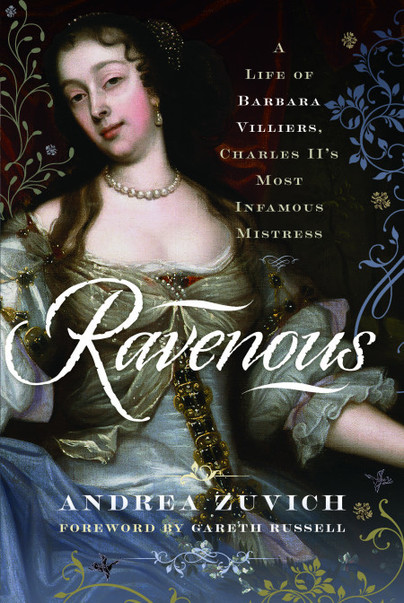

5 Things You Didn’t Know about Barbara Villiers, Charles II’s Most Infamous Mistress

Author guest post from Andrea Zuvich.

If you don’t already know who Barbara Villiers was, sit back and enjoy 5 facts about this incredible woman! She is best known for being King Charles II’s mistress for a decade – a time in which she held as much or greater power than his wife, Catherine of Braganza. Barbara was a larger-than-life character – her life couldn’t have been more dramatic: she rose from being a penniless aristocrat to a wealthy duchess, she had dozens of lovers, lived in sumptuous lodgings in London and Paris, and was a major Stuart-era fashionista. Barbara, who was known for terrible rages when crossed, is one of those historical figures who impacted many around her, inspiring artists, actors, playwrights, and more. Her legendary beauty (diminished only by our modern-day notions, perhaps) created a glamorous aura about her that continued long past her death in 1709. So powerful was this sensual appeal as was her hold upon the king, for so long, that she has never been forgotten. Her image has consistently been in print, too. Fanciful depictions of her have been found in 18th-century engravings and even in early 20th-century cigarette advertisements, such as this for Player’s Cigarettes:

She has been characterised in countless plays, films, and historical novels. Any study of the Restoration period in England (beginning in 1660), would not be complete without Barbara Villiers.

- She lost her father at a young age and knew poverty. Although Barbara’s parents came from wealthy, aristocratic families (her father was a Villiers and a St.John, and her mother, a Bayning), their finances were badly hit as a result of the English (or British) Civil War. During this bloody conflict, Barbara’s father, William Villiers, 2nd Lord Grandison, fought for King Charles I and lost his life several weeks after being shot in the leg during the Siege of Bristol in 1643, aged only 29. Barbara was not even three years old when she lost her father. This lack of a fatherly figure (despite getting a stepfather, Charles Villiers, when her mother remarried when Barbara was eight) is likely to have impacted her psychologically and financially. This may possibly also have led to her constant need to seek love and attention from men throughout her life. Although she remains synonymous with glamour and wealth, the war and her father’s death led to a very difficult financial situation for Barbara and her widowed mother, Mary. I believe it is likely that her formative years, in relative poverty, engrained in her a need, an obsession even, to acquire as much as possible and ensure her children would be financially safe. Her covetousness became well known as she possessed a strong drive to have the most ostentatious and luxurious clothing, jewellery, accessories, apartments – you name it, she had it. Less is more? Not for Barbara, more was more, and best.

- Her first love was not King Charles II. A few years before she even met King Charles, a young teenaged Barbara fell madly in love with Philip Stanhope, 2nd Earl of Chesterfield, a widower in his early twenties. Although he wasn’t particularly faithful to her (he was seeing other women at the same time), they nevertheless had a great deal in common and were highly suited to one another in terms of physical attraction, political allegiances, and in their characters. Theirs was an extremely passionate affair and in her letters to him from this time, Barbara clearly adored him and would (and likely did) anything for him. They would have made a very good match, were it not for the fact that Barbara still had no money. But did love conquer all for this couple? No. Chesterfield simply wouldn’t marry Barbara as she was too poor. If she had been wealthy, he’d certainly have married her. Distraught, the eighteen-year-old Barbara wed one of her many admirers, a young —and thoroughly decent—man named Roger Palmer. She very quickly regretted this marriage and carried on her relationship with Chesterfield. In time, Chesterfield eventually pursued and married the very wealthy and well-connected Elizabeth Butler, daughter of the Duke of Ormond: and had a miserable short-lived marriage, ending with Elizabeth’s death at the age of 25. There is some reason to suspect that Barbara’s first child, Anne, may have been fathered by Chesterfield and not Charles II.

- She’s not to blame for Nonsuch Palace. By the time Nonsuch Palace came into Barbara’s hands, it was over 100 years old, suffered through the turmoil of civil war, and was very dilapidated. We have reason to think that she considered living in the palace, but reality quickly proved this to be prohibitively expensive and Barbara had financial difficulties stemming from her love of luxury and her losses at the card tables. Although she had many flaws, enjoyed an extravagant lifestyle, was a gambler, and not a very good one, various legal documents attest that when it came to finances, she usually relied heavily upon the advice of others, usually men who were also her lovers. By this time, her losses and subsequent debts had put her in a financially vulnerable position. Therefore, the destruction of Nonsuch — for which Barbara has been blamed for centuries — must only be judged in the proper context. Yes, she sold the materials from an already-ruined palace to make money, but she did not have Nonsuch destroyed completely. After her death, her grandson, Charles, 2nd Duke of Grafton, carried out the remainder of the demolition. Whilst the thought of destroying a historical building is certainly abhorrent to most civilised amongst us, Barbara continues to be vilified for her part in Nonsuch’s destruction when it was something others did without shame. Oatlands Palace, another beautiful Tudor palace, was also destroyed in the Stuart period. It, too, was in a state of great dilapidation, but bought by Robert Turbridge during the Interregnum. Turbridge had Oatlands destroyed and its bricks and other materials sold twenty years before Barbara even had anything to do with Nonsuch.

- She worried she would be murdered. As a royal mistress, she was loved by some and really hated by others. Throughout her time as powerful mistress, she lived with the underlying fear that she could be murdered as her great uncle, George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, had been. He had been extremely powerful as a favourite of both King James I (IV of Scotland) and King Charles I, and widely despised. In 1628, he was stabbed to death in Portsmouth. Some decades after this grisly incident, Barbara would have very unpleasant and unsettling experiences of her own; some which could have been equally fatal. During a return journey from the Duchess of York’s home as she travelled via sedan chair in St James’s Park, three masked men suddenly set upon her and hurled obscene abuse at her. She was a whore, they shouted, and would end up like Jane Shore (Edward IV’s mistress). She doesn’t seem to have suffered any physical violence during this episode, but she could easily have been. It was a frightening experience and she was left truly disturbed. As quickly as they had sprung upon her, they left, and Barbara commanded her chair holders to take her to Whitehall Palace with the upmost speed. Running to Charles, a hysterical and terrified Barbara sought comfort in the king’s embrace. Some effort was made to apprehend the culprits, but no one could be positively identified.

- Her good health ran out in the end. Barbara enjoyed rude health for most of her life, and survived many pregnancies and births. She contracted smallpox in her late teens, which was often fatal or disfiguring. She, however, recovered quickly and was, amazingly, left unblemished. As she got into her fifties and sixties, however, her health began to deteriorate; exacerbated by physical abuse she endured at the hands of her second husband, Robert Fielding. In her last few years, Barbara’s once-powerful physical attributes had all but gone, and she, suffering from oedema and without any of the treatment possible today, likely died of heart failure. Ironic, in some respects, for a woman who pursued love all her life.

Ravenous is available to order here.