Author Guest Post: James Goulty

The Second World War through Soldiers’ Eyes: British Army Life 1939-1945

The ‘Second World War through Soldiers’ Eyes,’ has now been published by Pen and Sword in both hardback and paperback formats-for which I am extremely grateful. The text combines narrative with eyewitness or first-hand material, to provide what I hope is an engaging, interesting and vivid read on what it was like to serve in the wartime British Army. Additionally, the book hopefully provides a fitting tribute to the wartime generation of soldiers that are sadly rapidly fading away.

The onus is very much on the experiences of ordinary soldiers and officers at regimental level or the equivalent. British soldiers fought in a variety of theatres around the globe during the war, ranging from north-west Europe to Burma. Equally, many spent considerable periods in Britain, either training or on other duties. Thousands of women also served with the Auxiliary Territorial Service or ATS, and the book contains a section devoted to them. These men and women came from a generation that had grown up in the shadow of the First World War, and a Britain that had not yet relinquished her position as an imperial power. Many volunteered, but as the war progressed increasing reliance was placed upon conscripts, some of whom proved more willing warriors than others.

Initially, the British Army was underprepared for war, particularly against a major European power such as Germany. However, by 1944 it had evolved into an effective fighting force, that ultimately emerged victorious and fully played its s part in the overall Allied war effort.

Chapter one entitled: ‘Call-up and Training’ highlights the role of the training process in rejuvenating the wartime army, and considers what it was like for men and women when they volunteered for military service or were conscripted. Consideration is also given to the experiences of Regular Army personnel and soldiers from the Territorial Army who served in the war. There are sections on key areas, such as receiving a medical, basic training, training for particular trades, and officer selection and training. Infantry training also features, notably the role of battle drill in imparting tactical knowledge and preparing troops for battlefield conditions.

The second chapter deals with life on active service, and commences by discussing life aboard troopships, as in the 1940s, this was the main method by which soldiers were transported abroad. Typically, officers enjoyed a comfortable existence aboard these vessels, whereas, conditions were usually harsh for other ranks crammed aboard in an atmosphere of stale sweat and vomit, unsure of what the future had in store. The chapter goes on to highlight the nervous tension felt by many before going into action. As an experienced NCO from the Royal Horse Artillery commented, there was ‘a surge of adrenaline as the panorama of battle surrounded us.’ Further discussion outlines battlefield conditions in different theatres that British soldiers experienced, and draws attention to important areas, including patrolling by infantrymen and the experiences of armoured and artillery personnel.

Contrastingly, chapter three examines how soldiers coped with active service, and highlights factors that made life more bearable. Combat personnel in particular risked psychological and/or physical injury on the battlefield. Even soldiers from non-combatant units, not directly involved in the fighting, could come under fire or aerial bombardment, and like combat troops, active service for them often entailed a lack of comfort, plus the pressure of being away from home and loved ones. Notably, the chapter discusses disciplinary issues, battle exhaustion, desertion and self-inflicted wounds, which for those desperate enough potentially offered a way out. Attention is also given to welfare and entertainment; food, cooking and rations; drinking and drunkenness; plus love romance and sex.

Chapter four reviews the experiences of POWs. The capitulation of France and the Low Countries in May/June 1940 yielded 34,000 prisoners from the British Army alone. As the war continued, thousands more were captured in North Africa during 1940-1943, and wound up in POW camps in Germany or Italy. The Germans also captured British troops in Norway 1940 and Greece 1940-1941, while in February 1942 around 90,000 troops were captured when the Japanese took Singapore, to add to those already captured elsewhere in the Far East. Discussion considers the bewildering conditions of being taken prisoner on the battlefield, the degradation usually suffered while being transported to a POW camp, and conditions in the camps themselves. Further consideration is given to how personnel coped with their captivity, such as what they ate, and the role of escape and evasion. Contrary, to the popular image, reinforced by the silver screen, there was nothing glamorous about becoming a POW in the Second World War, and prisoners typically endured horrendous conditions, especially in the Far East, that many of us who have grown up since 1945 might find hard to imagine.

