5 Facts about Women and Magna Carta

Author guest post from Sharon Bennett Connolly.

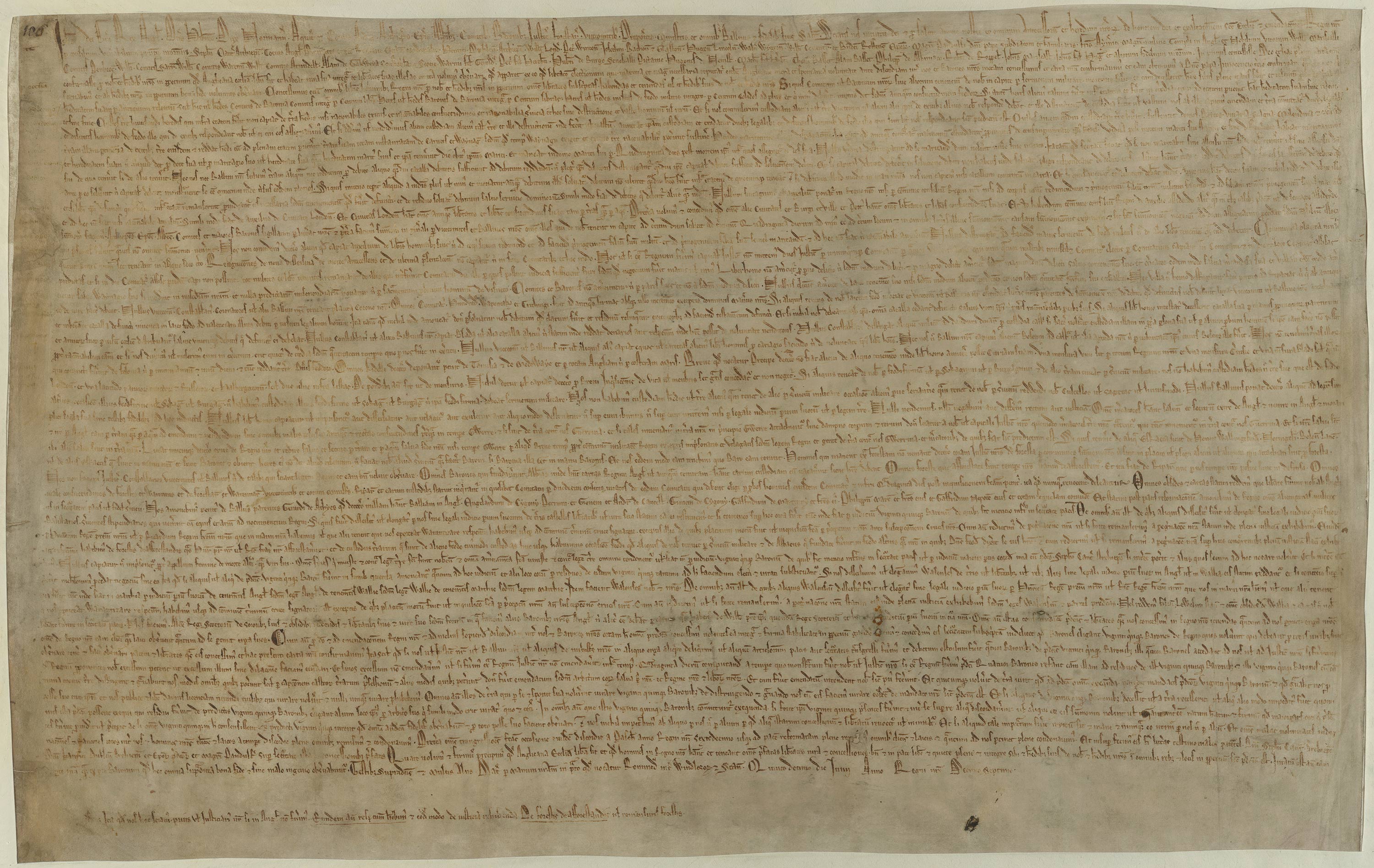

Magna Carta is probably the most significant charter in English history and, today, its importance extends beyond England’s shores, holding a special place in the constitutions of many countries around the world. Despite its age, Magna Carta’s iconic status is a more modern phenomena, seen in the influence it has had on nations and organisations throughout the world, such as the United States of America and the United Nations, who have used it as the basis for their own 1791 Bill of Rights and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, respectively.

Originally called the Charter of Liberties, it was renamed Magna Carta, or Great Charter, in 1217, when the Charter of the Forest (see Appendix C) was issued. Sealed (not signed) in the meadow at Runnymede in June 1215, the legacy of Magna Carta, down through the centuries, has enjoyed a much greater impact on history and the people of the world than it did at the time of its creation. As a peace treaty between rebellious barons and the infamous King John, it was an utter failure, thrown out almost before the wax seals had hardened, not worth the parchment it was written on.

