DEADLY HORIZON: A short story by Murray Rowlands

An Introduction:

It is more than 80 years since the battle of Britain was fought over the skies of Morley and the whole of the South of England.

Morley has a link to these events. A former Vice Principal Denis Richards wrote an authoritative book about “The Few” and the life and death battle taking place in British skies in July, August and September 1940. There is another link between New Zealand and Morley. The daughter of The Agent General for New Zealand William Pember Reeves, Maude Blanco White, was Principal of Morley in the 1930s. Her other claim to fame was having been one of H.G.Well’s mistresses.

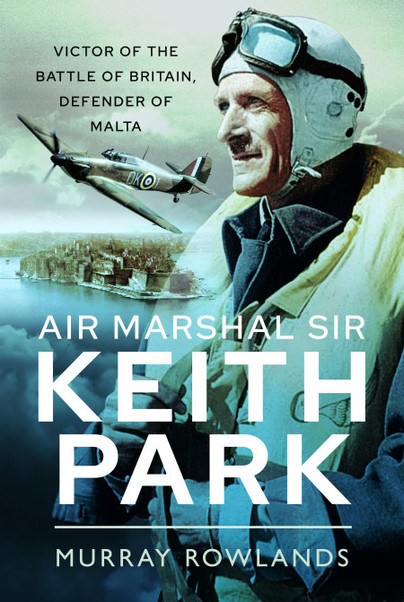

I have just written a new biography of Air Marshal Keith Park a legend who is widely regarded as the principal architect of Fighter Command’s victory in 1940. My association with Morley was as a Director of Humanities.

Murray Rowlands

DEADLY HORIZON

It was a comment in our local paper The Christchurch Press that put the idea of going to England and joining Fighter Command in the Royal Airforce in my mind. I had been spending money I really could not afford from working as a plasterer first on flying lessons and then on regular flights Saturday and Sunday at Wigram airport. I would cycle across from Kiapoi to Wigram airport when there always seemed to be a head wind going there and coming back although the roads on Canterbury Plains are as flat as a pancake. In my tool bag was my spirit level always showing a level horizon. Not even the change from the turmoil behind the north-west arch over the Southern Alps on the morning to the cruel barbs of the south west winds from the Antarctic could alter the vast tussock covered flatness of this horizon

When I pointed out the advertisement to my mother she was very upset. “Colin. Why do you want to do that? It is dangerous enough going up all the time at Wigram in those Tiger Moths without going up and fighting in them. I read about all those boys being killed over there. If you have to go wait until they call you up.”

But I just could not get rid of the challenge of being part of an opposition to the German fascists I had read about in my union journal that might incorporate the flying I loved. I now had to work out how could get to England and how I could afford it. One of my mates Alec who was not really settled with our Company Fletchers had talked about jobs going as purser on some of the boats coming into Lyttleton Harbour. On a late summer day in 1939 I caught the train at Opawa to Lyttleton and found my way to one of the shipping offices on the quayside.

“Not another one,” said the bloke in the office. “All you young ones can think of is getting out of the country to see the wide world.” But when I explained that I was a qualified pilot and wanted to get to England to protect the old country against the German fascists his attitude changed. He went into his office and came back with a piece of paper.

“I see the Ranagitata is due here in a couple of weeks. You can bet there’s some in the crew who jump ship and go for the wider horizons here. I’m not promising anything but come back then and there may be something for you.”

My luck was in. Two weeks later when the Ranagitata was birthed at Lyttleton there was a vacancy for a bursar on board.

“I’m relying on you to give those fascists hell,” the shipping clerk said after I had finished signing all the papers.

“Don’t keep going on, Doreen,” said my father in response to my mother who kept arguing and complaining about my imminent departure. “He wants new horizons. There are only flat ones in New Zealand. Let him go.”

The eyebrows of my boss at Fletchers went up when I said I was leaving. It was soon after the depression and any job was regarded as a nugget of gold.

“A rolling stone gathers no moss,” he said. “But good luck.”

The journey to England offered so many horizons. Two days in Sydney opened my eyes to how small Christchurch really was. On board it was as if stalking our thoughts there was the Omni-presence of the German threat either above or below the waves. For this reason there was blackout at night and deviations on receipt of intelligence of German presence in the ocean before us.

I think of Colombo with the violent gold of its sunsets as opening my horizon to a tropical sunset. Several of the other bursars tried to persuade me to go to parts of Colombo where they said some of the local girls could easily be picked up. Instead I went on an excursion in Colombo with Julia an English girl returning to England with her father. During the voyage we became quite close as far as my job would let me. I suppose this was another of my horizons because Julia and I arranged to meet in England.

As a collector of horizons I have to say London was a disappointment. A thick fog closed around me even thicker than the ones around the Avon in Christchurch. No horizons were in sight until having signed up with the Fighter Command I was posted to the de Havilland flying school at Hatfield and then on to Hornchurch. Even here it seems that the eternal spread of London was present conspiring to ignore all horizons.

