The Thames – River of Death

Guest post from author M.J. Trow.

Twenty bridges from Tower to Kew –

(Twenty bridges or twenty-two) –

Wanted to know what the River knew.

For they were young, and the Thames was old

And this is the tale that the River told …

When Rudyard Kipling wrote about London’s river he was covering thousands of years of history, most of it upbeat and all of it fascinating. But the Thames has a dark side. Its strange eddies and cross-currents mean that the water plays tricks with floating objects; its mud hides a multitude of sins.

Between 1873 and 1888, the dismembered body parts of at least eight women were found along the Thames, floating in the water and washed up on the foreshore and nobody has ever been held accountable for their murders. From Hammersmith in the west to Rainham in the east, arms, legs and trunks were found at various intervals which proved an insoluble problem for the Metropolitan police charged with hunting a killer.

Whoever the Thames torso murderer was, he has a very strong claim to being the world’s first serial killer in the sense that we now understand it. Unfortunately, as the last torso victim was discovered, not in the river but under the railway arches at Pinchin Street in the East End, the Whitechapel murderer was already on the streets and no careful, secretive killer could compare with Fleet Street’s Jack the Ripper. At least two recent ‘true crime’ books have asserted with confidence that the Torso killer was Jack, completely ignoring the totally different MO involved. Contrary to crime fiction, serial killers do not change their habits to taunt the police or as the weather changes, but stick to what works for them. Jack was a ‘blitz’ killer, hitting his targets in the open and leaving their bodies, mutilated, in the street. The Torso killer operated in secret, almost certainly inside, dismembered his victims with almost surgical skill and was careful to remove the heads (never found) which made identification next to impossible.

But the Thames was used to bodies. The famous Battersea shield, discovered in 1857, was almost certainly an offering to Celtic gods – and human sacrifices were part of that process. The river was – and still is – a magnet for suicides. Much of the work of the ‘Bluebottles’, the Thames River Police, was fishing corpses out of the water. As the poet Shelley said to a friend, the Thames ‘runs with blood and bones of a thousand heroes and villains and no doubt the water is sour with tainting.’ At least 300 skulls have been found in the river’s mud, from the Neolithic to the Iron Age period.

Charles Dickens wrote in 1860, ‘The river had an awful look, the buildings on the banks muffled in black shrouds and the reflected light seemed to originate deep in the water, as if the spectres [of the dead] were holding them to show where they went down.’

Accidental deaths were common too. In 1647, sixty people died when the weir at Goring in Berkshire sank their boat. On 3 September 1878 (while the Thames torso killer was at large) nearly 700 died when the Princess Alice pleasure boat collided with a steam-collier, the Bywell Castle.

But, again and again, we focus on murder. In 1012, during a renewed Viking attack on England, Aelfeah, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was beaten to death with ox bones and an axe. His body was thrown into the river at Greenwich, where Nicholas Hawksmoor’s church now stands. Arguably, the most famous victims of the river were the princes in the Tower, Edward V and his brother Richard, who were almost certainly murdered in the summer of 1483. The reason the bodies were never found is that they were probably taken from the Tower via Henry III’s water-gate and dumped, suitably weighted, in the stretch of the Thames called, appropriately, the Black Deeps. And, traditionally, the heads of traitors, rebels and renegades, from William Wallace, the Scottish leader, to William Laud, adviser to Charles I, were placed on spikes on Tower Bridge, to be consigned to the river once the crows had finished with them.

At the western end of London’s river, Tyburn was the place of execution for countless felons on the scaffold known as the Triple Tree; their bodies hit the river. So did those beheaded at Smithfield, further east. Execution Dock ran beside the entrance to St Katherine’s Dock, one of the biggest in the Pool of London. Criminals, especially smugglers and pirates, were hanged nearby, their bodies coated in tar and tied in chains to bob with the tide. The place names along the river bear testimony to all this – Dead Man’s Steps at Wapping, Dead Man’s Island in the estuary and, hidden in the uprights of Tower Bridge, a small door that leads to a temporary hiding place for suicides – Dead Man’s Hole.

Dredgers were the men employed to fish bodies out of the water. By the 1890s, they were paid five shillings for each corpse.

One of the most bizarre incidents of river deaths occurred in 1568 when a Jesuit priest, George Napier, was hanged, drawn and quartered at Oxford. His body was dumped in the Thames and by the time it had reached Sandford, three miles downstream, it had, gullible eyewitnesses attested, become whole again.

The eight victims of the Torso killer would never be whole. Their body parts were examined, by doctors and the police and even ghoulish members of the public. But their murderer was never found. This book, perhaps, comes closest to identifying him.

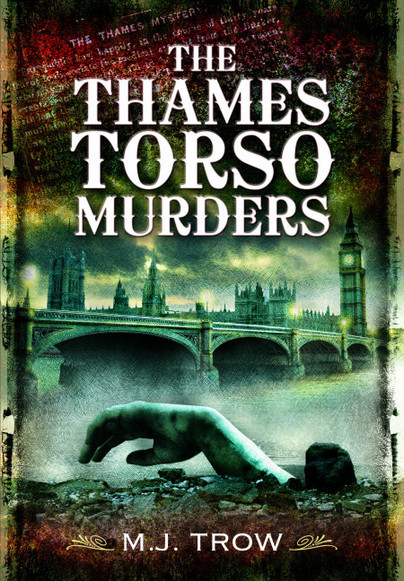

The Thames Torso Murders is available to order here.