Sea Battles That Changed the World – Phil Carradice

Almost everyone knows about the great land battles of history – Hastings, Waterloo, Stalingrad, Gettysburg and so on. But strangely – and perhaps disconcertingly for a sea faring nation – not many British people know much about the important sea battles of history. They are battles that did literally change the world.

One of the earliest but most significant was the Battle of Salamis which took place in 480BC. Victory for the Athenian Navy prevented the Persian fleet of King Xerxes linking up with his formidable army – already victorious in the Pass of Thermopylae – to form an unbreakable force that would have conquered Greece and then marched on into Europe. If that had happened European history, culture and lifestyles would be very different from the way they appear today.

The Athenian Admiral Themistocles was outnumbered by the Persians but superior tactics in the narrow seas around the island of Salamis enabled him to destroy the invaders. As a result Xerxes withdrew his forces, the Second Persian War came to an end and the glory that was ancient Greece was allowed to grow and develop.

A not too dissimilar action was fought in the Gulf of Corinth in 1571. Known as the Battle of Lepanto, it was a hugely significant victory for the navy of the Holy League, a Consortium of Catholic states located around the Mediterranean. The enemy – the rampaging forces of the Ottoman Empire. Without this victory the Turks would undoubtedly have continued their march westwards. Rome, Vienna, Paris – they could well have fallen to the Ottomans.

Lepanto, the last major all-galley action in the Mediterranean, was a crushing defeat for the Turks, a major victory for the Christian nations of the west. The Turks lost not only most of their ships but many experienced sailors and huge amounts of ammunition and weaponry. It was a battle that stopped the Turks in their tracks and really did change the course of history.

