confession, Fuchs was arrested but Skardon had been less than truthful. Instead of going back to work, Fuchs was charged with violating the Official Secrets Act. Given a 14-year prison sentence, he served only 9 before being released and allowed to go to East Germany where he was granted citizenship and appointed Deputy Director of the Central Institute for Nuclear Research at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf laboratory. He was additionally a member of the East German Academy of Sciences and the 1979 recipient of the Karl Marx Medal of Honour, the highest distinction in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) for exceptional merit. He retired in 1979 and died on 28 January 1988 at the age of 76 in East Berlin.

Order your copy of The Race for the Atomic Bomb here.