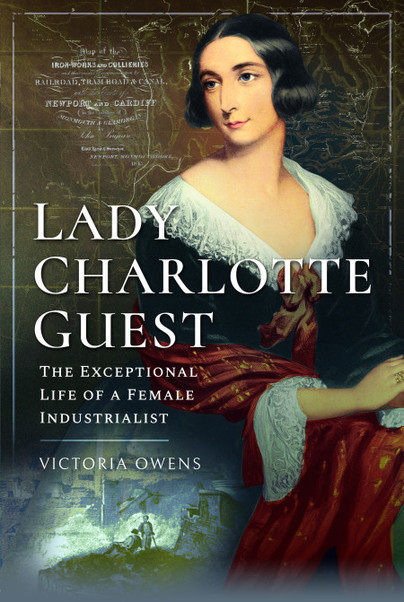

‘…a mere woman’ – Lady Charlotte Guest (1812-1895), Translator and Ironmaster

Author guest post from Victoria Owens.

‘I have taken up such pursuits,’ observed Charlotte Guest in October 1836, ‘as in this country of business & Iron making would render me conversant with what occupied the male part of the population …. but every now and then I am painfully reminded that, toil as I may, I can never succeed beyond a certain point, and by a very large portion of the community my acquirements and judgements must always be looked down upon with contempt, as though of a mere woman.’

Behind this cri de coeur lay some after-dinner talk about land-purchase in which she and her husband John had had a slight disagreement. When Charlotte appealed to John’s brother Thomas, who was with them, to take her side, he only laughed, saying that he would never discuss such matters with his wife. The conversation soon turned to other topics, but the assumption that a woman’s view on a serious subject was not worth having stung Charlotte deep, and – she confided in her journal -‘clouded all that evening.’