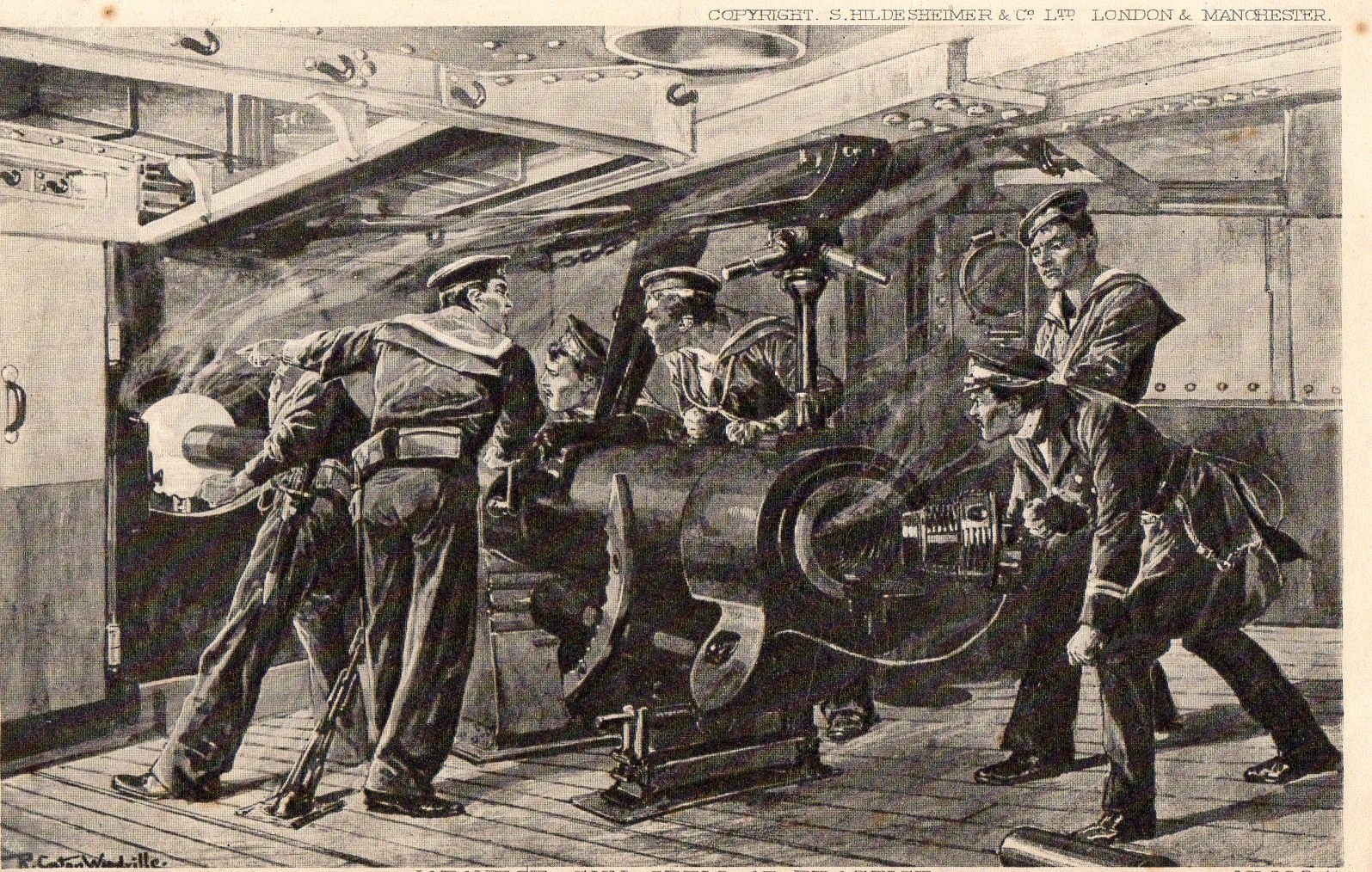

Trafalgar, of course, is a battle that most people know at least something about, even if it’s only Nelson’s supposed final words as he lay dying – ‘Kiss me Hardy.’ The battle in October 1805 revolutionized naval tactics with Nelson refusing to sail parallel to the French/Spanish fleet and engaging merely in a mutually devastating series of broadsides.

Instead he sailed directly at the enemy, smashed through their line, crossing the T as it is now known and captured or sank 22 of the French and Spanish ships. Compared to French/Spanish losses British casualties were minimal – 480 dead compared to over 4000 of the enemy.

Victory at Trafalgar ended Napoleon’s hopes of invading Britain. He turned his attention away from what he deemed a ‘nation of shopkeepers’ and looked eastwards, to Austria, Prussia and Russia. Eventually, the snows of a Russian winter finished what Nelson had begun in the waters off Cape Trafalgar. Britain, thanks to Nelson’s victory, went on to create the greatest empire the world had ever seen, an empire fuelled and protected by the Royal Navy.

Come forward now one hundred years, to May 1905. After sailing the Russian Baltic Fleet for 18,000 nautical miles around the world, Admiral Rozhestvensky met humiliating defeat at the hands of the Japanese sailor they called ‘the Nelson of the east,’ Admiral Togo. The Battle of Tsushima took place in the waters between Korea and southern Japan and apart from some brief encounters during the night, lasted barely an afternoon.

At the end of the battle the Russians had lost six modern battleships, fifteen other vessels and sustained over 10,000 sailors killed, wounded or captured. The Imperial Japanese Navy had lost three torpedo boats and taken casualties of just 117 dead. It was the first time any Asian nation had inflicted defeat on a European power.

Reasons for Rozhestvensky’s defeat are legion. Poor tactics, ships encumbered by months of weed on their hulls, accurate Japanese gunfire with newly developed shells – the list goes on and on.

The results of the battle were also extensive. Huge discontent amongst the Russian people, furious at the ignominy of defeat, was largely responsible for the 1905 Revolution. That rising was brutally put down by the Cossacks of the Romanov dynasty – put down but not extinguished and revolt against the Czar and his regime flared again in 1917. This time the revolution was successful.

Equally as notable, the Battle of Tsushima marked the start of Japan’s rise as a world power. Control of the Pacific was only one element of Japanese aggression in the early part of the twentieth century, aggression that had been fuelled by victory at Tsushima but which led, ultimately, to the country’s destruction in 1945.

If the attack on Pearl Harbour in November 1941 was proof of Japan’s militaristic intentions, defeat at the Battle of Midway just six months later was undoubtedly the start of the Empire’s decline.

Originally intended to eliminate the American Fleet, particularly the aircraft carriers that had been absent from Pearl Harbour, the Japanese operation failed badly. American cryptographers had broken the Japanese naval codes and what was intended as a trap for the US ships at Midway Atoll became, instead, a trap for the Japanese.

The battle, fought between two navies that never actually saw each other, was an aerial combat that lasted from 4 to 7 June 1942. It resulted in the Japanese losing four aircraft carriers to America’s one, 248 planes to America’s 150. More importantly, it marked the beginning of the end for the Japanese Empire and a conflict that had been brewing since Togo’s victory at Tsushima. It saw the end of the battleship as an offensive weapon and the advent of naval air power.

The battles mentioned here are just some of the great naval engagements that, in one way or another, have influenced history. There are many more – the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Jutland and the Coral Sea to name just three. Whether they are as significant as the ones mentioned above – well, that’s an entirely different topic.

Read more from Phil Carradice in Britain’s Last Invasion which is available to order here.