The Magna Carta of 1215 reflects the needs and events of the time in which it was issued; an England on the brink of civil war, disaffected barons demanding redress, the Church and cities such as London looking for protection. It was not a charter that was intended to form the protection and legal rights of every man, woman and child in the land; though it has come to be seen as just that in subsequent centuries. Indeed, the common man does not get a mention, and of the sixty-three clauses, only eight of them mention women as a gender. Only one clause uses the word femina – woman – and that is a clause which restricts the rights and powers of a woman, rather than upholding them.

1. As queen, Isabelle d’Angoulême is mentioned in Clause 61, the security clause of Magna Carta: ‘…And if we or our justiciar, should we be out of the kingdom, do not redress the offence within forty days from the time it was brought to the notice of us or our justiciar, should we be out of the kingdom, the aforesaid four barons shall refer the case to the rest of the twenty-five barons and those twenty-five barons with the commune of all the land shall distrain and distress us in every way they can, namely by seizing castles, lands and possessions, and in such other ways as they can, saving our person and those of our queen and our children, until, in their judgement, amends have been made; and when it has been redressed they are to obey us as they did before…’

2. Other than Isabelle d’Angoulême, only 2 women can be positively identified in the text of Magna Carta. Though they are not named, the Scottish princesses, Isabella and Margaret appear in clause 59 as the ‘sisters’ of Alexander II, King of Scots: ‘We will treat Alexander, king of Scots, concerning the return of his sisters and hostages and his liberties and rights in the same manner in which we will act towards our other barons of England, unless it ought to be otherwise because of the charters which we have from William his father, formerly king of Scots; and this shall be determined by the judgement of his peers in our court.’

3. Magna Carta restricts the right of women to accuse others of murder. Clause 54 states: ‘No one shall be taken or imprisoned upon the appeal of a woman for the death of anyone except her husband.’ In a time when a man had the right to face his accuser in trial by combat to prove his innocence, this right would be automatically removed if his accuser was a woman; women were not allowed to use force of arms. A female accuser was seen as being able to circumvent the law, and therefore the law was open to abuse. It was merely that a woman may make a false accusation, rather that a woman may be manipulated by her menfolk to make an accusation, knowing that she would not be required to back it up by feat of arms. Whereas her husband, father or brother may have been challenged to do just that. Clause 54 was used on 5 July 1215, when King John ordered the release of Everard de Mildeston, an alleged murderer. Everard had been accused of the murder of her son, Richard, by Seina Chevel. The charge was therefore forbidden under the terms of Magna Carta, and the accused released.

4. The experiences of Loretta de Braose are believed to have inspired Clauses 7 and 8, which sought to protect the rights of widows. Clause 7 established that: ‘After her husband’s death, a widow shall have her marriage portion and her inheritance at once and without any hindrance; nor shall she pay anything for her dower, her marriage portion, or her inheritance which she and her husband held on the day of her husband’s death; and she may stay in her husband’s house for 40 days after his death, within which period her dower shall be assigned to her.’

5. The dreadful fate of Matilda de Braose, left to starve to death in John’s dungeons, is thought to have influenced clauses 39 and 40 of Magna Carta. Clause 39 states; ‘No man shall be taken, imprisoned, outlawed, banished or in any way destroyed, nor will we proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land.’ Clause 40 promised: ‘To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.’ Clause 39 could not prevent the perpetual imprisonment of women of royal blood, such as Eleanor of Brittany and Gwenllian of Wales. Their royal blood made them a focus for rebellion and opposition and therefore a threat to the throne and the stability of the kingdom.

6. Ela of Salisbury used clause 8 of Magna Carta to support her rejection of an unwelcome offer of marriage: ‘No widow is to be distrained to marry while she wishes to live without a husband.’

7. Isabel d’Aubigny famously invoked Magna Carta when Henry III commandeered land and rights that were rightly hers, proclaiming; ‘Where are the liberties of England, so often recorded, so often granted, and so often ransomed?’

Ok, so there were 7 facts about women and Magna Carta – instead of 5 – but I just couldn’t NOT include those last 2!

Author bio:

Sharon Bennett Connolly is the best-selling author of 4 non-fiction history books. Sharon is the author of Heroines of the Medieval World, Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest and Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England. Her fourth book, Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey, telling the story of the Warenne earls over 300 years and 8 generation, was released in May 2021. A member of the Royal Historical Society, Sharon has studied history academically and just for fun – and has even worked as a tour guide at historical sites. She writes the popular history blog, www.historytheinterestingbits.com. Sharon regularly gives talks on women’s history; she is a feature writer for All About History magazine and her TV work includes Australian Television’s ‘Who Do You Think You Are?‘

Links:

Ladies of Magna Carta is available from Pen and Sword and Amazon.

Defenders of the Norman Crown: Rise and Fall of the Warenne Earls of Surrey is available from Pen and Sword and Amazon.