Children at Sea: Lives Shaped by the Waves by Vyvyen Brendon

During the six years I spent on this book I never ceased to enjoy delving into the evidence of lives shaped by early sea voyages. In March 2020 the pandemic shut down all the wonderful libraries, record offices, museums and art galleries I visited but I hope that researchers like me will soon be able to view their rich collections again, guided by their dedicated volunteer and professional staff. Here are some glimpses of the delights such investigations gave me.

1 Reading other people’s letters and journals

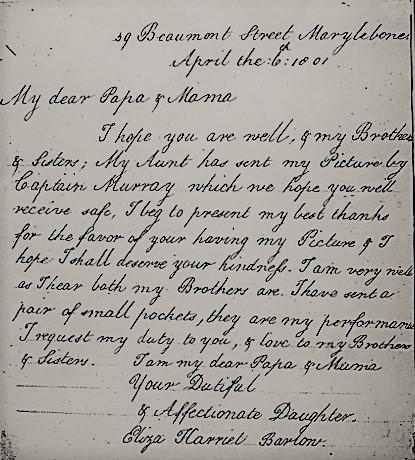

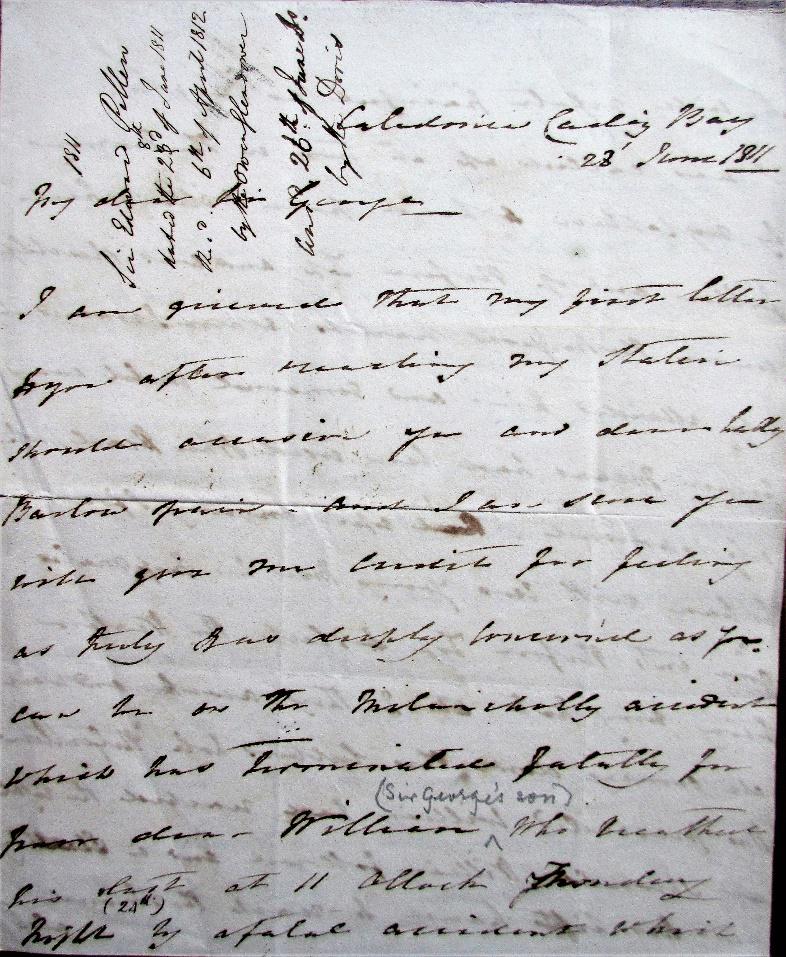

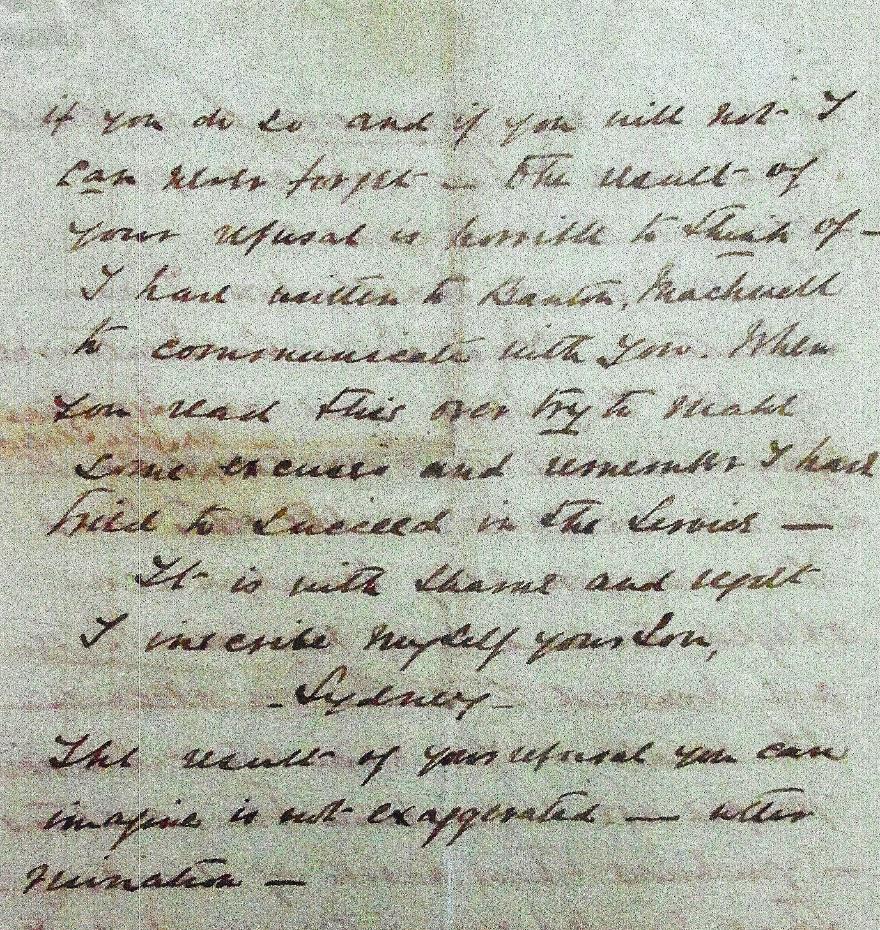

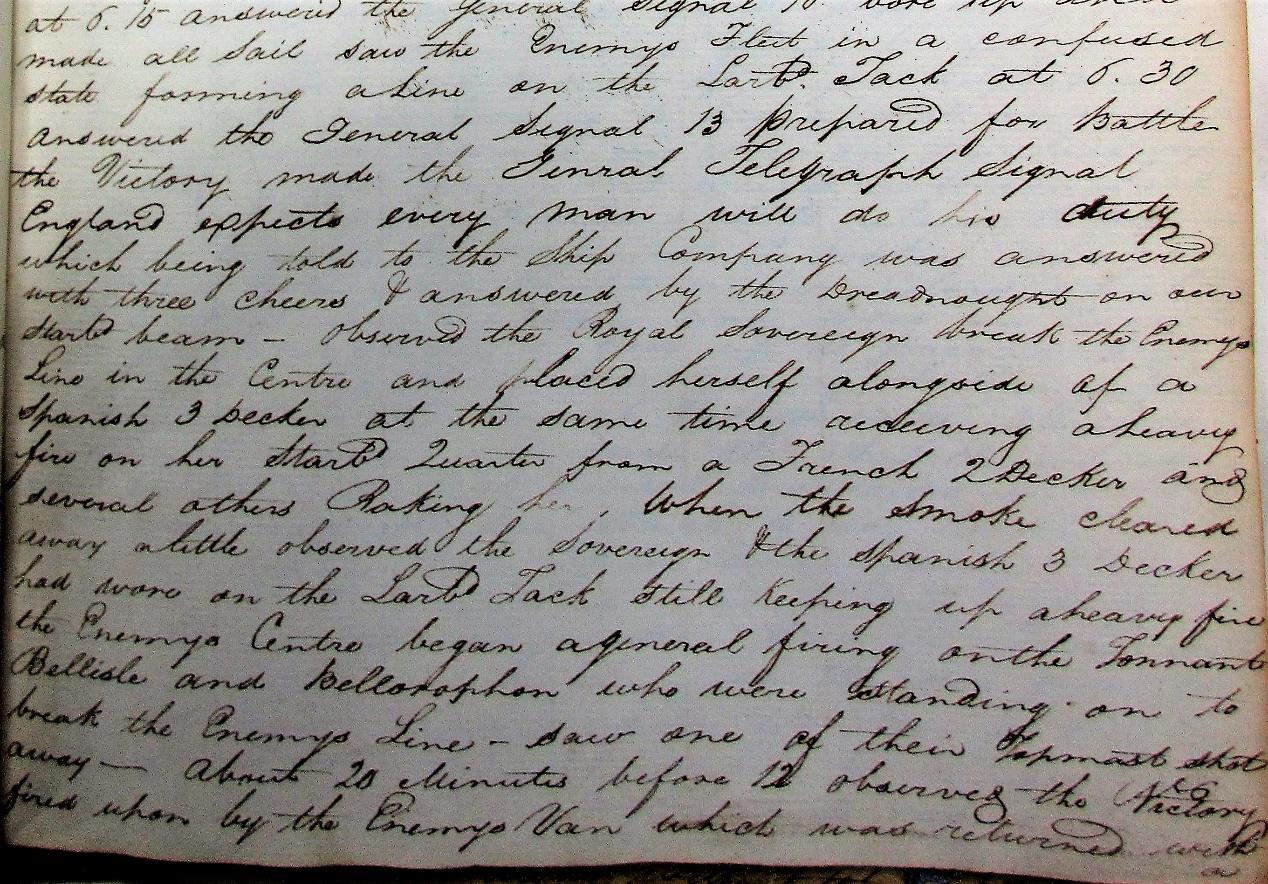

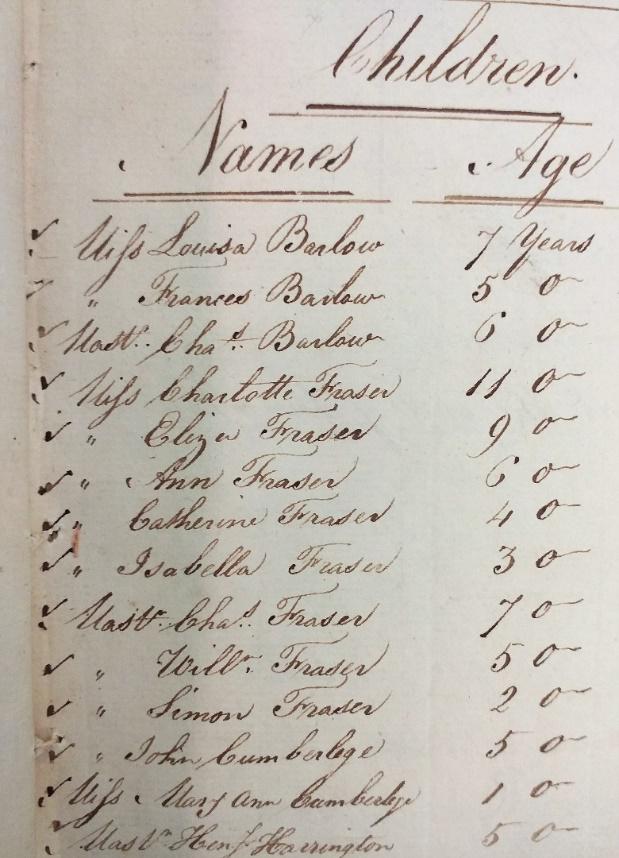

When I first explored the huge Barlow archive in the India Office Library for Children of the Raj the fragile letters themselves could still be handled. What a privilege it was to read words penned 200 years ago and despatched on sailing ships for a six-month journey to their anxious recipients. It wasn’t quite so exciting to consult the correspondence a few years later after it had been put on microfilm, but I was lucky enough to be lent some important original letters still held by a descendant of the family, Anthony Barlow. Another generous loan was from Bridget Somekh, who entrusted me with Othnel Mawdesley’s journal, inherited from an ancestor. It was amazing to be able to read this precious document in my own house before suggesting that it should be donated to the National Maritime Museum. I was less lucky with Sydney Dickens, most of whose letters ended up on his father’s bonfire of correspondence at Gad’s Hill. One which has been conserved, at the Dickens House Museum in Doughty Street, heartbreakingly announces the young man’s ‘utter ruination’.