Chapter five outlines the vital role played by the army’s medical services during the war and draws upon the experiences of individual soldiers, army doctors, female nurses and other military medical personnel. At the outbreak of war the army had one of the most advanced medical systems in the world, as exemplified by the introduction and development of an effective blood transfusion service, when techniques for carrying out such procedures were still in their relative infancy. Advances were made in the treatment of broken bones, and penicillin deployed for wounded or sick troops. The treatment of burns posed a challenge, particularly amongst tank crews, and soldiers burnt while cooking, as they routinely relied on petrol fuelled stoves.

Another element to the chapter underscores that significant casualties in all theatres resulted from accidents or disease, rather than enemy action. Ultimately, soldiering, even when not in contact with the enemy, could be dirty, dangerous, and demanding. The importance of health and hygiene is therefore emphasised, as the army encouraged troops to take precautions against diseases and insanitary conditions, especially in awkward theatres such as North Africa and the Far East.

Finally, there’s a section called: ‘The Aftermath, c. 1945-1946.’ This considers the challenges facing the army during the immediate post-war period, and focuses on soldier’s memories of the end of the war. It also discusses experiences of the demobilisation process, and veteran’s reflections on the war and their military service.

This was an extremely enjoyable and moving book to research and write. Research took me to county record offices/archives, where regimental collections and/or the personal papers of wartime personnel were held. Public libraries also proved valuable, and notably it was a boon to discover a veritable ‘treasure trove’ of regimental histories stashed away at Newcastle Central Library. Likewise, the oral history collection held by the Imperial War Museum was an extremely useful source on the personal experience of wartime soldiers from a variety of backgrounds. So were a wide variety of published personal memoirs, plus various histories, chapters and articles. Details of these, and all the other sources consulted can be found in the book’s bibliography.

The ultimate highlight was being able to have talks/interviews with veterans. This included Bill Ness, a former paratrooper, and the subject of a separate blog. Three in pensioners at Royal Hospital Chelsea also kindly offered assistance. These were: Bill Moylon, who served with the Royal Army Ordnance Corps and became a FEPOW; Bob ‘Killer’ Taylor who served with the Commandos; and Bill Titchmarsh, a former wartime infantryman, whose experiences you can also read about in my book ‘Second World War Lives.’ James Goulty

The Second World War Through Soldiers’ Eyes is available to order here.

