Author Guest Post: Steve R. Dunn

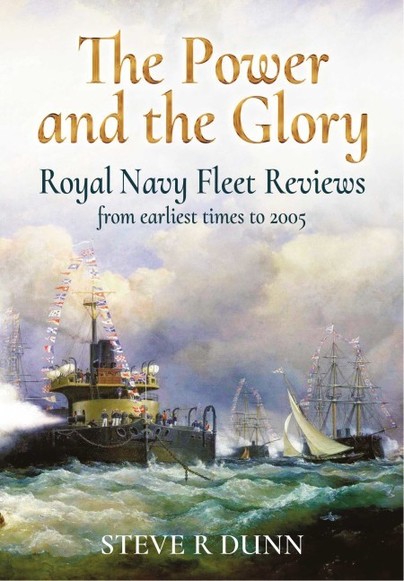

The Power and the Glory; Royal Navy Fleet Reviews From Earliest Times To 2005

In November 2020, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that he wants to make the UK the ‘foremost naval power in Europe’ as part of a multi-billion pound boost to defence spending. The PM vowed to ‘restore Britain’s position as the foremost naval power in Europe’. He added: ‘If there was one policy which strengthens the UK in every possible sense, it is building more ships for the Royal Navy.’

Politicians have been known to lie; but as a statement of intent, it is welcome. However, there is a long way to go before the Royal Navy is restored to its glorious prime. Recent decades have seen the navy go through a long period of almost terminal decline, which is perhaps reflected in the fact that there have been no royal reviews since 2005. When one considers that the Royal Navy was once the main pillar of British power, respected and revered across the world, it is disheartening that there has been so little investment over an extended period.

Think of, for example Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Royal Fleet Review of 1897 when 165 British warships assembled in five rows. Two lines comprised fifty-nine battleships and cruisers. There were thirty-eight third class cruisers and gunboats in another column, then a line of forty-eight destroyers and gunboats and another rank of twenty torpedo boats. And this was done without stripping ships from foreign stations, for the Royal Navy boasted 451 ships in total (not counting torpedo boats) of which 212 were in active commission.

Or reflect on the Royal Review before King George V in July 1914 when over 200 vessels participated, including twenty-four Dreadnoughts and battlecruisers, twenty-five pre-Dreadnoughts and eighteen large cruisers. They formed twelve lines stretching from the Isle of Wight to Portsmouth. Between 70,000 and 80,000 Royal Navy personnel were present at various times in the largest fleet ever assembled in British waters.

Britain has always needed a strong navy, for Britain was built on trade and the Royal Navy kept open the trade routes by which commerce flowed into and out of the country, whilst protecting the strands of empire, which grew as a result of the search for business across the world.

The review of their fleet by successive monarchs was a statement of the importance of the navy both in the protection of trade and the defence of the Islands of Britain. When in 1801, during the French revolutionary wars, ‘Grim’ John Jervis told the Board of Admiralty ‘I do not say, my Lords, that the French will not come, I say only they will not come by sea’, it was a statement of ultimate confidence in the strength of the navy, a strength recognised at the end of the wars, somewhat prematurely, by the Royal Fleet Review of 1814. Such a statement could not be made today.

The Power and the Glory surveys Royal Fleet Reviews from 1346 to 2005. The narrative tells of political manoeuvring, technological change and of the many naval characters involved. The book examines the stories of the ships involved and their often precipitous decline from fame to scrapyard. And it is a celebration of the Royal Navy’s presence in British history.

Available here.