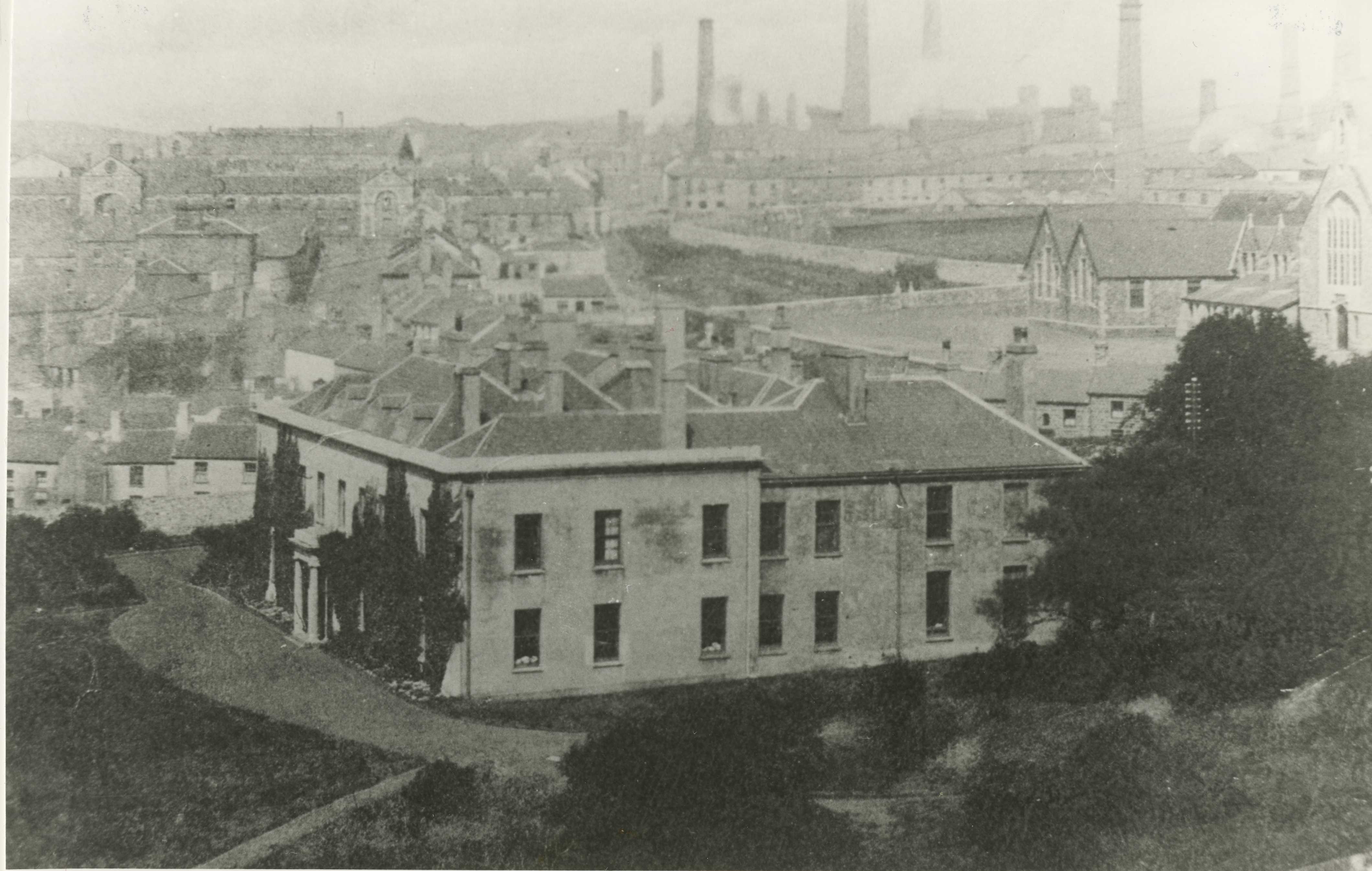

Certainly the achievements her life give the lie to Thomas Guest’s dismissive attitude. Daughter of Albemarle Bertie, 9th Earl of Lindsey and his wife Susanna, she had always been ambitious and gave herself ‘almost a man’s education from the age of twelve.’ It included teaching herself Latin, Greek, French, Italian, Hebrew and Persian from the books in the well-stocked library of her childhood home – Uffington House near Stamford in Lincolnshire. When a copy of Sir John Richardson’s Grammar of the Arabic Language that she had ordered arrived at the Stamford stationers, she was ecstatic; ‘Had there been a heaven higher than the seventh,’ she reflected, ‘I should have been placed in it.’ In July 1833, she married John Guest, ironmaster and MP for Merthyr Tydfil whom she had met less than three months previously. A self-made man twenty-seven years her senior, she adored him. Dowlais, his home and the site of his business empire, was a squalid village, high on a bleak escarpment; from the moment of her arrival, when first she saw the furnaces blazing beneath the night sky she took the place straight to her heart. Within a few days, she began to learn Welsh.

In December 1834, she began to translate Armand Dufrenoy’s treatise Sur L’Emploi di l’air chaud dans les usines a fer de l’Ecosse et de l’Angleterre [On the use of hot air in the ironworks of England and Scotland]. If it sounds a dry subject, to the nation’s ironmasters – few of whom had any knowledge of French -this state-of the-art survey of British iron manufacture held powerful interest. Translating the text gave Charlotte remarkable insight into the technicalities involved in iron production, which would stand her in good stead for the future. In 1836, John Murray published her finished work as a modest octavo costing 5s 6d and although it came out anonymously, the translator’s identity soon became known. The Merthyr Guardian applauded Charlotte for ignoring ‘temptations to indolence’ and ‘frivolities of fashion’ and devoting herself to ‘works by which mankind may be benefitted and the interests of Science advanced.’ That US engineer Samuel Vaughan Merrick’s translation of Dufrenoy’s work which appeared in the 1835 Journal of the Franklin Institute would have evoked such comments seems unlikely.

John and Charlotte had ten children in total and the remark ‘another dear baby has been added to our family’ – or words to that effect – recurs throughout Charlotte’s journals. But her fascination with industry never abated. She and John attended the annual meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and when they were at home in Dowlais, she took daily walks through the works. It was entirely characteristic that she spent the afternoon before the birth of Thomas Merthyr, the couple’s second son, watching her husband experiment with using raw coal in the furnaces rather than the more usual coke.