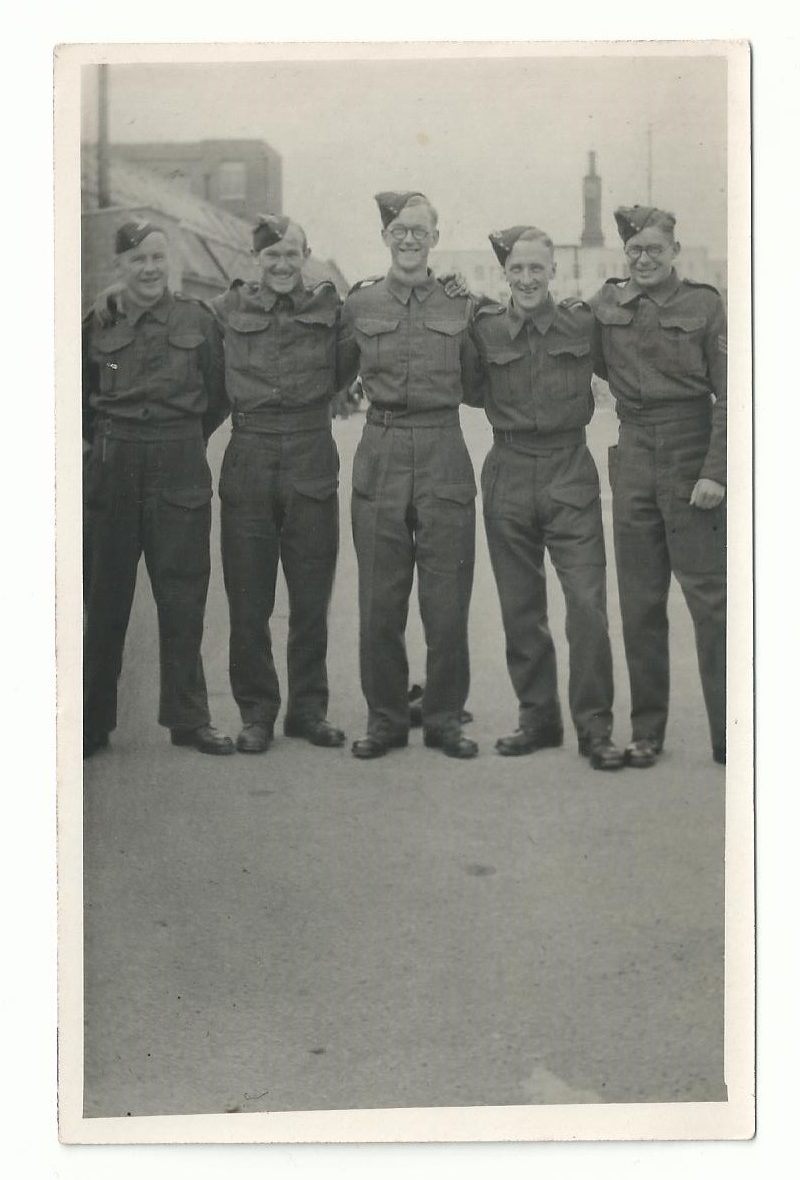

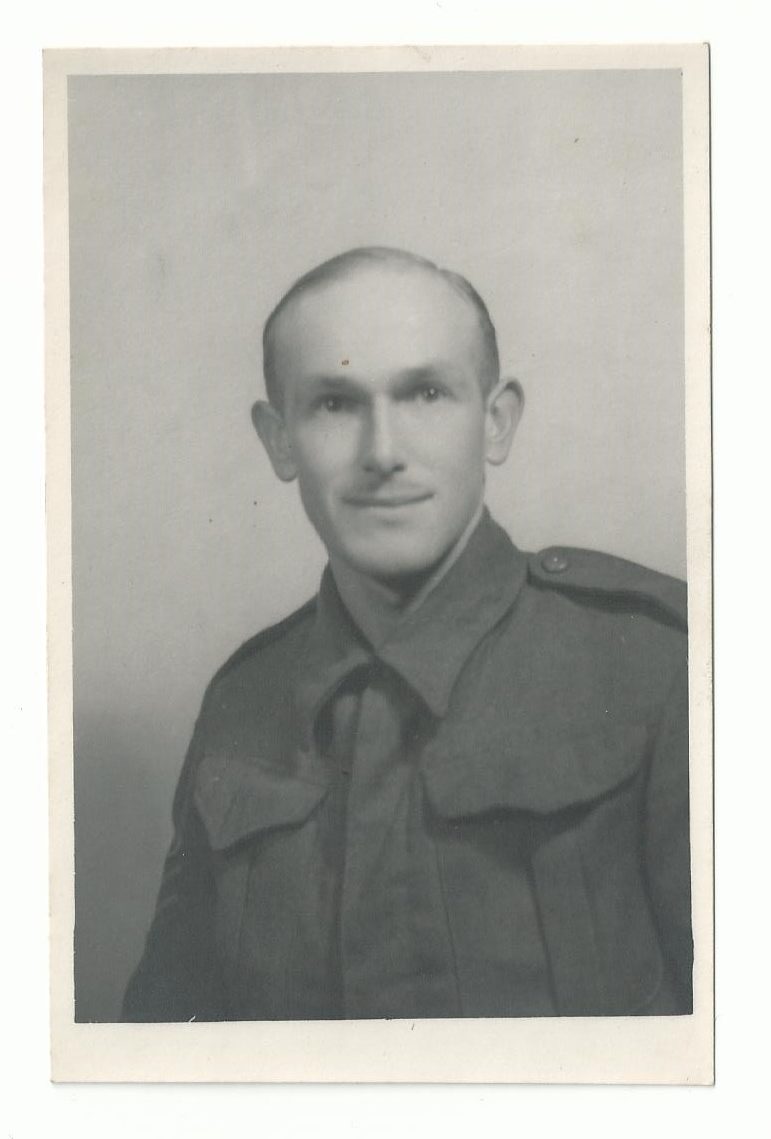

All photos are from the author’s collection.