2 Consulting official records

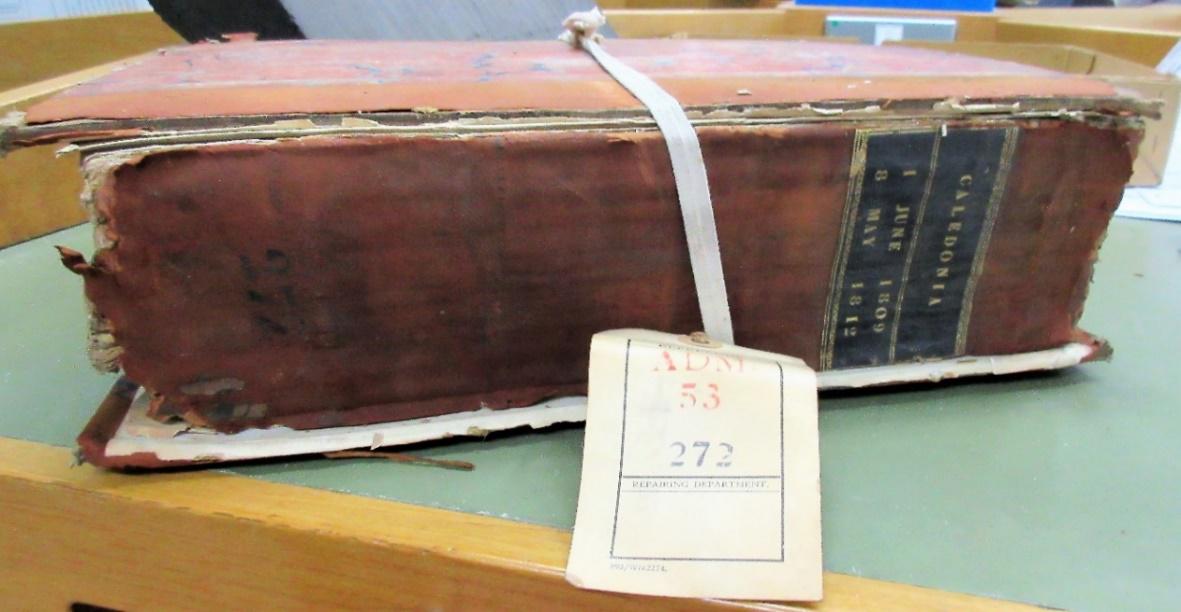

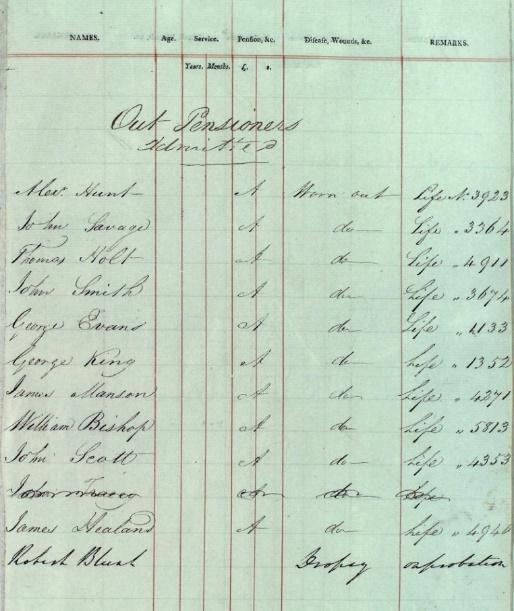

These are more fun than they sound and vital for authenticating personal accounts. The most extraordinary documents I consulted were ships’ log books housed in the National Archives at Kew. From the hand-written entries in these huge sea-battered, worm-eaten volumes I was able to track down, for example, the story of William Barlow’s death on board the Caledonia, the role of George King’s ship in the Battle of Trafalgar and the presence of seven-year-old Charles Barlow on the Surrey, an East Indiaman sailing from Calcutta to London. But sometimes the paper trail ran out, as nearly happened in the case of Barnardo’s children, whose files are now accessible only to direct descendants. One of these came to my rescue: from Canada Chris Beldan generously sent me copies of documents and photographs relating to his grandmother, Ada Southwell.