As the family grew, so did the works. At the height of its power, Dowlais was the largest ironworks in the world. It required efficient transport-infrastructure and, losing patience with the leaky, stoppage-prone Glamorganshire Canal, John took the lead in promoting a railway between Merthyr Tydfil and the Cardiff docks. When he became its first Chairman, Charlotte was invited to lay its first stone. At a ceremony in August 1836 at Pontypridd, the railway committee men gave her a minute little trowel with which she made play of setting the stone slab in its place. But when they offered her a tiny, toy-sized hammer with which to hit it home, she – in her own words – ‘rebelled outright.’ Seizing a wooden mallet from one of the watching labourers, she swung it against the block with all her might. If she intended it to be a riposte to the era’s tendency to treat women as infants, it backfired somewhat; the Merthyr Guardian had a good laugh in print at the ‘workmanlike manner’ in which she executed the task.

Between 1838 and 1849, Charlotte compiled her pioneering edition of the mediaeval stories that have come collectively to be known as the Mabinogion. Not only would she provide the text of each story in both modern Welsh and English, but she also included copious annotation, engaged engravers to devise woodcut illustrations and supplied facsimiles of the variants of each tale, employing a handwriting expert to copy their manuscript sources. Its appearance in 1849 – a sumptuous three-volume edition with leather binding and gilt edged pages – gave solid evidence of her powers as scholar and linguist.

John died in November 1852 leaving Charlotte distraught. To commemorate him, she commissioned Palace of Westminster architect Sir Charles Barry to design a library for the Dowlais employees. But ‘Work – work’ she ordered herself, and hoping to reduce payday drunkenness, she arranged for her labourers to be paid in the village’s schools rather than its inns. She also set about increasing her collieries’ efficiency; locating new sources of ore, and – crucially – replacing the dilapidated locomotives of the ironworks’ railway. A listening boss, she heeded engineer Samuel Truran’s complaints about attending sites ‘scattered over the mountains’ and provided him with a pony at the Company’s expense – in effect, the 1850s equivalent of a company car.

Her greatest challenge came in the summer of 1853, when in common with the employees of other Merthyr works, the Dowlais miners (who mined ore) and colliers (who mined coal) struck for a higher wage. Dowlais had a tradition of paying more generously than its commercial rivals and this ‘Dowlais differential’ counted for much with the workforce. While Charlotte was willing to sanction a modest pay-rise, since the market for iron had slumped, she could not meet their terms in full. In the ensuing clash, determined that the strikers’ should not imagine that, being a woman she would give way easily, she took the drastic decision to put out the furnaces. Perhaps it was unwise; once a blast furnace has been extinguished, restoring it to utility tends to involve a rebuild. Nevertheless, her resolution impressed the other Merthyr ironmasters who agreed to subsidise Dowlais’s losses. After eight weeks’ resistance, persuaded by the promise of a very small bonus, the strikers returned to work. If it was a victory, success did not ease Charlotte’s loneliness. On the anniversary of John’s death, she sadly contrasted the ‘long, happy years’ of her marriage with her ‘present, difficult position’ as head of the works.

During the strike, her eldest son’s tutor – a young Cambridge graduate named Charles Schreiber – fell ill. Somehow, Charlotte found the time to nurse him back to health, befriending him the while. Before long, she fell in love with him. In 1854, after much discussion with her lawyers, she placed the works in the care of energetic trustee George Thomas Clarke and married Schreiber the following year. It marked the end of her time as an industrialist but began her career as a collector of fine china and specialist in the history of fan-making and decorative playing cards. Lady Charlotte died in January 1895, aged eighty six. The Schreiber collection of porcelain and objets d’art is now held by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Lady Charlotte Guest is available to order here.

……………………………………………………………………………………………….

Upcoming event: Join Victoria Owens on the 21st May 2022 for a talk about Lady Charlotte’s life and work. The event will take place at Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Brecon Road, Merthyr Tydfil CF47 8RE, beginning at 2pm. Tickets cost £2 each and places must be booked in advance via this booking link.