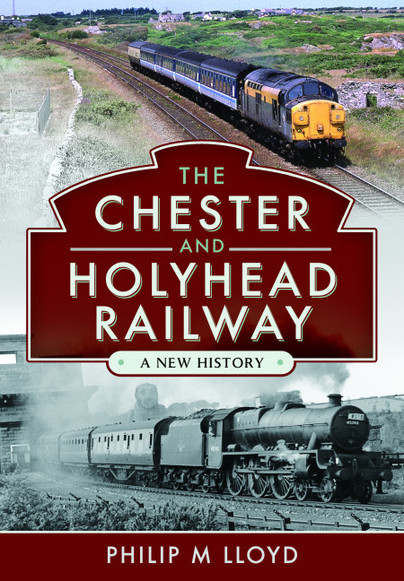

The railway and conflict – a theme in a new book about the Chester and Holyhead Railway

Guest post from author Philip M Lloyd.

November is a month in which the United Kingdom and many other countries remember the pain and sacrifices of conflict. This is a theme covered in my book The Chester and Holyhead Railway: A New History published by Pen and Sword this month. At the heart of the plans to construct the railway was the notion of resolving a long-standing conflict by cementing Ireland into the United Kingdom after the Act of Union of 1801. The book shows how the government in London hoped to use the railway for this purpose and how those hopes were dashed soon after the line opened fully in 1850.

Subsequently the line featured in the continuing struggle of the so-called ‘Irish Question’ for the remainder of the century. There was a plot to capture a train in 1867 and load it with arms stolen from Chester Castle that were to be taken to Dublin to support an uprising. Thereafter, there were a number of scares that are considered in the book that involved fears by the authorities that there would be attacks on the line’s infrastructure or an attempt on the life of a senior UK politician. When trouble flared in Dublin at Easter 1916 and then after the end of the First World War, the line from Holyhead was a conduit for troops and equipment in one direction and prisoners in the other. It also carried the Irish negotiators between London and Dublin as a settlement was finally reached – the centenary of which occurs in December this year.

As the nineteenth century progressed the line from Chester to Holyhead began to serve UK military and political interests in a wider sense. North Wales was an area chosen for camps at which troops were trained for service overseas in major conflicts culminating in the massive commitment to the war of 1914-18. There were camps at many places along the line, among the biggest being at Kinmel Bay and Conwy Morfa. The latter place had its own small station on the main line. But when war came it was not only the troops carried by the railway to those camps who went to war but also many of the railway staff themselves. The book includes stories of those who left the railway and the sacrifices they made. Among these, none is starker than the fate of two members of the Cooil family of Bangor. This family occupied a house overlooking Bangor station and two sons followed their father into working on the railway. Sadly, both died in the conflict, with one succumbing on the very last day of the war – 11 November 1918. They and others from the Bangor Railway Institute who died are commemorated on a plaque that was moved from a local church to Bangor station in 2020.

The role of the line in the Second World War was less dramatic but just as essential. North Wales was chosen as a centre for important civilian and military functions because it was mostly beyond the reach of the Luftwaffe – although a crew member on a railway ferry ship was killed by an enemy aircraft in 1940. There were important civil service functions carried out in north Wales such as by the Ministry of Food at Colwyn Bay where accessibility by rail was essential.

After 1945 the line from Chester to Holyhead was rather less involved in military matters as it turned to local needs and tourism before declining as people switched from the railway to cars. The book charts this change and the slow recovery that was suddenly halted by the COVID 19 pandemic that affected all railway travel. A more specific challenge to the Holyhead line is that posed by climate change – also topical at present – with much of the line potentially affected by rising sea levels. That challenge is also covered in the book – but that is another story!

Phil Lloyd

November 2021

The Chester and Holyhead Railway is available to order here.