True Crime: The murder of Elizabeth Ridgley

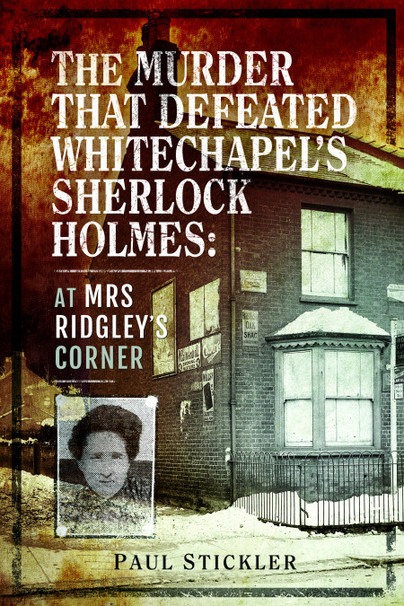

Today we have a fascinating guest post from Pen and Sword author, Paul Stickler. Criminologist and historian Paul describes the incredible circumstances surrounding the murder of Elizabeth Ridgley in Hitchin, Hertfordshire in 1919 in his newly released title The Murder that Defeated Whitechapel’s Sherlock Holmes. Read on as he offers us a glimpse into the horrors of the murder and the frailties of rural policing just after the First World War. Enjoy!

When you’re sniffing around dusty archives endeavouring to research a particular piece of criminal history – in my case, unusual or unexplained murders – occasionally you unearth a crime which stares back at you in an inviting way. This was certainly the case when I stumbled across a set of photographs and mis-filed papers in a Hampshire archive in 2014. I immediately knew, by virtue of a photograph of a prisoner in the dock and another of the flamboyant pathologist Bernard Spilsbury, that this was a murder. A little more research led me to the conclusion that this was no ordinary murder and that it had largely been ignored or simply just not written about. That had to change.

Briefly, in 1919, when Britain was trying to rebuild itself after the First World War, a 54 year old woman, Elizabeth Ridgley, was alone in her corner shop in Hitchin, accompanied by her Irish terrier when she was brutally attacked with a four pound weight. Her dog received the same treatment and both were left for dead. The killer then ransacked the property, stole cash and left blood scattered throughout the shop and the living area. He then made good his escape through the backdoor and disappeared into a very cold and snowy night.

What made this case so interesting was that the local Hertfordshire police, who were alerted to her death two days later, quickly arrived at the conclusion that Mrs Ridgley had somehow died as a result of a tragic accident. The explanation as to how her dog died was even more bizarre. Suffice to say, Mrs Ridgley’s body was buried in an unmarked grave and the locals were left to mourn the death of one of their own. Just to add to the mix, the local police superintendent allowed the family to continue trading at the shop and every single piece of bloodstained property, some bearing obvious fingerprints, were washed away.

It would be fair to say that policing in the provinces after the First World War was in a bit of a mess. For the past four years they had focussed on war legislation such as food rationing, lighting regulations and oddities such as women fraudulently claiming widows’ pensions as well as the odd scare about German spies living among them. Detection of serious crime was dealt with in a rather ad hoc way. But there could be little excuse for interpreting two broken skulls, an obvious murder weapon, a heavily bloodstained scene spread throughout several rooms and a ransacked till as anything other than a murder.

The Chief Constable, Alfred Law, already under immense pressure for other reasons decided to call in Scotland Yard to review the matter hence the appearance of Bernard Spilsbury alongside, who the newspapers described as ‘probably Britain’s cleverest detective’, Fred Wensley. Having exhumed the body of the poor shopkeeper, murder was quickly confirmed with Spilsbury even being able to show that having been struck across the skull, Ridgely, in an unconscious state, was dragged by the hair around the house.

Wensley, an experienced and successful detective from the East End of London reconstructed the scene as best he could and told the newspapers that this was now a murder investigation. Within nine days Wensley headed for a property only 200 yards away from where Ridgley met her death and arrested an Irish war veteran, a man with an extremely violent past and who had recently been exposed to the atrocities of the war in Europe.

The evidence started to pour in and the man arrested, John Healy, found himself on trial at Hertford Assizes accused of murder. Wensley had recovered the situation by bringing to bear all his training and experience from the capital though he would admit, he was much exercised about the earlier investigation when he had first set foot in the small market town. The Home Office had been encouraging rural forces to contact Scotland Yard in cases of complex investigations but on this occasion, had they pushed the alarm button too late? Had the damage already been done? Strong circumstantial evidence – including witnesses who saw Healy inside and outside of the shop at the time – and proof that he had lied about his whereabouts on the evening of the murder was a reasonably strong case. The jury though thought otherwise and after a short deliberation of only twelve minutes, they acquitted the Irishman.

So, who killed Mrs Ridgley? Was it Healy? Had he been seen as a war hero who deserved not to hang? Did the long line of prosecution witnesses all conspire to convict the passing visitor to the town merely because he was Irish? That was certainly Healy’s opinion particularly as this was a time when the Irish Home Rule issue was at its peak. The papers I found in the archive threw no extra light on the matter. But, just as my pen was drying, I found some more documents – and they were enlightening.

Quite apart from the original police report which argued without reason that Ridgley died as a result of an accident, a new name appeared in the middle of another report, written after the acquittal of Healy, which had not featured in the Hertfordshire or the Metropolitan investigation. This man had been spoken to by Hertfordshire officers, if not on the day of the murder, certainly within the first few days. He had been questioned by a police inspector. His full name was there in black and white, yet he did not feature in the investigations that followed. To add to the mystery, despite Wensley conducting a good investigation in the light of all the lost evidence, when I read the statements, it was apparent that another man was seen inside the shop just before the murder. He was never identified. Who was he? Was it the same man mentioned in the police report?

There are many more twists on the way – a suicide of a police officer, the accidental shooting of a member of the public by a police officer and articles from the scene being accidentally damaged. Rural policing had to change. And, slowly it did. As the country crawled its way to a second world war, police forces started to appoint and train detectives, and of course forensic science developed. Not because of this case, but the Hitchin corner shop killings undoubtedly shaped the way future murder investigations would be carried out.

RIP Elizabeth Ridgley

More information can be found about Paul Stickler’s work here.

The Murder that Defeated Whitechapel’s Sherlock Holmes is available to order now.