I found another horizon when I was invited to Julia’s family home in Lambeth near the Thames. Her father is a Labour councillor and was even Mayor several years previously. Julia has no interest in going back to New Zealand and her horizon she spoke endlessly about is a place called Newquay in Cornwall. I was disappointed to discover this and rather went off her. Was I getting homesick for my locations in Christchurch and the plains?

Finally I qualified at Hatfield, received a merit grade for my firing and was posted to Biggin Hill. I arrived there just after the first of the many raids and a horizon is thick with smoke from bombed hangers. I am told in mess that there is a crisis because of a shortage of pilots and I will be flying the next day. Almost immediately I was ushered into a briefing room where Wing Commander Gray looks me over and starts quizzing me. He does not seem to accept what I tell him and ushers me out to a nearby Spitfire and perfunctorily tells me to take it up and do a circuit of the airfield. I tried to tell him that my experience had been more in Hurricanes but he insists.

I manage the take-off well and accomplish a circuit of Biggin Hill. Down below I saw a very tall officer who waves me down. I had to change hands on the control panel to operate the landing gear and my left hand produced a wobble in the aircraft causing it to clip some trees near the airfield. I felt something drop from the rear of the aircraft but despite this I managed a landing.

I opened the cockpit only to be confronted by the tall officer who seemed extremely angry.

“What I have witnessed was the worst piece of flying I’ve ever seen,” he shouted. ” It was if your training was of no use at all to you.”

“It’s the first time I’ve flown a Spitfire,” I blurted out. ”I’ve never had any trouble in a Hurricane.”

Then he seemed to calm down and looked at his watch.

“You’re from New Zealand aren’t you? Have to make a start some way I suppose. I’ll see you in what’s left of the mess at five o’clock.”

With that he strode off.

“Who was that?” I asked.

“You don’t know? That was Air Marshal Keith Park your ultimate commander. Young man you’re in deep trouble. You may be lucky though. He’s a fellow Kiwi.”

Fearing the worst later I approached Park in the mess who had beckoned me over.

“Despite everything there’s still some beer on tap. You can buy me one.” He looked at me intently. You know I’ve got two sons not much younger than you.”

I duly returned with two beers.

“When’s your first sortie?”

“I’m down for tomorrow,” I replied.

“I happen to know that aircraft. It has always suffered from a wobble which is disastrous to new chums. It’s a hard lesson and they were wrong to give an aircraft like that if your experience was in Hurricanes. It’s bad practice to give new pilots aircraft they’re unfamiliar with to fly.”

He then bought me a beer and we talked about New Zealand and Park spoke about how he missed being there. We were then joined by two other New Zealand pilots who I learned were Colin Gray and Alan Deere.

“Hope you’re not being too hard on the young man, Sir,” said Deere.

“Bit hard on him to expect him to make a switch from a Hurricane to a Spitfire,” Park said admonishing Gray. Park looked at his watch. “I must go. Come outside and watch how to take off without disturbing neighbouring trees”

I watched him climb into his plane OK1, taxi and very smoothly lift into the horizon of a peerless autumn sky.

“The weather’s too good. The bastards will be back tomorrow,” said Al Deere returning to the bar in the mess.

It was impossible to sleep that night. It was not apprehension at last at being able to put into practice what I had travelled 12,000 miles to do. For all those hours of sleeplessness my horizon at the end of my bunk bed was my suitcase. In it my mother had carefully packed all she thought I needed to travel across the world together with what I had been issued with by the RAF. Breakfast turned out to be better than at the training centres. I commented favourably to Al Deere who came to sit by me.

“I always think the grubs better here because they are fattening us up to be lambs for the slaughter,” he laughed. “Listen when we go up Gray wants you to follow me as it’s your first time.”

The alert bell sounded at 10.30 and we ran to our aircraft where the ground crew were waiting.

“Good luck,” the ground crew member said by my Spitfire. “I hope you have better luck with her this time.”

Once in the air I manoeuvred alongside Deere’s aircraft and he gave me thumbs up. Within ten minutes on the horizon I saw what seemed to be a never ending line of enemy aircraft. Deere waved me towards what I now realised were scores of Dornier Bombers. He beckoned upwards and I climbed to be above the leading aircraft. Suddenly I was aware I was on my own. Almost instinctively I set myself behind one till he dominated my horizon. It suddenly occurred to me that it would be like shooting rabbits down the headlights of our car in New Zealand. In seconds a plume of smoke had burst from the Dornier. In that instant I saw Deere gesturing desperately at me and pointing behind me. I pushed the stick to dive too late. My new horizon inside my cockpit was a profusion of yellow and orange tongues like a giant furnace. In my nose was the smell of burning flesh before oblivion in the turmoil of the golden oblivion.

Al Deere was given the job of collecting the new pilot’s possessions that afternoon. He lay on his bunk for several minutes staring at a horizon of a single suitcase and tears streaming down his face.

If you have enjoyed this short story, you can read more from Murray Rowlands here.