3 Online Searches

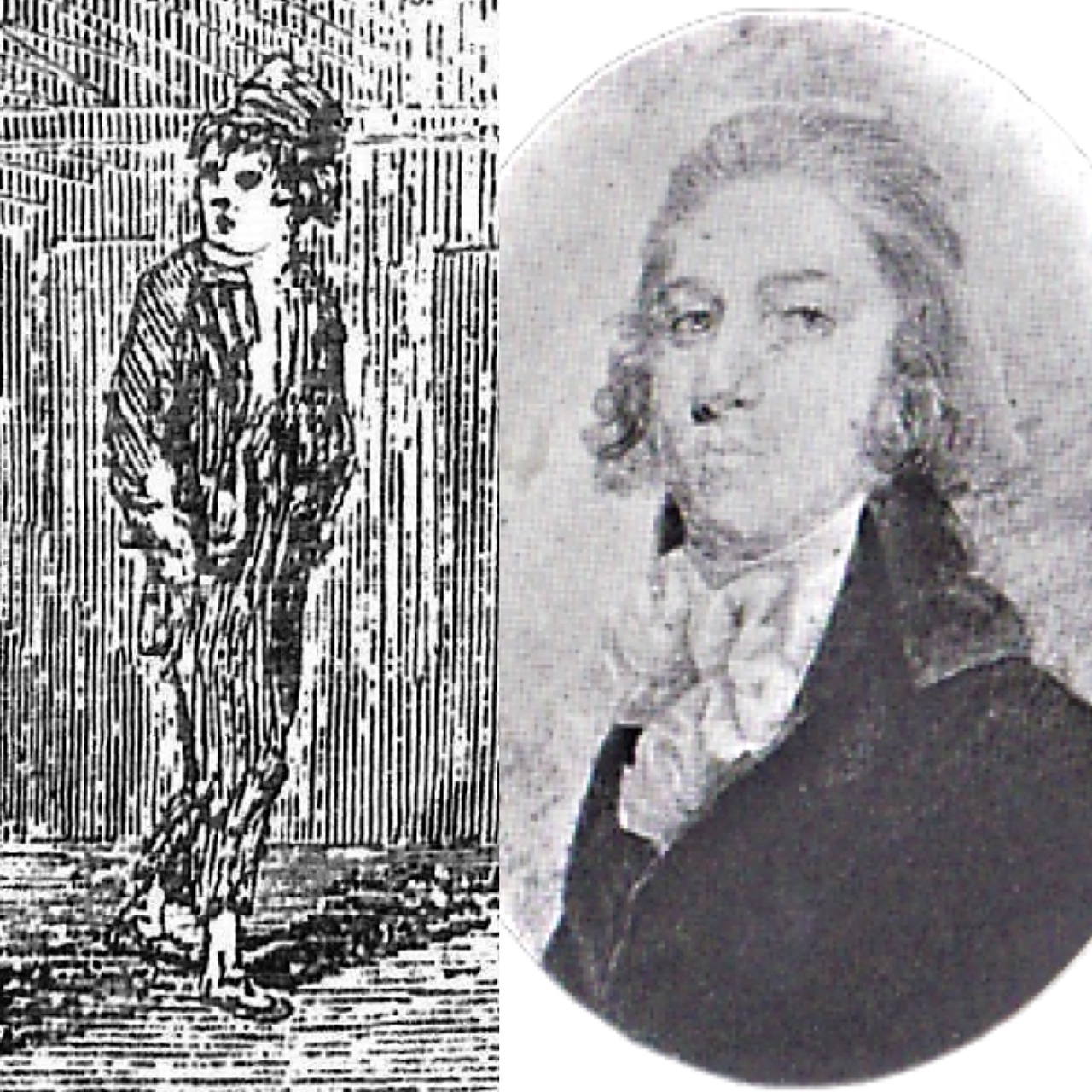

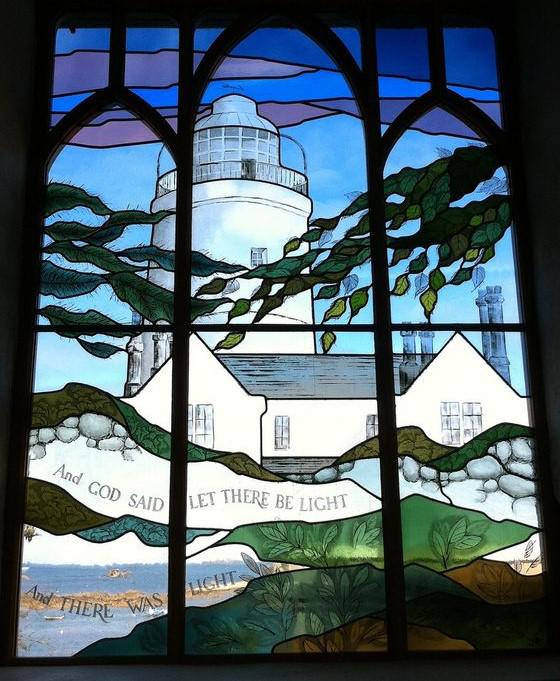

Tedious though surfing the internet may be, it can yield vivid personal details. Websites enabled me, for example, to quote the cheeky words used by young lads defending themselves at Old Bailey trials and the patronising comments of officers such as Marine Lieutenant Ralph Clark guarding them on the first transportation fleet. On the Greenwich Hospital site George King appears among a group of men admitted in 1832 on the grounds that they were ‘worn out’ – and yet the old salt was recorded in the 1851 Census as a married man living in a nearby street, six years before his death back in the hospital. I could only guess at what lay behind his changing fortunes. Sometimes great finds turn up by chance. I discovered that since my visit to St Agnes the islanders had raised enough money to install a stunning new window in the church depicting the lighthouse kept by my great-great grandfather.

4 Exploring museums and galleries

It’s in such places that one is most often transported back into the past. I had several such experiences while doing research into children at sea. In Truro’s Royal Cornwall Museum I was shown its treasured watercolour depicting the former slave Joseph Emidy leading a group of local musicians, here reproduced in colour as it could not be in the book. At the Docklands Museum I walked through its moving reconstruction of the part of east London once known as Sailortown, featuring the Three Mariners pub as well as a chandler’s shop, animal emporium and sailors’ lodging house. And when two of my grandchildren dressed up in realistic costumes at the Foundling Museum they were transformed into waifs before my eyes.

5 Seeking sailors’ haunts

It’s always thrilling to visit the places in which one’s characters lived and worked. I could sense the presence of my great-great grandfather at St Agnes Lighthouse; of Joseph Emidy at the Royal Opera House in Lisbon and the Assembly Rooms in Truro; of George King and Sydney Dickens at Chatham Dockyard. But for me simply gazing at the waves, especially those that beat upon the rocky shores of north Cornwall, will always conjure up visions of the children whose lives they shaped.

…………………………………………………………………………

You can order a copy of Children at Sea here.